Clinical Features and Prognosis of B-cell Lymphoma-associated Hemophagocytic Syndrome: A Retrospective Single Center Study

, Xudong Zhang1, Siyu Qian1, Zeyuan Wang1, Meng Dong1, Xiaojuan Zhang2, Xiaoguang Duan2, Yue Zhang1, Qing Wen1, Jingjing Ge1, Yaxin Lei1, Mingzhi Zhang1, Qingjiang Chen1, *

, Xudong Zhang1, Siyu Qian1, Zeyuan Wang1, Meng Dong1, Xiaojuan Zhang2, Xiaoguang Duan2, Yue Zhang1, Qing Wen1, Jingjing Ge1, Yaxin Lei1, Mingzhi Zhang1, Qingjiang Chen1, *- DOI

- 10.2991/icres.k.211129.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- B-cell lymphoma; hemophagocytic syndrome; clinical features; prognosis

- Abstract

Purpose: Current knowledge of Lymphoma Associated Hemophagocytic Syndrome (LAHS) mainly relies on T/NK-cell LAHS cases, while B-cell lymphoma associated hemophagocytic syndrome (B-LAHS) variant are rare. We aimed at identifying a single-center cohort of patients with B-LAHS to shed light on relevant clinical and laboratory features, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis.

Methods: The clinical data of 36 patients with B-LAHS, admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University in the time period ranging from January 2011 to May 2021 were analyzed retrospectively. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method and groups were compared using the log-rank test.

Results: The 36 patients included 17 males and 19 females with a median age of 53.5 years (range: 28–74 years). Among these, the most common histopathological type diagnosed was diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (69%). The initial symptoms included fever (100%), splenomegaly (97%), multicavity effusion (83%), abnormal liver function (58%), and jaundice (44%). Patients treated with dexamethasone only seemed to have an inferior prognosis compared to those treated with etoposide-involving regimens (χ2 = 20.037, p < 0.001). Patients received based on the Hemophagocytic Lymphohistocytosis (HLH)-2004 protocol combined with multidrug chemotherapy had a significantly improved Overall Survival (OS) compared to patients who only underwent treatment according to the HLH-2004 regimen (χ2 = 30.744, p < 0.001). The 2-week mortality rate was 13.9% and the 1-year OS rate was 19.4%. Compared with the median survival time of 34 patients without Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection, 97 days (range: 24–322 days), two patients with EBV infection died within 8 days.

Conclusion: B-LAHS is relatively rare and has a high early mortality rate, mostly in middle-aged and elderly patients. The HLH-2004 regimen combined with multidrug chemotherapy is a reasonable choice for the treatment of B-LAHS, and EBV infection may be used as a reference indicator of a poor prognosis.

- Copyright

- © 2021 First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University. Publishing services by Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

Secondary Hemophagocytic Syndrome (HPS), also known as Hemophagocytic Lymphohistocytosis (HLH), is a life-threatening syndrome caused by secondary overstimulation of the immune system, with a high mortality rate even after appropriate treatment. HLH is often triggered by malignancies, infections or autoimmune diseases with the Malignancy-Associated Hemophagocytic Syndrome (MAHS) accounting for the highest proportion of secondary HLH (about 48%), and Lymphoma Associated Hemophagocytic Syndrome (LAHS) being the most common [1–3]. Among the LAHS cases, T/NK-cell lymphoma is much more common than the rarely seen B-cell lymphoma [4]. B-cell LAHS (B-LAHS) is predominantly described in Asian populations but larger sets are rare. Early clinical manifestations of HLH are nonspecific, mostly manifesting in persistent fever, pancytopenia and hepatosplenomegaly with an aggressive disease progress [5]. Therefore, early diagnosis and immediate introduction of appropriate treatment are crucial for these patients.

A retrospective study of 36 B-LAHS cases, admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University within the time period ranging from January 2011 to May 2021, was conducted to investigate the clinical and laboratory features, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of B-LAHS, aiming at improving the understanding of B-LAHS and provide recommendations for an early treatment.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Patients

The case data of 36 inpatients with B-LAHS, initially diagnosed and treated at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University within the time period ranging from January 2011 to May 2021, were analyzed, including two cases in 2011, two cases in 2012, three cases in 2013, and one case in 2014, one case in 2015, two cases in 2016, one case in 2017, five cases in 2018, six cases in 2019, nine cases in 2020, and four cases in 2021. Pathomorphology and immunohistochemistry of lymph node or bone marrow biopsies confirmed B-cell lymphoma disease. All patients were pathologically diagnosed according to the classification guidelines of the World Health Organization 2016 [6] and HLH diagnosis was performed according to the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria [7].

2.2. Diagnosis of HLH

Hemophagocytic lymphohistocytosis is diagnosed when five of the following eight indicators are met. (1) fever: body temperature >38.5°C for more than 7 days; (2) splenomegaly; (3) cytopenia affecting ≥2 cell lines (hemoglobin <90 g/L; platelet count <100 × 109/L; neutrophil count <1.0 × 109/L); (4) hypertriglyceridemia (fasting triglycerides >3.0 mmol/L) and/or hypofibrinogenemia (<1.5 g/L); (5) hemophagocytosis in bone marrow, spleen, liver, or lymph nodes; (6) hyperferritinemia (>500 μg/L); (7) low or absent NK cell activity; (8) elevated level of sCD25 (soluble interleukin-2 receptor) >2400 U/mL.

2.3. Efficacy Assessment of Treatment and Follow-up of Patients

The treatment response was assessed according to Cheson et al. [8]. Overall Survival (OS) was defined as the time from the date of bone marrow aspiration to death due to any cause or latest follow-up. Patients were followed up until June 2021.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) software was used for statistical analyses. Categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage and skewed data was presented as median and interquartile range. Survival functions were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and the two groups were compared using the log-rank test. A probability of p < 0.05 was considered as being statistically significantly different.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Clinical Features

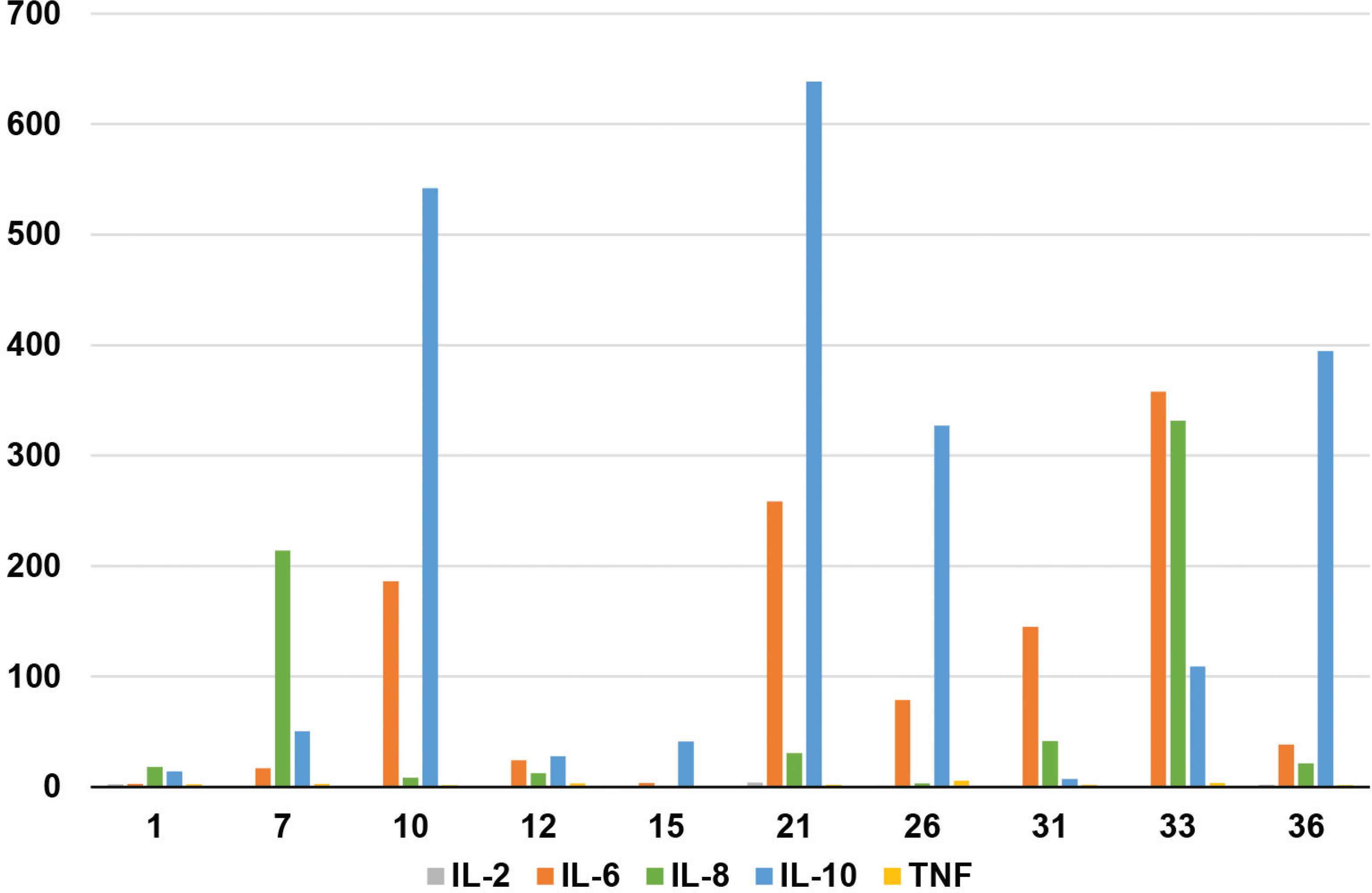

B-cell lymphoma associated hemophagocytic syndrome patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Of the 36 patients, 17 were males and 19 females, with a median age of 53.5 years (range: 28–74 years) and a duration of disease ranging from 3 days to more than 3 months. The most frequent B-LAHS type identified was a Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) in 69% of all cases. Of these, 92% of the patients were suffering from a Non-Germinal Center B-cell-like lymphoma (nonGCB). The other types included Marginal Zone B-cell Lymphoma (MZL) (6%), Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) (6%), Follicular Lymphoma (FL) (3%), and unclassified B-cell lymphoma (17%). The majority of the patients (86%) were classified into the Ann Arbor stage IV. The most common initial symptom was fever (100%) followed by splenomegaly (97%), multicavity effusion (83%), lymphadenopathy (72%), abnormal liver function (58%), and jaundice (44%) (total bilirubin above 34.2 μmol/L). 35 patients (97%) exhibited cytopenia and an elevated serum ferritin level with a median value of 2929.5 μg/L (range: 1675.3–10922.6) and 20 patients (55.6%) were diagnosed as having bone marrow hemophagocytosis. Ten patients showed elevated inflammatory factor levels such as of IL-10 (100%), IL-6 (80%) and IL-8 (70%). Specific clinical information is detailed in Figure 1. In addition, NK cell activity was determined in 14 patients of which 13 had a low NK cell activity and two patients displayed significantly high levels of sCD25 (140045 pg/ml, 18936 pg/ml, respectively) as detected by other hospitals.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 17 (47) |

| Female | 19 (53) |

| Age > 60 years | 16 (44) |

| B-cell lymphoma | |

| DLBCL | 25 (69) |

| MZL | 2 (6) |

| MCL | 2 (6) |

| FL | 1 (3) |

| Unclassified | 6 (17) |

| Previous lymphoma history | 6 (17) |

| Newly diagnosed lymphoma | 30 (83) |

| Ann Arbor stage III | 4 (11) |

| Ann Arbor stage IV | 31(86) |

| IPI score > 3 | 21 (58) |

| Bone marrow invasion | 29 (80) |

| Symptoms and signs | |

| Fever | 100 (100) |

| Splenomegaly | 35 (97) |

| Multicavity effusion | 30 (83) |

| Lymphadenectasis | 26 (72) |

| Hepatomegaly | 11(31) |

| Jaundice | 16 (44) |

| Laboratory data | |

| ANC < 1.5 × 109/L | 18 (50) |

| Hb < 90 g/L | 36 (100) |

| PLT < 100 × 109/L | 35 (97) |

| ALT > 40 U/L | 19 (53) |

| AST > 40 U/L | 18 (50) |

| TG > 3 mmol/L | 23 (64) |

| Ferritin ≥ 10000 μg/L | 10 (28) |

| FIB < 1.5 g/L | 16 (44) |

| LDH > 245 U/L | 33 (92) |

| β2-MG > 3 mg/L | 24 (67) |

| ALB < 30 g/L | 30 (83) |

| BM hemophagocytosis | 20 (56) |

| EBV-DNA copies > 103 | 2 (6) |

| Elevated CRP | 100 (100) |

| Elevated PCT | 100 (100) |

Unclassified, unclassified B-cell lymphoma; IPI, International Prognostic Index; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; Hb, hemoglobin; PLT, platelets; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; TG, triglyceride; FIB, fibrinogen; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; β2-MG, β2-microglobulin; ALB, Albumin; BM, bone marrow; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; CRP, C-reactive protein; PCT, Procalcitonin.

Clinical characteristics of 36 patients with B-LAHS

Levels of inflammatory factors in 10 patients with B-LAHS.

3.2. Infection

Two patients showed an Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection (EBV-DNA quantity was above 103 copies/ml). Blood culture revealed: one case of Klebsiella pneumoniae and one case of Escherichia coli; sputum culture displayed: one case of mixed infection of Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, one case of mixed infection of P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae, two cases showed A. baumannii and one case showed P. aeruginosa infection. Transairway biopsy revealed: one case of mixed infection of Mucor and Aspergillus as well as one case of Mucor infection. No pathogens were detected in the other patients and only inflammatory exudates were observed on pulmonary Computed Tomography (CT) images.

3.3. Diagnosis and Outcomes

All patients met the diagnostic criteria for B-LAHS. The diagnosis time for 36 patients ranged from 3 to 34 days with a median of 13 days. Thirty patients were newly diagnosed as lymphoma and six had a previous lymphoma history. Of 36 patients with B-cell LAHS, 12 patients faced rapid disease progression of HLH and died of severe bone marrow suppression, multiple organ failure, septic shock, and cerebral hemorrhage within a short time frame. A total of 24 patients were initially controlled for HLH, one of which was considered to have central lymphoma invasion and died of tumor progression, one patient died of out-of-hospital infection, three patients abandoned follow-up chemotherapy, and the remaining 19 transitioned to chemotherapy for B-cell lymphoma.

3.4. Treatment and Survival

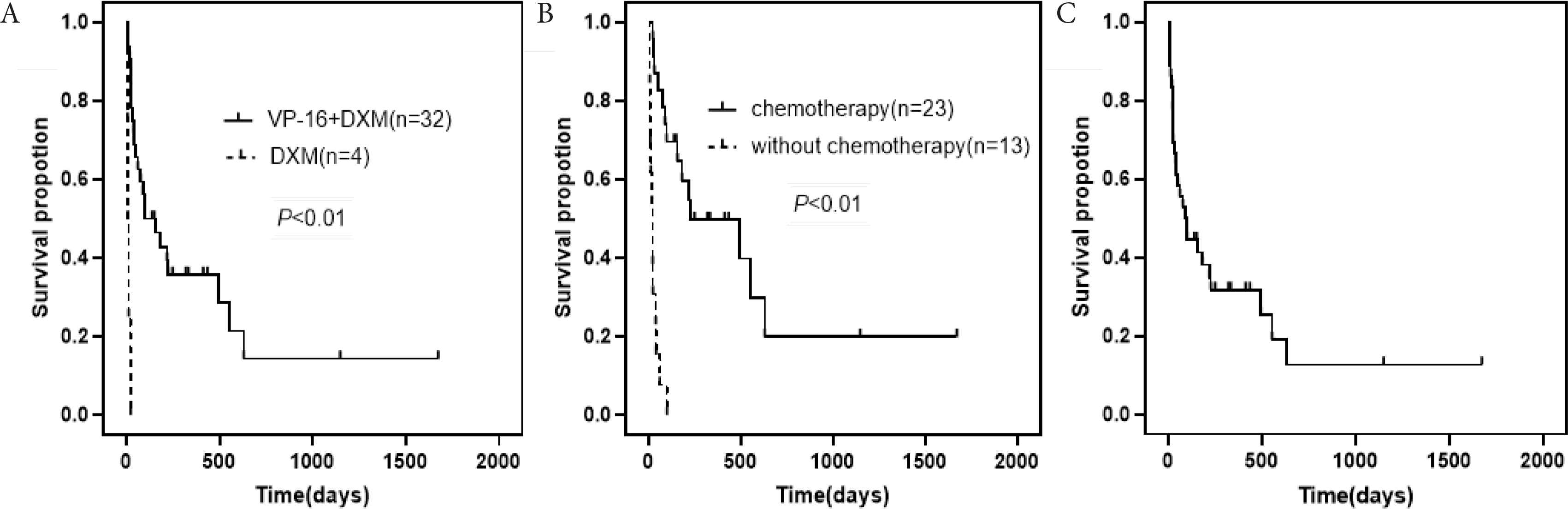

Induction therapy of HLH was based on HLH-2004 protocols including etoposide, dexamethasone and cyclosporine A. After the initial control of HLH (i.e. normal temperature, lowered ferritin, lower triglycerides, rising blood cell count, and lowered transaminases), the patients were actively transitioned to lymphoma chemotherapy. Four patients, who received dexamethasone only, seemed to have a poorer prognosis (median survival time: 9.5 days) than 32 patients treated with etoposide-involving regimens (median survival time: 117 days) (χ2 = 20.037, p < 0.001; Figure 2A). Twenty three patients underwent based on the HLH-2004 protocol combined with multidrug chemotherapy (median survival time, 217 days) with a significantly improved OS compared to 13 patients that only received treatment according to the HLH-2004 regimen (including patients that received dexamethasone only) (median survival time, 21 days) (χ2 = 30.744, p < 0.001; Figure 2B). Of those patients that received a multidrug chemotherapy, 17 patients received chemotherapy plus rituximab (median survival time, 248 days) but did not exhibit an improved prognosis compared to three patients who did not receive rituximab (median survival time, 180 days) (χ2 = 0.412, p = 0.521).

(A) Patients treated with etoposide-involving regimens vs. patients receiving dexamethasone (median survival time, 117 vs. 9.5 days). (B) Patients that underwent based on HLH-2004 protocol and multidrug chemotherapy vs. patients that received treatment according to the HLH-2004 regimen (median survival time, 217 vs. 27 days). (C) Kaplan–Meier survival analyses of patients with B-LAHS.

Survival curve is depicted in Figure 2C. Following a median follow-up of 92 days (range: 22–301 days), 27/36 patients (75%) had succumbed. The early mortality rate of 36 patients with B-LAHS was approximately 13.9% at 2 weeks after bone marrow aspiration, 33.3% at 1 month, and 44.4% at 3 months. Among them, two patients with EBV infection progressed more rapidly and died within 8 days after bone marrow aspiration, and the remaining 34 patients without EBV infection had a longer survival time, with a median survival time of 97 days (range: 24–322 days), suggesting EBV infection may be used as a reference indicator of a poor prognosis.

4. DISCUSSION

Hemophagocytic syndrome is a kind of inflammatory response syndrome, which is caused by unbridled activation and proliferation of lymphocytes, monocytes and macrophages, an excessive secretion of a large number of inflammatory cytokines, that accumulates in multiple systems and organs, and is progressively aggravating, rendering it extremely life-threatening [9]. According to its etiology, primary HLH and secondary HLH can be distinguished. The former is an autosomal or sex chromosome recessive hereditary disease, more common in children, while the latter is more prevalent in adults, such as in malignancies, during infections, autoimmune diseases, pregnancy, transplantation, and immunosuppression phases [10,11]. The prognosis for MAHS patients is even worse than that for the rest of the secondary HLH patients with a median survival time of 1.13 months in the former and less than one year in the latter group [12]. In contrast to LAHS with a sound underlying database, only a few data of B-LAHS is available. In a study comprising 1239 lymphoma patients, LAHS accounts for only 2.8%. Among the LAHS patients, the number of B-LAHS cases is significantly lower than that of T/NK-cell LAHS (T/NK-LAHS) (1.8% vs. 8.2%), the survival is relatively good, and the early mortality is 10.5% within the first 120 days after developing LAHS [13], which is lower than that of this study. Previous studies showed that B-LAHS, compared to T/NK-LAHS, is characterized by an older age of onset, an improved survival and a low detection rate of EB virus particles [14]. Nonetheless, the overall prognosis of HLH secondary to B-cell lymphoma remains poor. The case fatality rate of the 36 patients comprising cohort in this study was 13.9% within 2 weeks and 33.3% within 1 month, indicating that B-LAHS progressed rapidly and that a delayed treatment could be fatal. Therefore, timely detection of suspected cases and early diagnosis is very important. Moreover, we should actively look for potential causes and control the primary disease in order to prevent the recurrence of HLH [15].

Epstein–Barr virus infection has been confirmed to play an important role in the occurrence and development of T/NK-LAHS [16]. However, the exact pathogenesis of B-LAHS is still unclear. When combining previous data with those of our study the onset characteristics of the 36 patients can be summarized as follows. Firstly, there are abnormalities in the TLR/MYD88/NF-kB signaling pathway of nonGCB subtypes in DLBCL. Excessive activation of CD8+ leads to the T cells production of pro-inflammatory cytokines which in turn can promote the development of HLH [17]. Of the 25 patients with DLBCL in our study, 23 were of a nonGCB subtype (92%). Our findings are supported by data of Yeh et al. [18] who could show that this feature in DLBCL is associated with HLH. Secondly, multi-cycle chemotherapy or long-term immunosuppressive therapy leads to immunosuppression, resulting in an immune cell deficiency, especially of CD8+T cells and natural killer cells. This will finally end up in a persistent infection status which further promotes the occurrence of HLH [19]. In this study, four patients developed HLH after multi-cycle chemotherapy, with a median of eight cycles (range: 7–10) cycles. Two patients received maintenance therapy with lenalidomide after chemotherapy and one patient received maintenance therapy with cyclophosphamide. Another patient, that was suffering from aplastic anemia, was treated with an oral immunosuppressant after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, followed by a new onset of DLBCL associated HLH and was diagnosed as EBV infected. Neoplastic B-cells secret cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α and IL-10) [20], that may lead to multiple organ dysfunction. In 10 out of 36 patients, the level of the inflammatory factors IL-10, IL-6 and IL-8 was elevated which is basically consistent with the literature. Currently, it is not clear whether EBV infection plays an important role in the occurrence of B-LAHS. In this study, two patients with EBV infection may be the clinical overlap between EBV-driven HLH and EBV-driven B-LAHS.

Hemophagocytic lymphohistocytosis may occur prior to the lymphoma diagnosis, at the same time of initial presentation, or during treatment [4]. Diagnosis is still based on the HLH-2004 standard for children, however, this may not be transferable to the adult HLH situation, especially those of early HLH patients [21]. Due to the limitation of hospital equipment and the rapid progress of the disease, individual indicators such as NK-cell activity and sCD25 analysis detection cannot be obtained in time. If the diagnosis tightly sticks to the HLH-2004 standard, by this it is likely to delay treatment and therefore reduce the survival of patients [5]. Persistent fever, elevated ferritin, hypocytopenia and splenomegaly were the most common manifestations in this study which is in accordance with the tetralogy of abnormal indicators proposed by Wang [22]. Previous studies have shown that serum ferritin ≥10,000 μg/L has a 90% sensitivity and a 96% specificity, however, this conclusion is drawn from the pediatric population [7]. In our adult study, the median of the serum ferritin level was 2929.5 μg/L, 50% of the patients had a level above 5000 μg/L, and only 28% of patients showed levels of ≥10,000 μg/L. Reduction of hemoglobin levels and platelet counts are common causes of hypocytopenia but not leukopenia. The latter may be associated with infection leading to an offset of leukopenia in HLH by the increase of leukocyte reactivity caused by infection. In our study, hemophagy occurred in the bone marrow in half of the patients in our study, but the sensitivity and specificity of this parameter was not high. Therefore, treatment should not be delayed due to the analysis of this single parameter [23]. It is worth noting that the levels of IL-10, IL-6, and IL-8 in combination increased significantly in 10 patients that were analyzed for inflammatory factors, which may be of greater significance for the early diagnosis of B-LAHS in adults than other parameters. In addition, we found a prominent abnormal liver function, mainly involving increased transaminase levels, decreased albumin levels, and increased direct bilirubin levels, indicating that LAHS is involving the liver. According to the potential etiology of B-cell lymphoma, most of the patients are middle-aged to elderly, most of them display a nonGCB subtype of DLBCL, are in Ann Arbor stage is stage IV and B-cell lymphoma has invaded the bone marrow. Therefore, B-LAHS is highly likely suspected in middle-aged and elderly patients displaying bone marrow invasion of B-cell lymphoma with persistent fever, elevated ferritin, hypocytopenia and splenomegaly. At the same time, the levels of inflammatory factors should be detected perfected as soon as possible.

At present, there is no definite prognostic model for B-LAHS. In our study, two EBV-infected patients died within 8 days after bone marrow aspiration biopsy suggesting that EBV infection is likely to accelerates the disease progress and may thus leads to a poor prognostic for adult B-LAHS patients. The treatment of LAHS should be aiming at suppressing the hyperactive immune system and treating the underlying diseases [24]. The etoposide-based induction treatment of HLH inhibits the activation of mononuclear macrophages and reduces the production of inflammatory factors by Bergsten et al. [25]. In this study, patients who received etoposide-based induction regimens survived significantly longer than those who received dexamethasone alone. The results of a combined multidrug chemotherapy were also significantly better than those without chemotherapy. This survival benefit indicates that the treatment of primary disease is as important as the treatment of HLH itself. In our previous study, we suggested that chemotherapy plus rituximab might improve the prognosis for B-LAHS patients [26], however, we did not observe a survival benefit which may be related to the limited number of cases involved.

This study has several limitations one of which is the fact that not for all patients NK-cell activity and soluble CD25 levels could be detected. Furthermore, the study is a small sample retrospective study so that future prospective, multi-center, randomized controlled large sample studies are needed to further verify the relevant prognostic factors, the treatment and the survival characteristics of B-LAHS patients.

5. CONCLUSION

To sum up, B-LAHS is relatively rare, and the overall prognosis is poor, especially in middle-aged and elderly patients, and the early rate mortality is high. The combination of an etoposide-based induction therapy together with a multidrug chemotherapy to treat the primary disease, is a reasonable choice for B-LAHS treatment leading to a prolongation of the survival time of the patients. However, a concomitant EBV infection may be a poor prognostic factor.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

Qingjiang Chen, Xudong Zhang, Mingzhi Zhang and Huting Hou contributed to the study conception and design. Yue Zhang and Qing Wen gathered the data. Jingjing Ge and Yaxin Lei conducted the statistical analyses and interpretation. Huting Hou, Siyu Qian and Zeyuan Wang drafted the manuscript and figures. Meng Dong, Xiaojuan Zhang and Xiaoguang Duan revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. The authors critically reviewed and validated the final version of the manuscript.

FUNDING

The

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Huting Hou AU - Xudong Zhang AU - Siyu Qian AU - Zeyuan Wang AU - Meng Dong AU - Xiaojuan Zhang AU - Xiaoguang Duan AU - Yue Zhang AU - Qing Wen AU - Jingjing Ge AU - Yaxin Lei AU - Mingzhi Zhang AU - Qingjiang Chen PY - 2021 DA - 2021/12/04 TI - Clinical Features and Prognosis of B-cell Lymphoma-associated Hemophagocytic Syndrome: A Retrospective Single Center Study JO - Intensive Care Research SP - 45 EP - 50 VL - 1 IS - 3-4 SN - 2666-9862 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/icres.k.211129.001 DO - 10.2991/icres.k.211129.001 ID - Hou2021 ER -