Hospital admissions among immigrants from low-income and foreign citizens from high-income countries in Spain in 2000–2012

- DOI

- 10.1016/j.jegh.2016.07.002How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Foreigners; High-income countries; Low-income countries; Public hospital

- Abstract

Over the last decade, the number of foreign nationals in Spain has increased. Our aim was to report the trends in hospital admissions, differentiating between foreign nationals from high-income countries (HICs) and from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) in a public hospital. A retrospective analysis of hospital admissions in patients aged ⩾15 years between 2000 and 2012 was performed by means of hospital information systems at a public hospital in the city of Alicante, Spain. During the period of the study, 387,862 patients were admitted: 32,020 (8.3%) were foreign, 22,446 (5.8%) were from LMICs, and 9574 (2.5%) were from HICs. The number of foreign nationals, foreign nationals from LMICs, and foreign nationals from HICs admitted increased from 1019, 530, and 489 in 2000 to 2925, 2097, and 828, respectively in 2012. A total of 27.5% of patients were admitted for pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium, especially foreign nationals from LMICs (34.3%), and 14.1% of foreign nationals were admitted for cardiovascular diseases (14.1%), which were more common in those from HICs (26.3%). The number of admissions among foreign nationals from LMICs increased significantly in all the diagnoses, but in pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium, the increase was higher. In conclusion, nearly one out of 10 adult patients admitted to our hospital was foreign, mainly from LMICs, and the main reason for admission was diagnoses related to pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium.

- Copyright

- © 2016 Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

1. Introduction

Immigration to Spain is a relatively recent phenomenon, showing a dramatic increase in the number of foreign inhabitants from 637,085 (2.9% of the Spanish population) in 1998 to 5751,487 (10.9% of the Spanish population) in 2012 [1]. Immigrants can be roughly divided into two large groups: those from high-income countries (HICs) in Europe and North America, including those living in traditionally tourist destinations like in Southeastern Spain; and economically disadvantaged immigrants from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), predominantly from Latin America and Northern Africa [1,2].

In Spain, the national health system is financed mainly by taxes, providing universal primary, specialized, and hospital care, which was free at the point of service for all users until September 2012 [3]. Foreigners could register in their municipality of residence to gain access to healthcare, regardless of their legal status [4].

The immigrant population is made up of people with different ethnicities, genetic backgrounds, and behavioral patterns, which are factors that can be related to disease [5]. Moreover, the immigrant population, especially from LMICs, is a vulnerable group characterized by low employment levels, limited social support, below-average access to education, communication difficulties, and lower socioeconomic status compared with Spanish citizens, which causes discrimination [6,7]. Scientific evidence shows that this kind of discrimination is related to hypertension [8], self-rated ill health [9], and mental health problems [10].

In Europe, several epidemiological studies have explored the hospital utilization patterns of foreign residents [11–13]. A few studies have evaluated the impact of this migratory phenomenon on the use of hospital admissions in the Spanish healthcare system [14,15]. Nevertheless, the scientific evidence of trends in hospital admissions in the Spanish healthcare system is scarce [16,17]. An overview of these trends could help us to assess immigrants’ healthcare needs and the potential impact on their health if these services are not available.

We consider it to be of interest to compare the use of hospital services between Spanish nationals, immigrants from HICs, and those from LMICs. Our aim was to report on trends in hospital admissions, differentiating between foreign nationals from HICs and those from LMICs in a public hospital in Alicante (Spain) from 2000 to 2012.

2. Methods

2.1. Design and setting

We performed a retrospective analysis of admissions at the Hospital General Universitario de Alicante (HGUA), Spain. We excluded individuals aged <15 years due to the difficulty in classifying their immigration status. In January 2012, HGUA provided hospital services to a total population census of 253,000 inhabitants in metropolitan Alicante. Information about hospital discharges was obtained from the hospital information systems from 2000 to 2012. A total of 387,862 admissions of patients aged ⩾15 years from 2000 to 2012 were included in the analysis.

2.2. Variables

This study defined foreign residents as people without Spanish citizenship. Immigrants can only be granted Spanish nationality in restricted circumstances, so we identified the immigrants admitted based on their self-reported citizenship. We divided the population into Spanish citizens, residents from HICs (25 European Union countries, plus Switzerland, Iceland, Norway, US, Canada, Japan, and Australia), and immigrants from LMICs (all other countries). We then classified immigrants from LMICs according the their region of origin: Northern Africa and the Middle East, Latin America, Eastern Europe, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia.

Hospital admissions data from 2000 to 2012 were obtained from the hospital information systems. The following data were collected at each visit: demographic characteristics, nationality, and diagnosis at discharge. The diagnoses at discharge were performed according to the main diagnostic groups detailed in the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) [18].

The Committee for Data and Research Protection of the Hospital General Universitario Alicante granted ethical approval to this study.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 21.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) and p < 0.05 was considered significant. We carried out a descriptive analysis of variables according to the population groups described above, applying the Pearson χ2 method for bivariate comparison of proportions, and calculating the odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The measure of trend was calculated by OR using the referral category “the year 2000” and the χ2 test for trend.

3. Results

A total of 387,862 patients aged ⩾15 years were admitted during the study period, including 32,020 (8.3%) foreign nationals: 22,446 (5.8%) from LMICs and 9574 (2.5%) from HICs. A higher proportion of immigrants from LMICs were women compared with those from HICs (66.5% vs. 47.7%, p < 0.001). Approximately 89.1% of people from LMICs were aged 15–64 years, compared with 64.1% of those from HICs (p < 0.001). Table 1 shows the ranking of the 40 regions and countries whose citizens were admitted most frequently to HGUA. Two-thirds of all the foreign people admitted to the hospital were citizens from Latin America and the European Union.

| Region | Country | Admission | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin America | 11262 | 35.2 | |

| Colombia | 2856 | 8.9 | |

| Ecuador | 2818 | 8.8 | |

| Argentina | 2017 | 6.3 | |

| Cuba | 531 | 1.7 | |

| Bolivia | 529 | 1.7 | |

| Uruguay | 465 | 1.5 | |

| Paraguay | 355 | 1.1 | |

| Dominican Republic | 279 | 0.9 | |

| Brazil | 270 | 0.8 | |

| Peru | 240 | 0.7 | |

| Chile | 196 | 0.6 | |

| Mexico | 117 | 0.4 | |

| Others | 589 | 1.8 | |

| Western Europe | 9441 | 29.5 | |

| UK | 2747 | 8.6 | |

| France | 2604 | 8.1 | |

| Germany | 973 | 3.0 | |

| Italy | 443 | 1.4 | |

| Switzerland | 356 | 1.1. | |

| Portugal | 341 | 1.1 | |

| Poland | 266 | 0.8 | |

| Norwegian | 207 | 0.6 | |

| Sweden | 155 | 0.5 | |

| Others | 1349 | 4.2 | |

| Northern Africa | 6103 | 19.1 | |

| Morocco | 4177 | 13.0 | |

| Algeria | 1884 | 5.9 | |

| Others | 42 | 0.1 | |

| Eastern Europe | 2614 | 8.2 | |

| Romania | 1196 | 3.7 | |

| Russia | 593 | 1.9 | |

| Ukraine | 316 | 1.0 | |

| Armenia | 144 | 0.4 | |

| Others | 509 | 1.6 | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 1508 | 4.7 | |

| Nigeria | 466 | 1.5 | |

| Senegal | 240 | 0.7 | |

| Guinea | 158 | 0.5 | |

| Others | 664 | 2.0 | |

| Asia | 959 | 3.0 | |

| China | 253 | 0.8 | |

| Pakistan | 104 | 0.3 | |

| Others | 620 | 1.9 | |

| North America | 123 | 0.4 | |

| USA | 101 | 0.3 | |

| Other | 22 | 0.07 |

Regions and top countries of the 32,020 foreign nationals admitted in the study period.

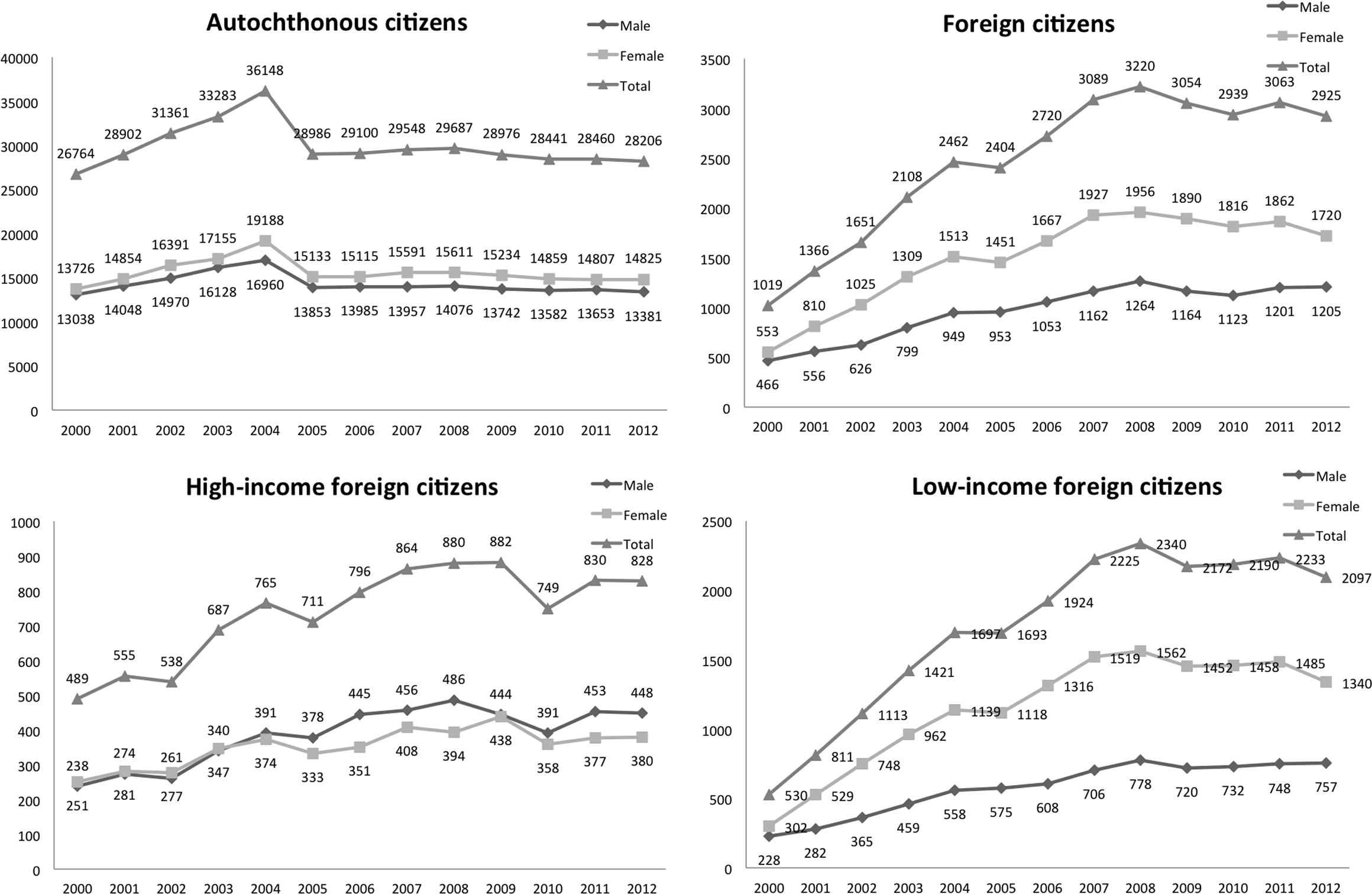

Hospital admissions of total foreign nationals, people of LMIC origin, and people from HICs increased from 1019, 530, and 489 in 2000 to 3220, 2340, and 880 in 2008. After that, there was a slight decrease to 2925, 2097, and 828 for each respective group. Fig. 1 shows the trends in the number of hospital admissions according to sex for people of LMIC origin and people from HICs compared with Spanish citizens. It is interesting to note the steadily higher increase in admissions of women from LMICs than women from HICs compared with Spanish citizens.

Evolution of hospital admissions in Spanish citizens, total foreign nationals, people from low- to middle-income countries, and people from high-income countries, by sex (2000–2012).

The main diagnostic groups according to population are presented in Table 2. The admission diagnosis differed between groups: people from LMICs were primarily admitted due to pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium (34.3%), whereas people from HICs presented to hospital with cardiovascular diseases (26.3%).

| Main diagnostic group | Total foreign nationals | People from LMICs | People from HICs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Pregnancy, childbirth, & puerperium | 8795 | 27.5 | 7696 | 34.3 | 1099 | 11.5 |

| Cardiovascular system | 4501 | 14.1 | 1986 | 8.8 | 2515 | 26.3 |

| Digestive system | 3157 | 9.9 | 2294 | 10.2 | 863 | 9.0 |

| Injury and poisoning | 2799 | 8.7 | 1786 | 8.0 | 1013 | 10.6 |

| Neoplasms | 2556 | 8.0 | 1545 | 6.9 | 1011 | 10.6 |

| Respiratory system | 1826 | 5.7 | 1266 | 5.6 | 560 | 5.8 |

| Genitourinary system | 1729 | 5.4 | 1354 | 6.0 | 375 | 3.9 |

| Nervous system & sense organs | 1281 | 4.0 | 926 | 4.1 | 355 | 3.7 |

| Musculoskeletal system & connective tissue | 1132 | 3.5 | 767 | 3.4 | 365 | 3.8 |

| Symptoms, signs, & ill-defined conditions | 1122 | 3.5 | 791 | 3.5 | 331 | 3.5 |

| Others | 996 | 3.1 | 565 | 2.5 | 431 | 4.5 |

| Infectious & parasitic diseases | 720 | 2.2 | 544 | 2.4 | 176 | 1.8 |

| Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases, & immune disorders | 479 | 1.5 | 308 | 1.4 | 171 | 1.8 |

| Skin & subcutaneous tissue | 371 | 1.2 | 219 | 1.0 | 152 | 1.6 |

| Blood & blood-forming organs | 284 | 0.9 | 208 | 0.9 | 76 | 0.8 |

| Congenital anomalies & perinatal conditions | 163 | 0.5 | 128 | 0.6 | 35 | 0.4 |

| Mental disorders | 109 | 0.3 | 63 | 0.3 | 46 | 0.5 |

| Total | 32020 | 100 | 22446 | 100 | 9574 | 100 |

HIC = high-income country; LMIC = low- to middle-income country.

Main diagnostic groups in foreign nationals: total, from LMICs, and from HICs (2000–2012).

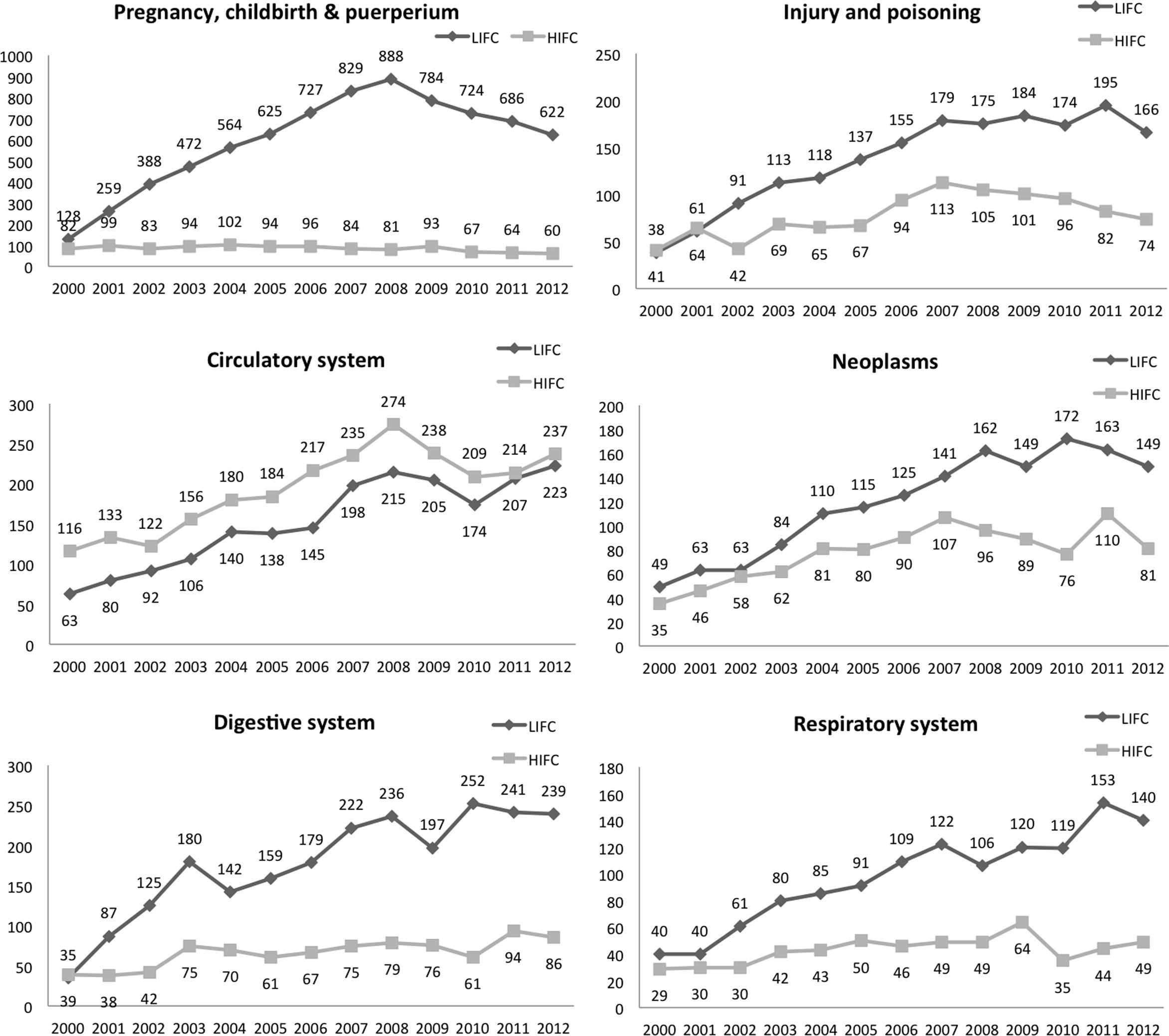

Fig. 2 shows the trends in the number of hospital admissions in people from HICs compared with people from LMICs for the main diagnostic groups. Although the number of admissions for people of LMIC origin increased significantly for diagnoses, it was higher for pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium (χ2 for trend = 182), rising from 128 cases in 2000 to a peak of 822 in 2008, followed by a steady decrease.

Evolution of hospital admissions in people from low- to middle-income countries (LIFC) and from high-income countries (HIFC), for diagnostic groups relating to pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium; cardiovascular system; digestive system; injury and poisoning; neoplasms; and respiratory system (2000–2012).

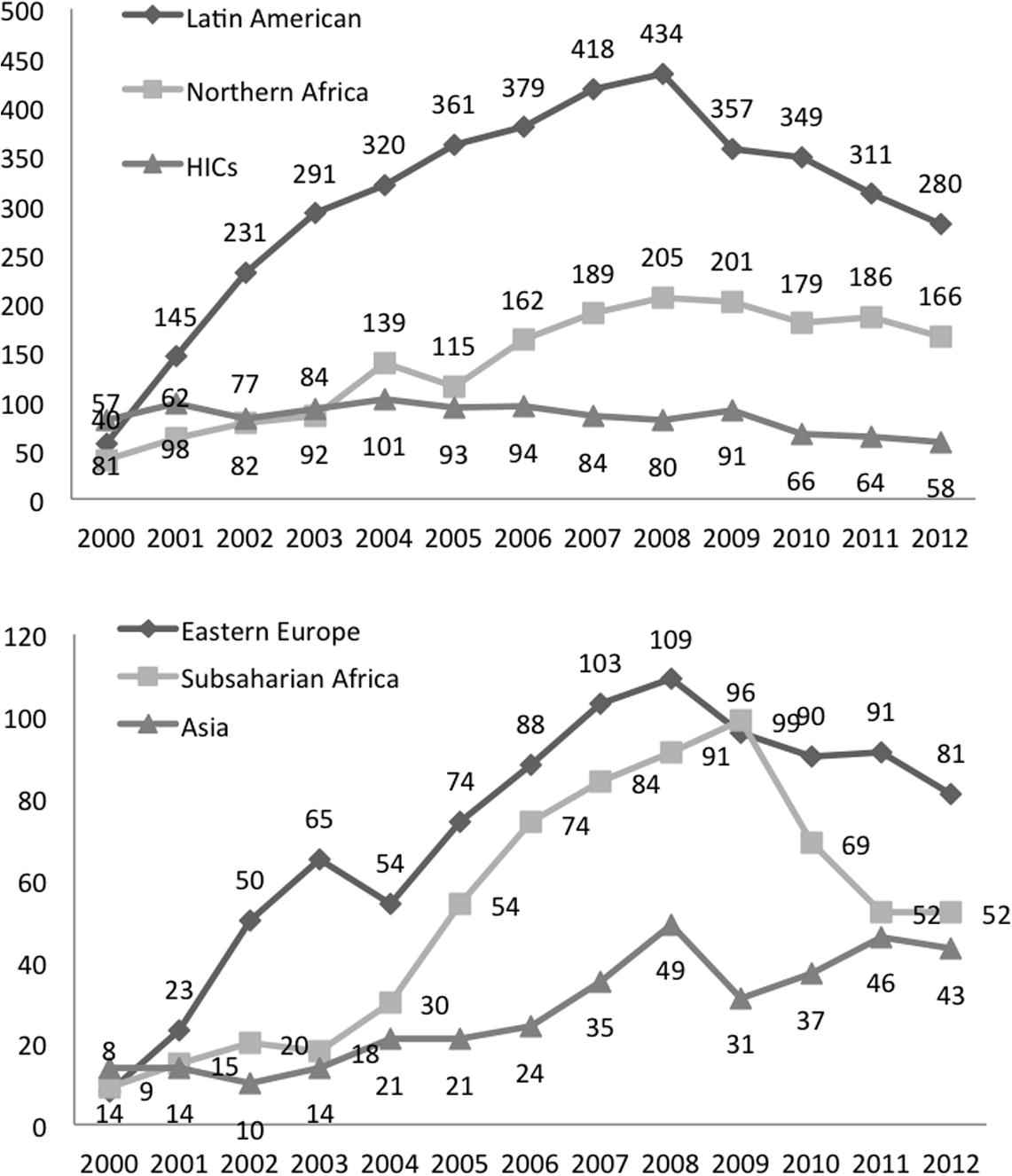

Of the 8795 admissions related to pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium in foreign nationals, 87.5% were in women from LMICs, compared with 12.5% in women from HICs (p < 0.001). The prevalence of admissions related to pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium was significantly higher in all the regions corresponding to LMICs: Latin America (34.9%), Northern Africa (29.6%), Eastern Europe (35.7%), Sub-Saharan Africa (44.2%), and Asia (37.4%). In fact, the OR for pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium in women from Latin America and women from all other remaining regions was 1.82 (95% CI: 1.17–3.26). The significant increase in the number of cases of pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium was higher in women from Northern Africa, followed by Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America (χ2 for trend was 35, 29, 16, 13, and 6, respectively). The number of cases in women from HICs decreased significantly from 82 in 2000 to 60 in 2012, compared with women from LMICs (χ2 for trend = 182). Fig. 3 depicts the trend in pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium in women admitted to our hospital. The number of women from Northern Africa, Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Eastern Europe who were admitted for pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium increased from 2000 to 2008, before beginning to descend until the end of the study period in 2012.

Evolution of hospital admissions in foreign women due to pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium, according to region of origin: (2000–2012).

4. Discussion

Admissions among foreign nationals increased during the study period, especially in people of LMIC origin. After 2008, the number of admissions stabilized or slightly decreased, probably because of the reduction in the number of immigrants in Spain [1,19]. This could be a result of emigration, since 417,023 foreign citizens emigrated in 2012 – 17% more than in 2011 [1,19]. Moreover, in 2012, there were 16.1% fewer foreigners residing in Spain than in 2011. The main reason for these changes in immigration and emigration was the economic crisis [20,21].

The prevalence of pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium in women from LMICs in our study was 27.5%, which is similar to that reported in an Italian study (28.3%) [13,17]. In contrast, only 11.5% of admissions for this diagnostic group were in people from HICs. Other Spanish and European studies also report a comparatively high incidence of delivery and abortions in this group [22–25], as reflected by a greater proportion of hospitalizations in these women than in women from the country under study and other immigrants from HICs [13,17,23–25]. Thus, reproductive health for immigrants from LMICs seems to stand out as a clearly emerging need.

However, from 2008 on, there was a reduction in the number of admissions for pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium, which was higher in Latin American women than for other nationalities. This could be due to the higher rate of emigration and the recent decrease in immigration to Spain, or to a lower birth rate brought on by the economic crisis [1,19,20]. Other drivers of this trend may include the socioeconomic causes of the recession, the low birth rate in the general population in Spain, a reduction in the number of women from Latin America, and cultural differences with other demographic origins, as seen in other studies [25,26]. It can be speculated that after the decrease in the number of admissions for pregnancy (signifying the slowing growth in the immigrant population), we can expect to see an increase in chronic diseases as the remaining immigrants grow older. It is also worth noting that the number of admissions for pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium in women from HICs has decreased since the beginning of the 21st century.

Admissions for other diagnoses, such as for cardiovascular diseases, increased in residents from both HICs and LMICs during the study period. An important group of diagnoses worldwide [15,27], the cardiovascular disease profile is nevertheless likely to be different in patients from HICs and LMICs, because the median age in the former group is higher than in the latter. Also, a large proportion of cases were from HICs, where risk factors for atherosclerosis, such as tobacco, stress, unhealthy diet, and sedentary behavior, are more common than in LMICs (although that trend is changing) [28].

Admissions for injury and poisoning peaked in 2009 and then began to decrease until 2012 in people of LMIC origin. This immigrant group is more vulnerable to injuries; a fact that Cacciani et al. [12] postulated might be related to poor living and working conditions. This hypothesis is supported by surveys of occupational injuries conducted in Spain [29] and Italy [30], which suggest a higher risk of injuries for immigrants.

For its part, cancer is a global and growing, but not a uniform problem. Millions of people will continue to be diagnosed with cancer every year for the foreseeable future [31]. All these patients need access to optimum healthcare. As in our study, the admission for neoplasms increased in people from HICs and LMICs.

Admissions for respiratory diseases in particular increased in people of LMIC origin, probably due to environmental pollution (chemical warfare or fumes from cooking oil), as well as climatic factors, cultural habits, or disorders unique to the regions corresponding to LMICs [32,33]. Therefore, in our study, this was a common problem with respect to admissions in people from LMICs, although the number of cases also increased in residents from HICs.

What is the implication of these analyses as it relates to the Spanish healthcare system? Our results compare trends of hospital admission between Spanish citizens and foreign nationals from HICs and LMICs to assess their needs and the impact on their health. Our findings suggest that foreign nationals from HICs are considerably older than those from LMICs; a large proportion of whom are of child-bearing age.

The main limitation of this study was that it only focused on admitted patients and did not include outpatient consultations or visits to the emergency room. Consequently, we only analyzed the most severe cases that required hospital admission. Another limitation stemmed from the study period, which ended in December 2012. Just prior to that, in September 2012, a new Spanish law [34] rendered most undocumented immigrants ineligible to receive free healthcare except under special circumstances such as pregnancy and emergency assistance.

5. Conclusion

Nearly one in 10 adult patients admitted to our hospital is a foreign national, primarily from LMICs, mainly admitted due to pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium. Admissions in these groups rose quickly until their peak in 2008, followed by a steady decrease in the 4 years that followed.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Lorraine Mealing for assistance with editing.

References

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - José M. Ramos AU - Héctor Pinargote AU - Eva M. Navarrete-Muñoz AU - Alejando Salinas AU - Jaume Sastre PY - 2016 DA - 2016/08/18 TI - Hospital admissions among immigrants from low-income and foreign citizens from high-income countries in Spain in 2000–2012 JO - Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health SP - 295 EP - 302 VL - 6 IS - 4 SN - 2210-6014 UR - https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jegh.2016.07.002 DO - 10.1016/j.jegh.2016.07.002 ID - Ramos2016 ER -