“Letters from” during the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic

- DOI

- 10.2991/artres.k.200810.001How to use a DOI?

- Copyright

- © 2020 The Authors. Publishing services by Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

Dear All

I hope this finds you safe and well and learning to adapt to the “new normal”. 2020 has been a tumultuous year for all of us with all scientific meetings, including our own ARTERY 20, either cancelled or held virtually online, giving us little or no opportunity for personal interaction and scientific networking. I have therefore commissioned a special feature for the current issue of Artery Research “Letter from”. For this feature I have asked members of ARTERY and our supporters to write short letters from wherever they are around the world. In these letters the authors give short updates as to how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected them personally in their respective cities and countries worldwide.

I am delighted to report that the response has been very positive and I hope very much that you will enjoy reading them and it will serve, in some small way, to bring us together during these difficult times. I hope that many of you will be able to take part in what will be a virtual online meeting of ARTERY20 in October, with final details to be announced shortly.

Finally, wherever you are, stay safe and well and I look forward to being able to see many of you in person, if socially distanced, before too much longer.

LETTER FROM BOTSWANA

One of the most useful pieces of advice I have seen about the COVID-19 pandemic is to “remember this is a marathon, not a sprint”. I am writing from Botswana, where we have, so far, an epidemic on a small scale, with less than 1000 cases and two deaths. But we have a long and quite porous border with South Africa, which has the most cases in Africa and where the epidemic is still accelerating. It feels as though we are just managing to keep the infection at bay, but the future remains very uncertain. For example, although the initial stringent national lockdown was eased after two months at the beginning of June, in the last couple of weeks we have had a petrol shortage and rationing because of a strike of South African truck drivers, partly in response to mandatory testing at the border. Several clusters of COVID-19 cases sent Gaborone and the surrounding area back into full lockdown from midnight yesterday (30 July), at three hours notice. Perhaps this explains the sombre tone of this letter!

Botswana is relatively well-placed to weather the COVID-19 pandemic. Governance is much better than in neighbouring countries, there are functioning government clinics and schools in even the smallest, most remote communities, local government mostly works quite well, and there are established social safety nets for the poorest. All these are positives in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic and its collateral socio-economic and public health effects, which in many low- and middle-income countries will kill more than the virus.

The country has experience with a previous viral pandemic. In the early days, AIDS was rapidly fatal and ravaged the population of Botswana and other countries in Southern and East Africa. Botswana has been a global leader in the AIDS pandemic. It was among the first countries to offer free ARVs to people infected with HIV and virtually eliminated mother to child transmission of HIV. Preventing new infections has been much less successful, and young Batswana women especially continue to face high risks of HIV infection, related to high rates of gender violence and risky transactional, intergenerational sex. Our own work here addresses these issues. Sadly, there is already early evidence that here, as in other settings, the COVID-19 lockdown and economic stresses have exacerbated these problems, reversing any recent advances. There will be a lot of catching up to do.

On a personal level, I am very fortunate. I live some 20 km outside Gaborone, with open bush all around, so have every opportunity to exercise outdoors as much as I want, even in strict lockdown. A local farm delivers fresh eggs and vegetables. Our electricity supply has been mostly quite reliable during the lockdown (I hesitated to write this for fear of spooking it!). I have a decent (by local standards) internet connection and have been able to continue work with colleagues and students remotely very effectively throughout. The police on the lockdown roadblocks are always kind and courteous and have allowed me to visit my nearest shops (15 km away) with no problem every couple of weeks. The neighbourhood wildlife is often quite interesting. A local family of monkeys visits regularly and is intent on entering through my study window despite social distancing rules. The picture shows a couple of mabolobolo (puff adders) found outside the back door and quickly despatched. There are many, many worse places to be during this pandemic.

LETTER FROM BRITISH COLUMBIA…

Since receiving the invitation to contribute “a letter from British Columbia” I have spent considerable time thinking about the potential focus for my musings. Firstly, as an exercise physiologist focused on comparative and evolutionary physiology I wondered whether the Editor might have appreciated comment on the zoonotic nature of COVID-19 and how the many NGOs caring for great apes around the world are managing the COVID-19 pandemic; given the ever-present risk of bi-directional zoonoses these organisations deal with, their veterinary teams are probably some of the best prepared and informed and should probably be the ones providing advice to the governments and institutions currently (mis)managing the crisis. Secondly, as a recent export to Canada I wondered whether readers may have been interested in a comparison of the relative merits and weaknesses of the UK and Canadian research ecosystems. They are remarkably different and in many ways the T-Shirt slogan “our grass really is greener” from the well-known Canadian clothing company (Roots) does hold some water, especially in relation to the funding opportunities and the relative respect exercise physiology receives in Canada. Thirdly, I considered trying to unpick the relative pros and cons of the rampant “covidisation” of all research – at this precise moment do we really need researchers spending time and funds examining how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted (insert your favourite spurious research connection here), however, Dr. Madhukar Pai from McGill has already done an outstanding job of this [1].

Ultimately, I decided that I would use this opportunity to share some of my own professional learning from the COVID-19 pandemic. As the current Director of the School of Health and Exercise Sciences at UBC-Okanagan I have the great fortune of working with an outstanding group of faculty. A group of these academics lead the Centre for Heart Lung and Vascular health whom every two years run the Okanagan Cardiovascular and Respiratory Symposium (https://okcrs.org/) – an international meeting targeted specifically at the development and training of talented young cardiovascular scientists. This year the symposium was slated to start on the 12th of March with ~150 delegates from around the world converging on Silver Star mountain resort in British Columbia. Early in the year the organizing committee were confident and excited about hosting a phenomenal meeting – the emerging news from Wuhan was being followed with interest but certainly wasn’t raising the organizer’s blood pressure. However, in the couple of weeks preceding the conference, and as the global impact of the virus unfolded, we were increasingly aware that COVID-19 was going to impact the meeting – but to what degree? At this point in time, myself and the conference organisers were happy to fall in line with the provincial and institutional position, and based on their assessment that “…the public health risk associated with COVID-19 was low for the general population” it was our intention to continue with the conference as planned. However, in the week immediately preceding the conference (~5th–6th March) we received a number of concerned messages from speakers and delegates, some of whom work with immunocompromised patients, some from countries already advising against international travel, and some from clinician-scientists worried about their ability to return to work in the ICU on return from the meeting. In addition, based on close monitoring of news and media outlets our own anxieties related to the developing situation and global implications were mounting.

On Tuesday 10th March we found ourselves in a less than ideal position – a number of speakers had arrived, or were en route, a number delegates from the UK and Australia were being advised not to travel by their own institutions, but our own institution and province were still suggesting that the overall risk was low (there were very few cases in BC and all were in Vancouver), and so they were not actively recommending the cancellation of events or activities. Personally, and professionally, we were conflicted – as a School of Health and Exercise we didn’t want to be responsible for bringing the first case of the virus into the region (not a great headline for any institution), we also didn’t want colleagues and students to be stranded in Canada following the potential rapid imposition of travel restrictions during the conference; but equally, we didn’t want to make a decision that contradicted the institutional or provincial position. Ultimately, after much debate and deliberation, we made the call to cancel the symposium on the afternoon of the 10th, one day before the WHO confirmed the virus as a pandemic. Some may suggest that we should have acted sooner, and with hindsight I do not disagree, however, at the time we were scrambling for advice to base our decision on – not understanding that those we were looking to for guidance were dealing with far greater challenges and decisions that had implications way beyond those we were trying to mitigate. On reflection, we are pleased that we made the call when we did, we still had to deal with the financial implications and the task of getting a small number of international speakers back home, but we averted the potential nightmare of having many delegates stuck in British Columbia and also minimized the potential reputational damage that may have been caused had we proceeded. Overall, this experience has been a stark lesson in decision-making and taking responsibility for one’s own area of influence; faced with a similar challenge in the future I would like to think that all involved will respond rapidly and decisively knowing that their institution wants them, and expects them, to make decisions at challenging moments. Ultimately, had we made an earlier decision to cancel the symposium and the virus had not taken hold, the worst that we could have been accused of would have been over-cautiousness – better that, than to be labelled foolhardy.

REFERENCE

DISPATCHES FROM FLORIDA ON COVID-19

I semi-retired from the University of Florida College of Medicine a few years ago and I am now a Professor Emeritus. It took a few years but I finally settled into a “more or less” daily routine after I finished writing a couple of books; one medical textbook with co-authors Drs O’Rourke, Edelman and Vlachopoulos; “McDonald’s Blood Flow in Arteries 7th Edition” and the other an autobiography “A Life Remembered: Memories of a Sharecropper’s Son”. Most mornings, during the week, I would meet friends at Starbucks for coffee and socializing and Saturday morning I would meet up with a group of motorcyclists for a morning breakfast ride. During March of each year my biker friend and I would attend “Bike Week” in Daytona Beach, Florida and “Gatornationals” NHRA Drag Races in Gainesville, Florida and my Starbucks friends and I would attend the “Concours d’Elegance”, an exotic car show in Amelia Island, Florida. During the summer I would travel abroad usually to countries I had not visited before and in the fall I usually attended the European Artery Society Annual Conference somewhere in Europe. At other times I would attend the University of Florida sporting events such as football, basketball, and baseball. The Gator 2020 Baseball team was on fire at the beginning of the record-breaking season winning 15 straight games which started February 10. Also, I had booked a Baltic Cruise for me and my daughter, Cami, leaving from Copenhagen, Denmark June 27 and traveling to Stockholm, Sweden, St Petersburg, Russia and Tallinn, Estonia. The life I had planned for myself after the death of my lovely wife Arlene after 56 years of marriage, was going along pretty well. Then, on January 20, 2020, a patient in the United States was given a diagnosis of infection with a coronavirus by the state of Washington and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The coronavirus is known as SARS-Cov-2 and the disease as Coronavirus Disease 2019 (or COVID-19), but no worries, because our self-proclaimed stable genius President who did not know what COVID-19 was, reassured the American people on TV February 10, that the China virus would go away. Again, on February 26 after 15 Americans had tested positive for the virus he repeated his claim that the virus would just go away. By the middle March, the pandemic was so severe the country was shutdown and all establishments were closed and all sporting events cancelled, including the Gator baseball season. In addition, mine and Cami’s cruise was cancelled and we were terribly disappointed because the two of us had not been on a trip together for over 20 years. Not long after the shutdown, the number of COVID virus cases began to decline and then, beginning the latter part of June individual states began opening bars, beaches, hair salons and etc and the number of cases began to increase again. During the next five months our President repeated his claim 20 more times that the virus would just disappear without a vaccine. Finally, after we had over 4 million cases of COVID-19 and over 146,000 deaths our President said the reason we had so many cases was because we tested more than any country in the world and that the USA was the envy of the rest of the world because he was doing such a great job and everything was under control. By July 27 Florida, my state of residency, had a total of 441,900 documented cases of COVID-19 and 6,116 deaths and both are still increasing. After the shutdown was lifted, it was like the whole country thought the pandemic was over. The health experts keep telling us to wear a face covering, abide by the social distancing rules and wash hands often. I wear a mask but I do not look like the Lone Ranger. Americans have been banned from traveling to almost every country in the world, including Mexico and the Bahamas. My travels abroad have been curtailed and I am not happy about that. It appears as though we are on the verge of another shutdown. However, a lot of Americans are against it, but that may be the only solution, to combat the spread of the virus. Lots of people in this country refuse to wear a mask even in a crowd, to social distance and to wash their hands. The leaders of this country have done a terrible job handling the contact and spread of the COVID virus. One last note; there is no solid evidence at the present time that drugs such as hydroxychloroquine or budesonide are beneficial in the prevention or treatment of COVID-19. However, our president keeps saying that hydroxychloroquine is beneficial and others say that budesonide is. There are clinical trials in progress at the University of Oxford in England and Queensland University of Technology in Australia to determine if budesonide is an effective treatment for COVID-19 and my friends at the University of Cambridge in England are investigating the beneficial effects of hydroxychloroquine in the clinical trial PROLIFIC.

LETTER FROM GERMANY

It is a pleasure to watch the children closely while playing. The good old board games that we played when we were young ourselves, long before everything went electronic. Watch how they think, how they take decisions in the game. How clever they are to set up a trap for mom and dad. How they carefully weigh up, or sometimes simply take their steps impulsively just as a child will do. Before COVID-19, we did not have the time to make these detailed observations. Or better, we did not allow ourselves this time. Everyday life was packed with school, kindergarten, music lessons, soccer training, scout groups, playing with friends and much more. But on March 16, the day of the shutdown, schools and kindergartens were closed, as were all other leisure options. Suddenly the moment came to spend more time with the family. During these weeks we have largely isolated ourselves, which was the recommendation of the authorities. It is a stereotype that Germans like to follow rules in a very disciplined manner. It though plays in favor of this stereotype, that when we are children we learn a proverb that goes: “whoever says A must also say B”. It means that whenever you start something, you finish it. Always. Come what may. This saying goes hand in hand with another proverb that we learn as we grow older: “who can celebrate can also work”. Since we all enjoy to celebrate, what it actually means is: you have to work. Always. Come what may. Sometimes it does give me a smile, whenever I realize that I have fully accepted these idioms and pass them on to my children. In relation to COVID-19, this passion for following guidelines meant that the great majority in our country largely followed the rules set up after the shutdown, very precisely. Distance rules, hygiene etiquette, contact minimization. This discipline became an important jigsaw piece in the containment of COVID-19. And here and there, one can also hear a slightly proud undertone when the foreign press reports on the comparatively small number of fatalities in Germany. But, great part of the truth is that we were lucky not to be the first to be hit by the outbreak. The pictures of our neighbors from northern Italy have contributed largely to the fact that the pandemic and its consequences have been taken very seriously in this country. As of April 20, we have started to partially lift the shutdown. The first shops were allowed to open their doors again. Despite the massive restrictions during these difficult weeks, I also feel deep happiness. Happiness to spend more time with the kids. Happiness to have a very patient woman by my side. Understanding the children better, more intensely seeing them grow up. And also to fulfill our pedagogical responsibility. Deciding when to let them win at the board games so they do not lose their motivation. But also when we should win to encourage them to get even better. However, our eldest, Anna, has already won against us, even if we had not previously planned this pedagogically. So COVID-19 will also be the time when we proudly learned how wonderful it is to be beaten in the game by our own daughter.

LETTER FROM GENT

This letter from Gent is actually a letter from Lede, a town about 30 km east of Gent and about halfway to Brussels, where my residence has been my new office for over 2.5 months now since COVID-19 also hit Belgium and the country went into lockdown on March 13th. Belgium has been hit relatively hard; with over 9000 people dying on a population of 11 million, we had our share. Fortunately, our health system never really got into problems; the alarming and saddening images from Italy led to an unseen preparedness and reorganization of complete hospitals creating a capacity of over 2000 intensive care beds, of which just over 1200 got occupied at the peak of what will probably be the 1st wave of the pandemic. The country is now opening up little by little, analyses are being made of what went well and what didn’t. The COVID-19 crisis even resulted in some kind of political stability and gave us a temporary minority government – we had elections on May 26th in 2019 but we are still without a federal government that is supported by a majority in parliament. Not easy to make a coalition in a country where about half of the country votes center-left (the Walloon region) with a substantial fraction voting far-left, while the other half votes center-right (the Flemish region) with more than a substantial fraction voting far-right (where we believe/ hope that the extreme votes are just out of frustration, not because of a desire for communism or fascism), parties vetoing each other and doing little to build confidence and a basis to find a structure that may work for our beautiful but oh-so-complex and surrealistic country. It doesn’t help in the crisis we are experiencing to have 5 ministers being responsible for the purchase of personal protective equipment. Anyhow, COVID-19 has wiped off the blackboard; the economic cemetery and financial crater ahead may just be what Belgium needed to overcome the political immobility that we have been struggling with for decades (we are world record holder with a solid 541 days without government).

But enough of this; I was asked to write about how COVID-19 has impacted my life and way of working. I was and still am among the lucky ones living in a large house on the “countryside” with a large garden, two grown up kids studying at university (in Gent, what else) and a wife working for the municipal music school. So this has all been very well bearable, without personal worries (as of yet) about income losses and we have had quite harmonious 9 weeks now, where we have tried to keep some rhythm and structure with week and weekend activities (I have a.o. been exploring walking trails in Lede with surprisingly beautiful landscapes scattered around in some of the urban and suburban ugliness). There are moments that I genuinely feel guilty of being this privileged. But I am also becoming tired of the whole situation. I have seen my office twice in the past 9 weeks; being a professor in the faculty of engineering and architecture, teleworking has been the norm for me and I fear that it will stay the norm for quite some more time. As any university world-wide, we have also switched to on-line teaching from one day to the other, discovering all the different online platforms available and their complexity. I don’t think that I ever put more effort in preparing materials, and students are seemingly very happy with all recorded classes and having all these extra materials. But what do I miss is the interaction with my biomedical engineering students in class; talking in front of a camera without getting any feedback is frustrating; I even miss the feeling of students getting bored when explaining the concept of impedance – there is certainly an advantage there in demonstrating wave intensity analysis using a water hammer video! I also miss the day-to-day spontaneous interactions and coffee meetings with my PhD students in my lab – this has all been replaced by Teams meetings (which – I have to admitted – sometimes work better). We also just started a brand new BSc in biomedical engineering program – an achievement that I am quite proud of as chair of the BSc/MSc program – and I had to unfortunately interrupt the 1st edition of a bachelor project where students were measuring pulse wave velocity using ultrasound and PPG. But they will nonetheless be the first generation of biomedical engineering students in Gent with a clear notion of arterial stiffness! I also long for the first scientific meeting to attend physically. It was quite frustrating to find meetings getting cancelled one after the other – curious what the online alternatives of some of them will be like, but I cannot imagine that these will come close in replacing physical meetings. For sure, they may be more efficient and we don’t lose time travelling and will reduce our ecological footprints, but I always felt the need for these meetings, being energizing mental breaks and events to look forward to catching up with colleagues – some of whom feeling more like friends – pick up new ideas and exchange experiences. I am most happy that some interactions do continue within the VascAgeNet COST action network activities, so well led by Christopher and his enthusiastic team. They also set up an action to support the clinical colleagues within the network with some video messages – happy to share a frame from my own video with you!

It is all pretty much unclear what the future will bring, but this period will for sure also pass. It will probably have a permanent impact on the way we do some of things we do, but I also hope that we can soon regain the direct human interaction in our profession. Ang get that haircut!

Take care, stay safe and see you soon!

A LETTER FROM NORTH AMERICAN ARTERY… IN THE TIME OF COVID-19

At the time of writing this letter, the North American Artery (NAA) 10th annual meeting should have been taking place May 22–23 in Iowa City, USA with the theme “Early Detection and Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease.” We had an outstanding slate of speakers planned for plenary lectures, symposia, tutorial lectures, trainee abstract oral presentations and of course the popular debate. At the time the NAA Program Committee decided to cancel the meeting on March 10, 2020, there were 936 COVID-19 cases and 34 deaths in the U.S. As of this writing there are now >1.8 million COVID-19 cases in the U.S. and >104,000 deaths. About 1 week after the decision to cancel, many of us in academic research and higher education in North America (and around the world) had our research halted suddenly, had to quickly transform our classroom teaching to on-line instruction, while many young investigators also found themselves home schooling their children at the same time. Hospitals in the U.S. quickly changed patient care delivery to tele-health visits and cancelled “non-essential’ procedures, while dealing with enormous surges in intensive care patients and absorbing devastating economic loss from COVID-19.

Celebrating the end of the 2019 NAA 9th Annual meeting on the way to dinner with a few ‘Artery legends’ in the middle seats.

Front row seats (from L to R): Profs. Demetra Christou and Gary Pierce; Middle row seats (from L to R): Profs. Charalambos “Babis” Vlachopoulos, Wilmer Nichols, and Alberto Avolio; Rear row seats (from L to R): Profs. Tina Brinkley and Stella Daskalopoulou.

Most of us in North America still have not returned to our laboratories, but when we do return it will surely be different. Extra personal protective equipment for routine clinical research, informed consent procedures done virtually, reduced staff in the lab, re-designing the physical space of our laboratories to maintain social distancing and new strict disinfection protocols to name a few of these changes. This will be the ‘new normal’ of biomedical research for the foreseeable future, but what about the future of scientific meetings? In the coming year, we will be limited to virtual meetings and webinars where scientific content will be exchanged, but will we ever get back to face-to-face conferences? Over the past month, there has been much speculation of what scientific conferences of the future will look like post-COVID-19. I have heard a range of predictions from colleagues and professional societies – “all meetings in the future will be virtual”; “meetings of the future will be a ‘hybrid’ model (combination of virtual and face-to-face)”, and “all meetings will be back to face-to-face once there is a vaccine for COVID-19”. I recently attended some virtual presentations from a professional meeting that was cancelled in April. Although the presentations were excellent and virtual platform worked well, I must say that observing hundreds of faceless ‘Zoom squares’ of the audience (other than the slides and face of the speaker) was a bit depressing. Clearly scientific content can be delivered successfully via virtual presentations, questions and answers can occur effectively between the speaker and audience (albeit using the ‘chat’ function’), however, I do not believe virtual webinars will be the future of post-COVID-19 conferences. The ability to network with colleagues and friends, observe and participate in robust scientific exchanges ‘in person’, and witness light-hearted ‘jabs’ during Artery debates (the image on a slide of Prof. Gary Mitchell’s face being grilled ‘on the barbie’ during an Artery meeting presentation by Prof. Jim Sharman is forever seared in my mind), I don’t believe can be replaced by virtual webinars. Furthermore, the social aspects of hand-shakes, hugs, bows with our Japanese colleagues, and enjoying good laughs and ‘libations’ with colleagues from around the world, does not exist in the virtual space. Indeed, it is this combination of ‘in-person’ robust scientific exchanges and social comradery at our global Artery community of meetings (i.e., Artery, NAA, LATAM and Pulse of Asia) that keeps us coming back year after year.

As we begin to re-plan the NAA 10th annual meeting for May 2021, we remain cautiously optimistic that NAA will resume as an ‘in person’ conference next year. Until then, I will continue to reflect on this fond memory from one year ago (see photo) driving a few ‘Artery legends’ to dinner in Iowa City during a heavy rainstorm at the end of final day of the 2019 NAA 9th annual meeting. For NAA updates, you can follow us on Twitter @NAASociety.

COVID-19….LETTER FROM NEW YORK!

March of 2020, the novel coronavirus brought the city that never sleeps to a complete pause. Our hospital was tending to more than double the number of patients that it was designed for. All hospital associates were declared “essential” to the response to this pandemic. Physicians, nurses, and technicians, irrespective of their areas of expertise, were summoned to the frontlines of this war against the common enemy. As cardiologists, we were called upon to provide critical care in makeshift critical care units. Clad in our personal protective gear, we were back to being full time physicians who practiced more the art of medicine than that of electronic charting or obtaining insurance approvals. All our efforts were dedicated to understanding the pathophysiology of this disease and the myriad of its presentations. But COVID-19 was unforgiving and every human casualty took its toll on our mental and physical wellbeing. In an otherwise socially distant city, the common enemy brought about a sense of togetherness never seen before.

Our only hope was an evidence-based approach to this disease and we considered it to be our responsibility to add meaningful evidence to the existing data pool. Even so, as we spent our “post-call” hours gathering data from the many patients we cared for, we found ourselves sucked into a race against time and a battle against enormous datasets. We saw manuscripts where the author-to-study cohort ratio seemed rather disproportionate, a surge in pre-prints that never made it to any journal, hundreds of new trials, innumerable case reports on every aspect of the disease, epidemiological studies performed by non-epidemiologists – you name it. We read articles so distant from the reality we were drenched in, that we wondered about their authenticity and reproducibility. This went on even after we had seen the peak of COVID-19, but only until the so-called “post-publication review” identified massive loopholes in a handful of highly regarded studies. In this hysterical race to be the first and the brightest to publish, the integrity and quality of medical research became the next big casualty of COVID-19.

Similar to sailing in the dark while looking at the stars to find our way home, when navigating a pandemic we depend on rigorous research that upholds the necessary standards, to advance our understanding and to answer important questions that could help save lives. Instead, we witnessed the emergence and propagation of pandemic research exceptionalism.

As clinician-researchers in the making, the lessons learnt from this pandemic went far beyond those taught at the patients’ bedside. It took a microscopic virus to show us that the things that truly mattered were not “things” after all. More importantly we were reminded, “Knowledge without integrity is dangerous and dreadful”.

LETTER FROM PARIS IN TIME OF COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic arrived in France one week later than in Italy, the first European country struck by the virus. Although I am a physician, I was not prepared, as most French people, to witness day after day such an exponential increase of infected patients, particularly those requiring hospitalization and intensive care. The lockdown occurred on March 16 in France, and since, my life has changed. Afterwards, I can distinguish three phases.

The main changes occurred during the first two weeks of lockdown, during which I was stunned. I stayed at home in Paris with my wife. The first task was to get news from family and friends. Like all French people, we were allowed to go out for one hour a day, not more than one kilometer away from home, which we did early morning in empty streets. Impossible to kiss our children and grand-children. An important challenge was to understand this novel disease. I gave priority to scientific journals. They initially published limited data, mainly from the Chinese experience, and sophisticated basic science in virology and infectious disease. It was necessary to complete this picture by epidemiological data comparing the epidemic in various European countries, quite scarce at this time, and by high quality news that can be found in some international websites and French newspapers like “Le Monde”. Phone calls to colleagues and friends working on the front line of the COVID fight were much more informative than watching on TV terrifying images of COVID patients in emergency room and intensive care unit. This is a period during which I realized for the second time in my life that I was “too old”. The first time was 18 months ago when I was 65 and I had to retire because this is mandatory in France for chiefs of department in public hospitals (they have the possibility to continue until 68 as simple physician). The second time was during the COVID epidemic, when I tried to register as physician for helping colleagues in hospital or working on COVID follow-up platforms. Each time, the answer was “too old”, i.e. older than 65, thus at high risk of COVID complications. Please, stay at home! Thus, I decided to adopt the Irish proverb “A good retreat is better than a bad stand”.

The second phase was marked by an urgent need to continue science and medicine in this new world. A good opportunity came from various scientific requests, among which the analysis of the relationship between hypertension and COVID-19. All hypertension specialists came to the same conclusions at the same time: (a) hypertension per se is not a risk factor for susceptibility to COVID-19 infection and does not affect the outcomes of those infected; and (b) there are no clinical data in humans to show that ACEIs or ARBs either improve or worsen susceptibility to COVID-19 infection nor do they affect the outcomes of those infected. It was satisfying to see that numerous learned societies published similar statements at the same time. By contrast, a number of colleagues did not resist an opportunistic behavior, well noticed by several chief-editors of scientific journals. They submitted a large number of “clinical cases”, “point of views”, and “reviews” on various hypothetical pathophysiological mechanisms leading to supposedly more effective and/or less deleterious therapeutic strategies of the COVID infection in general, and in the present case, advocating the necessary discontinuation of antihypertensive treatment, or at least ACEIs and ARBs, or even ACEIs only or ARBs only … (!) Retrospectively, this fuss was only of minor importance. Much more distressing was the debate on whether it is better to follow the recommendations of politicians and businessmen (high level of immunity in the population by doing “business as usual”) or those of scientists and healthcare workers (lockdown, thus dramatic reduction of hospitalizations and deaths), a debate that was fortunately concluded in favor of the scientists and physicians. Hopefully, the role of public health, public hospitals and social security will be reinforced after the COVID pandemic. During those days, nothing warmed my heart more than the round of applause for healthcare workers, every day at 8 pm, that gathered locked-down inhabitants at their window or balcony all around Paris and everywhere in France…like in many countries. New faces, new smiles, new friends. April 6th marked the peak of COVID deaths.

The third phase, characterized by hope and expectancy, started at the end of the lockdown (May 11th) and is still ongoing today, June 2nd. Yet, there is no sign of a second wave. What we have to do “in order to protect ourselves as well as others” will hopefully remain a mantra for months. But, even more importantly, we should relate our personal consumption and behaviour to large-scale problems such as climate change, pollution, biodiversity loss and natural resource depletion, that may have played a role in the COVID pandemic. Strangely enough, as a premonition, 6 months before the COVID pandemic, I started a series of paintings (my favorite hobby) on the theme of the opposition between individualism and fraternity-solidarity, and I took advantage of the lockdown to complete 3 paintings showing groups of people in ambiguous posture. For instance, a swimming competition gathering hundreds of participants; a demonstration with ambitious Union leaders close to usual citizens; a long line of visitors in a museum spending more time taking selfies than looking at masterpieces…

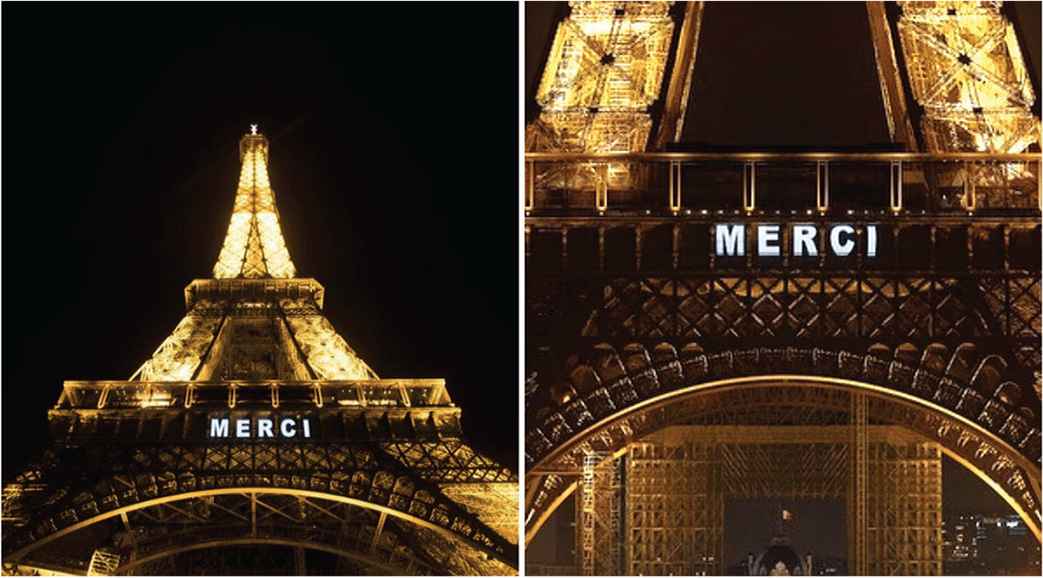

In conclusion, I would like to share a picture of the Eiffel tower displaying “MERCI” (thank you) in big letters as an acknowledgement to healthcare workers on the front line of the COVID fight. I view it also as a reminder for the French government and French citizens that the post-COVID word cannot be the world from before. I trust the new generation in finding the right way to do so.

LETTER FROM ROTTERDAM

From The Netherlands, such as from different North European countries, we have been observing this unknown epidemic attacking first the South European countries such as Italy and rapidly spreading all over Europe. We have been expecting the wave to move to The Netherlands, looking at the increasing impressive amount of COVID patients.

This has given us a little more time to prepare ourselves to this impact. The Erasmus MC University Medical Center in Rotterdam has rapidly chosen for a place in the frontline in this war becoming the coordinating center for the COVID crisis in The Netherlands. The department of Internal Medicine where I am working has taken the lead in the organization of the medical care for the expected COVID epidemic within the hospital. This meant tight daily meetings in order to reorganize the medical care in our center and transform wards into COVID dedicated-wards according to clear timelines dependent on the number of referring patients. The tight organization and the active attitude have given to all of us healthcare professionals at the Erasmus MC a safe feeling in a period of great uncertainty.

After the first period of scary increasing numbers of referrals at the ICU and the COVID dedicated-wards, we have learned to recognize and treat these new category of patients. Thanks also to the efforts of colleagues who decided to mainly participate in COVID activities in order to facilitate the learning process and offer the most adequate medical care. We have rapidly observed that these patients could be cured and saved, we have seen a decrease of COVID referrals which has given us, eventually, the chance to try to go back a pseudo normal life.

This means that nowadays we have daily digital medical briefing and educational moments through video platforms. When we started this, it was quite challenging to find the fine tuning; actually, after a first exploring period now we are able to have a good interaction during all the meetings. Today, at 1:00 p.m. I will be member of the commission to examine a PhD candidate in a fully digital PhD graduation ceremony. However, it is still advised to all participants to adhere to the customary dress code, so I will wear my gown. The research activities are slowly starting again, the laboratories have experienced the most challenges but it seems we step now in a positive stream.

Also my private life has been suffering this epidemic. Fortunately no (serious) disease in the local inner circles. Conversely, as stated long time ago, survival of the fittest suggests us to find novel ways of living. So, my cover band Sticky Fingers was forced to cancel all the gigs previously planned (I am the singer and lead guitarist), moreover we were not even able to have rehearsals. However, when things became steady I invited the friends (n = 3 + 1) of the band for a rehearsal in my garden. In this way we were able to have much fun, in complete respect of all the rules on social distancing. And to offer some fun to my neighbors. We already did this three times, next weekend again.

All in all, this is a weird period and we all want to go back to normality. Carefully and safely.

WADING THROUGH THE TIME OF COVID-19 AT BONDI, SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA

While strolling on the silky white sands of Bondi Beach, accompanied by the foamy surf and the periodic crash of the waves of the Pacific Ocean, I was contemplating on how to start this letter. By the time I got home after a one-kilometre walk, it came to me. Dubai International Airport, the airport with the world’s highest level of international traffic.

There was something very different about the passenger terminal of Dubai airport when I landed there on Emirates flight EK415 at 1:20 pm on 5 February 2020. I had been through that passenger terminal many times, and at any time of day or night there was always high-level activity in shops, airport lounges, waiting areas, and with people moving about with a sense of purpose. This time, the people movement looked distinctly different; a type of slower locomotion, melancholy look on the faces of the duty-free shop assistants, just fewer people everywhere, and with the conspicuous absence of Chinese travellers.

I was not meant to be at Dubai airport on the 5th of February. My trip from Sydney to Paris to attend the 12th International Workshop on Structure and Function of the Vascular System (6–8 February, 2020) was confirmed on Air China to go through Beijing. This was so that on the return journey after the Paris meeting, I would spend the rest of February in China to visit and work with collaborators in Beijing and Shanghai. However, as the potential effects of the novel coronavirus in Wuhan started to become evident, with news of possible banning of flights from China to Europe, my itinerary was changed to an Emirates flight, just before the last Air China flight was allowed to land on European soil. The extra time in Europe allowed me to visit my daughter and her family in Konstanz, Germany, and to attend the inaugural Working Group Meeting of the European COST Action “Network for Research in Vascular Ageing” (VascAgeNet) in Paris (19–21 February).

When I returned to Sydney on 26 February, there was talk of a potential temporary pause, in case the novel coronavirus made a significant appearance in Australia. By then the World Health Organisation had officially named the novel coronavirus “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2” (SARS-CoV-2) and the associated disease, COVID-19. The timespans were somewhat confused; there was talk of a few weeks, maybe a few months, and things could return to normal. When I left for Paris in early February, it seemed that I could still use my 90-day Chinese visa to go to China, maybe in April. When I returned, I had to accept that I would need to get another visa – but not sure for when!

The government decisions on the extent of the required lockdown were being made with daily monitoring of potential infections, and Bondi Beach elevated its world fame to being the location of the biggest cluster in Australia of COVID-19 positive tests. Notwithstanding the closure of almost everything, we had only a partial lockdown, with reasonable outdoor movement and with observation of the usual directives of government and medical authorities.

In addition to having to rapidly adapt to online delivery of lectures and various platforms for video meetings with research colleagues, the lockdown also coincided with the period for major research grant applications in Australia. This might also be considered a useful effect of the lockdown, contributing to a type of uninterrupted period in which to concentrate on writing activities. But there are also other side-effects of enforced ‘stay-at-home’ directives. Without too many significant and pressing external demands, one slowly converges to a level of mental and physical activity determined by one’s natural biorhythm. This can lead to wonderful explorations of other creative spaces, such as musical journeys in the composition of piano pieces as a gift for one’s granddaughter on her 8th birthday.

Now in late July, looking at the clear and sharp horizon across the ocean, I realise that the sand and surf at Bondi Beach will be the same for a long time to come. But the glaring changes I saw at Dubai airport in the early stages of the pandemic told me that some other things we have always accepted as just being there, like the sand and the surf, will never be the same again.

Sand and Surf at Bondi Beach during the time of COVID-19 (March–July, 2020)

LETTER FROM THE VASCAGENET CORE GROUP IN TIME OF COVID-19

The VascAgeNet (COST Action CA18216, www.vascagenet.eu) is an international network which aims to refine, harmonize and promote the use of vascular ageing measures [1]. The current pandemic has influenced the way that many work within the network composed of clinicians, engineers, company representatives and researchers. Some are fighting the virus on the frontline, to whom we pay our highest respect and thanks to (https://youtu.be/Q5rTI_5lEpI), while others are adjusting to their new working environment at home. We look back fondly on the great memories from our last meeting in Paris a couple of weeks ago, when the world seemed like a different place. The coming weeks and months are uncertain. The main missions of VascAgeNet (e.g., physical meetings, training schools and short time scientific missions for early career investigators and conference grants) are currently stopped and may be affected in the long-term.

Although, there are currently a lot of measures restricting our private and working lives, our COST Action, VascAgeNet, carries on as planned. We are continuing with the working group activities using online tools, developing webinars and are trying to maintain the momentum of the Paris meeting. Despite the significant challenges to our working lives and collaborations, there are a number of new opportunities and possibilities that have arisen. In the following, we as the VascAgeNet CORE Group, want to share some of these experiences with you:

- •

“Home office reduces physical contact with peers and colleagues but offers the chance for more family quality time!” (Christopher, Chair, AT).

- •

“This period confirmed to me the huge power of digital technology, collective intelligence and family!” (Elisabetta, Vice Chair, IT).

- •

“My observation from the daily stroll with my kids during my paternal leave: asking people to stay home has increased their outdoor physical activity substantially (Remark: Going out for physical activity was/is currently not forbidden in AT).” (Bernhard, WG1 Leader, AT).

- •

“Videoconferencing is the norm nowadays to stay connected with family, friends and colleagues. Spending more quality time with family is a plus!” (Jordi, WG2 Leader, UK).

- •

“This crisis revealed the important things in life. It showed us alternative ways of communicating respecting the environment. People risked their lives to save others. All these make me optimistic about the next day.” (Dimitrios, WG3 Leader, GR/UK).

- •

“My research priorities have completely changed: now I am full-time investigating the long-term consequences of COVID-19 on the vascular system. I hope to expand this project thanks to VascAgeNet (Rosa Maria, WG4 Leader, FR/IT)”.

- •

“While working from home, I have become familiar with using technical tools, such as video cutting and webinar tools.” (Rachel, WG5 Leader, FR/AU).

- •

“Thanks to the experience made on a COVID-19 unit, I can see more clearly that doing good research and spreading the research culture is as important as taking care of the needs of any single patient” (Giacomo, Short-Term Scientific Missions coordinator, IT).

- •

“Several opportunities appeared in using online meeting tools and statistical skills. I had to evaluate the homework of my students and perform several editorial tasks” (Ioana, ITC Conference Grants Manager, RO).

- •

“As a clinical doctor who faces the COVID-19 situation in practice, useful communication tools, social media, websites and much faster communication than usual help to be in touch with colleagues from all over the world and to be well informed about all new information in order to fight this pandemic.” (Milica, Science Communication Manager, RS).

- •

“This situation has created many new challenges for all of us, but it has highlighted our innate ability to adapt and to continue working.” (Chloe, Vice Science Communication Manger, UK).

As can be seen, the experiences are already very diverse within this small group of people and we expect that others within the network will have had different experiences. While there are significant challenges faced by all in the current pandemic, there are also a number of opportunities that have and will continue to arise which will help to make us a stronger, more collaborative and united network. Stay healthy and take care!

Screenshot from an online VascAgeNet CORE Group meeting.

REFERENCE

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - John Cockcroft PY - 2020 DA - 2020/08/20 TI - “Letters from” during the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic JO - Artery Research SP - 187 EP - 196 VL - 26 IS - 4 SN - 1876-4401 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/artres.k.200810.001 DO - 10.2991/artres.k.200810.001 ID - Cockcroft2020 ER -