Counselling services in prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) in Delhi, India: An assessment through a modified version of UNICEF-PPTCT tool

Dr. Bir Singh suddenly demised on 30 March 2012, and he was a part of the present study.

- DOI

- 10.1016/j.jegh.2014.12.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- HIV; PMTCT; PPTCT; Counselling services; India

- Abstract

The study aims to assess the counselling services provided to prevent mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) under the Indian programme of prevention of parent-to-child transmission of HIV (PPTCT). Five hospitals in Delhi providing PMTCT services were randomly selected. A total of 201 post-test counselled women were interviewed using a modified version of the UNICEF-PPTCT evaluation tool. Knowledge about HIV transmission from mother-to-child was low. Post-test counselling mainly helped in increasing the knowledge of HIV transmission; yet 20%–30% of the clients missed this opportunity. Discussion on window period, other sexually transmitted diseases and danger signs of pregnancy were grossly neglected. The PMTCT services during the antenatal period are feasible and agreeable to be provided; however, certain aspects, like lack of privacy, confidentiality of HIV status of the client, counsellor’s ‘hurried’ attitude, communication skills and discriminant behaviour towards HIV-positive clients, and disinterest of clients in the counselling, remain as gaps. These issues may be addressed through refresher training to counsellors with an emphasis on social and behaviour change communication strategies. Addressing attitudinal aspects of the counsellors towards HIV positives is crucial to improve the quality of the services to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

- Copyright

- © 2014 Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

1. Introduction

The prevalence of HIV infection in adult women in India was 0.25% in 2009 [1]. And 5% of the total HIV infections in India are attributed to parent-to-child transmission [2]. Over 90% of new infections among infants and young children occur through mother-to-child transmission [3]. Usually, 20% to 45% of infants of HIV-positive mothers may become infected, with an estimated risk of 5%–10% during pregnancy, 10%–20% during labour and delivery, and 5%–20% through breastfeeding [4,5]. This risk of mother-to-child infection can be reduced substantially through prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) (which is referred to as prevention of parent-to-child transmission (PPTCT) in India to emphasize the role of the father in both the transmission of infection and the management of the infected mother and child) [2,6–11]. In India, the PPTCT programme was started in the year 2002, and these services were integrated with the existing reproductive and child health (RCH) services [12]. In the third phase of the National AIDS Control Programme of India (NACP-III, 2007–2012), voluntary counselling and testing centres were renamed as Integrated Counselling and Testing Centres (ICTC). Since then, PPTCT services are being provided at ICTC-Antenatal Care (ANC) units, separated from ICTC for general public at the medical colleges and up to the district hospital level [13,14]. The programme entails counselling and testing of pregnant women and prophylactic administration of a single dose of Nevirapine to HIV-positive pregnant women and their babies in order to prevent the perinatal transmission of HIV. The counselling component is the key to the success of this programme [4,15]. Counselling is aimed to provide the clients with information so as to enable them to make informed choices. It is further emphasized that information must be sensitive to the patient’s needs that are aimed to break the silence, as well as de-stigmatize HIV/AIDS infection status. Counselling entails eliciting consent to discuss with the client; respecting the client’s rights, beliefs, confidentiality and decision. The components of counselling include: (i) pre-test counselling (intended to provide information on HIV and PMTCT and motivating the patient to undergo HIV testing); (ii) HIV testing; (iii) post-test counselling (to provide the test results, information on preventing the acquisition or transmission of HIV, and information about further care and treatment); and (iv) follow-up counselling and referral (for offering emotional support, HIV prevention and infant-feeding counselling, testing services for partners, and referral to counselling, additional care and treatment services as needed). The PPTCT services are intended not only for HIV-positive clients, but also for HIV-negative clients.

The effective utilization of services depends on the quality of services. Evaluation of these services might suggest ways for their improvement [3]. The literature on PPTCT services is quite low from India, and the available evidence indicates that the acceptance of the programme is slow and delayed [11]. Thus, the present study is taken up with an objective to assessing the counselling services provided to the women attending the PPTCT services.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

Hospital-based cross-sectional study.

2.2. Study setting

Tertiary care hospitals in Delhi, where PPTCT services were established.

2.3. Selection of sites

Five out of 10 tertiary care hospitals, where PPTCT services are offered, selected by lottery method.

2.4. Study population

Women who have received post-test counselling.

2.5. Sample size

The investigator (AKS) made weekly visits to the selected centres (visited one centre in one week) for a period of one year. Women who attended post-test counselling on that day were chosen randomly. In a day, 4–5 women were interviewed, resulting in a final sample of 201 women.

2.6. Inclusion criteria

Women who received post-test counselling at the selected centres were willing to participate and gave consent.

2.7. Selection of participants

Women who have received post-test counselling and consented to participate in the study were selected.

2.8. Data collection

The first author (AKS) interviewed selected women by employing a modified version of the UNICEF-PPTCT evaluation tool. This tool has five sections, namely: (i) demographic characteristics; (ii) clients’ thoughts regarding services received; (iii) HIV voluntary counselling and testing; (iv) infant feeding counselling; and (v) short course of anti-retroviral drugs. As emphasized in the study tool, at least one client each from the following categories viz.: (i) has undergone counselling and testing and found to be negative; (ii) has undergone counselling and testing, found to be positive, but yet to deliver; (iii) has availed counselling, testing, found to be positive, has delivered, has taken nevirapine and is now coming for follow-up, but not on ART for self or for the baby; and (iv) has availed counselling, testing, found to be positive, has delivered, has taken nevirapine and is now coming for follow-up and is now on ART.

2.9. Data analysis

Data were computerized and analysed using Stata 9 (StataCorp LP, 4905 Lake Way Drive, College Station, Texas 88845, USA). Responses were entered as numerical codes for pre-coded questions. For open-ended questions, responses were entered as strings; and similar responses were clubbed by assigning a code number. Analysis was done by the HIV status of the participants.

2.10. Ethics

Ethical clearance was obtained from the institute’s ethics committee, as well as from all five hospitals prior to the study. To ensure privacy, clients were not interviewed in the presence of the counsellors or relatives of the client. Information regarding the study was provided in the local language, Hindi, and for those who cannot read, the contents were read and explained by the interviewer. The participants either signed or gave a thumb impression on the consent form as a confirmation of their consent. Confidentiality of the information was assured. Participation was voluntary; they may refuse to answer any question and choose to stop the interview at any time. Refusing to participate will not affect her or her family’s access to services at this or any other centre. The questions and doubts expressed by the clients were clarified. All the questionnaires were marked with an identity number rather than with personal details of the participants.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic details and HIV status of the participants

A majority (56%) were in the age group of 21–25 years; 60% were in 13–28 weeks of gestational age (Table 1). While 37% completed 10–12 years of education, 26% completed graduation; still, 13% did not receive any formal education. A majority (83%) were homemakers. All were currently married except one widowed.

| Characteristics of clients | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age distribution (in years) | |

| ≤20 | 27 (13.4) |

| 21–25 | 112 (55.7) |

| 26–30 | 48 (23.9) |

| >30 | 14 (7.0) |

| Mean ± SD (range) | 24.69 ± 3.76 (19–39) |

| Current age of gestation (in weeks)* | |

| ≤12 weeks | 19 (9.5) |

| 13–27 weeks | 121 (60.1) |

| ≥28 weeks | 54 (26.9) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 200 (99.5) |

| Widowed | 1 (0.5) |

| Education status | |

| Illiterate | 27 (13.4) |

| Primary | 18 (9.0) |

| Middle | 28 (13.9) |

| Secondary and senior secondary | 75 (37.3) |

| Graduate and post-graduate | 53 (26.4) |

| Occupation status | |

| Home-maker | 167 (83.1) |

| Salaried job/self-employed/casual worker | 34 (16.9) |

| HIV status of the participants | |

| HIV-Negative | 171 (85.1) |

| HIV-Positive but yet to deliver | 23 (11.4) |

| HIV-Positive, had delivered, taken Nevirapine and came for follow-up but not on ART | 6 (3.0) |

| HIV-Positive, had delivered, taken Nevirapine and came for follow-up and was on ART | 1 (0.5) |

SD = Standard deviation.

7 (3.5%) women delivered the child.

Socio-demographic characteristics and HIV status of the study participants.

HIV status is known to all participants as all were post-test counselled women. Out of the total of 201 women, 171 (85%) were HIV-negative and 30 (15%) were HIV-positive. Among the HIV-positive clients, 23 clients (11%) had not yet delivered; 6 clients (3%) had delivered, had taken nevirapine and had come for follow-up, but were not on ART. Only one client was on ART.

3.2. Purpose of visit to the clinic

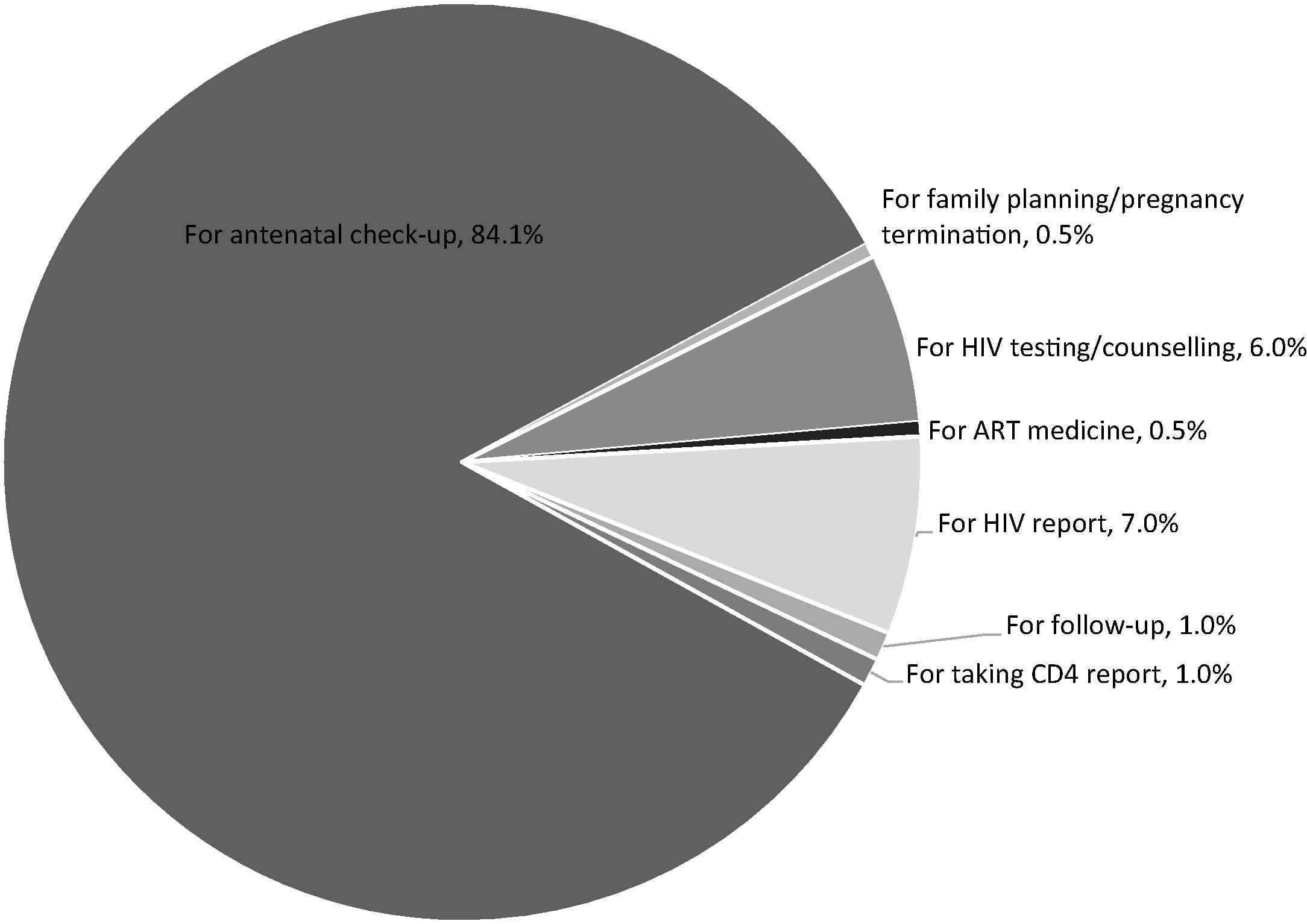

The main purpose of the visit to the clinic was for an antenatal check-up (84%) (Fig. 1). Twelve (6%) clients visited the clinic specifically for HIV testing and counselling, 7.0% visited for taking an HIV report, and one client visited for taking ART medicines.

Purpose of visit to the clinic on the day of interview.

3.3. Issues of PMTCT discussed during the counselling

Table 2 reveals that counsellors discussed various issues mainly with the HIV-positive clients. Counselling focussed on explaining the transmission of HIV among adults (77.2% and 80% HIV-negative and -positive clients, respectively); and on transmission from mother to child (62.7% of HIV-negative and 77.7% of HIV-positive clients). Test results were explained to 96.7% of HIV-positive clients and 73.7% of HIV-negative clients. A great majority (96%) missed the opportunity to know about the window period. Only 7 HIV-negative clients were told about the window period. While 67% of HIV-positive clients were advised on preparation and place of delivery, these aspects were grossly neglected for HIV-negative clients. Discussion on breastfeeding and replacement feeding was held with 73% of HIV-positive clients. Only 27% of HIV-negative clients and 26 out of 29 (90%) (one was a widow) of those tested HIV-positive were advised by the counsellor to bring their respective husbands for counselling. A majority (76%) of HIV-positive and only 22% HIV-negative clients brought their husbands for counselling. Other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and danger signs of pregnancy were hardly discussed.

| Topic/issues of discussion | Counselling session with woman client alone | Counselling session in the presence of husband* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-negative clients (171) n (%) | HIV-positive clients (30) n (%) | HIV-negative clients (38) n (%) | HIV-positive clients (23) n (%) | |

| Counsellor advised the client to bring husband for next session | 46 (27.0) | 26 (90.0)* | – | – |

| Husband came along with the client during a session | 38 (22.2) | 23 (79.0) | – | – |

| HIV transmission among adults | 132 (77.2) | 24 (80.0) | 38 (100.0) | 23 (100.0) |

| HIV transmission from mother-to-child | 114 (66.7) | 23 (76.7) | 21 (55.3) | 22 (95.7) |

| HIV testing | 3 (1.8) | 3 (10.0) | 2 (5.3) | 3 (13.0) |

| HIV results | 126 (73.7) | 29 (96.7) | 35 (92.1) | 23 (100.0) |

| Other Sexually Transmitted Infections | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Caring during pregnancy | 4 (2.3) | 10 (33.3) | 3 (7.9) | 10 (43.5) |

| Diet during pregnancy or lactation | 11 (6.4) | 10 (33.3) | 9 (23.7) | 10 (43.5) |

| Preparation for delivery | 3 (1.8) | 20 (66.7) | 2 (5.3) | 18 (78.3) |

| Place of delivery | 5 (2.9) | 20 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Danger signs of pregnancy | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Advised on breastfeeding | 19 (11.1) | 22 (73.3) | 6 (15.8) | 20 (87.0) |

| Advised on replacement feeding | 1 (0.6) | 22 (73.3) | 0 (0.0) | 19 (82.6) |

| Advised on family planning | 8 (4.7) | 12 (40.0) | 2 (5.3) | 11 (47.8) |

One participant was a widow.

Details of the issues discussed during counselling on the day of interview.

3.4. Couple counselling

Table 2 reveals that the issues discussed with HIV-positive client couples were similar to those discussed during the individual counselling session focussing on preparation for delivery, breastfeeding and replacement feeding for the child. None of the couples received counselling on other STIs and danger signs of pregnancy.

3.5. Clients’ perception on the counselling services

According to 39% of the HIV-positive and 36% of the HIV-negative clients, consultation time was too short. While 90% of HIV-negative clients did not want to ask questions, 57% of the HIV-positives wanted to ask questions. Privacy during counselling was not ensured, as the individual counselling sessions occurred in the presence of other clients or other healthcare staff at all the centres. A majority (64% HIV-negative and 60% HIV-positive clients) did not receive health education material.

3.6. Details of HIV testing and reception of test results

For 95% of the HIV-negative and 63% of the HIV-positive women, pre-test counselling was not helpful in taking the decision to undergo testing (Table 3). Before undergoing the HIV test, 27% of the HIV-positive women talked to either their husband (17%) or their mother-in-law (10%). One client did not receive any pre-test counselling before undergoing the HIV testing. Table 4 reveals that only 54 (32%) HIV-negative clients and 26 (90%) HIV-positive clients’ husbands accompanied them for counselling. Only 51 (30%) HIV-negative clients’ and 26 (90%) HIV-positive clients’ husband/partner had undergone HIV testing. Regarding the purpose of the visit on the day of the interview, a majority (77% HIV-positive and 85% HIV-negative clients) visited the clinic for medical check-ups and reception of the test results as well (Fig. 2).

Purpose of the visit after HIV test and the reasons for collecting test results.

| HIV-negative clients n (%) | HIV-positive clients n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Not helpful in decision-making to undergo HIV test | 161 (94.7) | 19 (63.3) |

| Helpful in decision-making to undergo HIV test | 9 (5.3) | 11 (36.7) |

| Clients talked to someone else before taking decision to undergo HIV test | 4 (2.4) | 8 (26.7) |

| Persons involved in decision-making to undergo HIV test | ||

| Husband | 3 (1.7) | 5 (16.7) |

| Mother-in-law | 1 (0.6) | 3 (10.0) |

One client reported that she underwent HIV testing without pre-test counselling.

Opinion on the usefulness of pre-test counselling to undergo HIV testing.*

| HIV-negative clients n (%) | HIV-positive clients n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Quality of post-test counselling | ||

| Average | 22 (12.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Good | 128 (74.9) | 23 (76.7) |

| Very good | 21(12.2) | 7 (23.4) |

| Friendly | 105 (61.4) | 3 (10.0) |

| Non-judgmental | 40 (23.4) | 1 (3.3) |

| Supportive | 26 (15.2) | 26 (87.7) |

| Counsellor’s demeanour as elaborated by clients | ||

| Told about HIV | 92 (53.8) | 2 (6.7) |

| Showed good behaviour and manners | 49 (28.7) | 1 (3.3) |

| Solved other problems | 27 (15.8) | 26 (87.7) |

| Cannot say | 3 (1.7) | 1 (3.3) |

| Listening skills of counsellor | ||

| Did not listen | 156 (91.2) | 11 (36.7) |

| Listened to the clients | 15 (8.8) | 19 (63.3) |

| Counsellor’s communication skills | ||

| Easy to understand | 89 (52.1) | 23 (76.7) |

| Difficult to understand | 82 (47.9) | 7 (23.3) |

| Questions during post-test counselling | ||

| Clients had questions | 10 (5.8) | 19 (63.3) |

| Counsellor answered questions | 9 (90.0) | 19 (100.0) |

Opinions and perceptions of clients regarding the post-test counselling services.

Regarding other sources of information about HIV transmission from mother to child, 24% had heard or had seen such information mainly through TV, newspaper, hoardings, pamphlets and healthcare personnel. Family members or friends were other sources of information (17% HIV-negative and 29% HIV-positive women).

3.7. Opinion regarding working hours of the clinic, waiting time and other issues at the clinic

Working hours of the clinic (9 a.m.–12:30 p.m. in all hospitals) were convenient to 90% of the HIV-positive and 67% of the HIV-negative clients. The results were similar with respect to the waiting time at the clinic. When asked to express their opinion regarding any other issues at the clinic, only 140 HIV-negative and 6 HIV-positive clients responded. The doctor did not spend adequate time according to 59% of the HIV-negative clients; 35% felt it was inconvenient to go to too many places within the clinic; and 53% reported overcrowding at the clinic.

3.8. Reception and opinions regarding the pre-test counselling

Only 7 (23.3%) of the HIV-positive and 59% of the HIV-negative clients received group counselling. All of the HIV-positive, but only 49% of the HIV-negative clients received individual counselling. Out of these, the group counselling was felt useful by 58% of the HIV-negative and 57% of the HIV-positive clients. Individual counselling was felt useful by a majority (94%).

3.9. Perceptions regarding quality of the post-test counselling

Table 4 reveals that the quality of post-test counselling was rated as ‘good’ by 77% of the HIV-positive and 75% of the HIV-negative clients. The services are supportive to 88% of the HIV-positive clients, and the counsellor was helpful in solving other problems. Only 10% of the HIV-positive clients, but 61% of the HIV-negative clients reported the counsellor’s demeanour as friendly. Only 3% of the HIV-positive and 29% of the HIV-negative clients reported that the counsellor showed good behaviour and manners. The results indicate a discriminant attitude of the counsellors towards the HIV-positive clients. Regarding the listening skills of the counsellor, 37% of the HIV-positive and 91% of the HIV-negative clients reported that the counsellor did not listen to them. For 77% of the HIV-positive clients, it was easy to understand what the counsellor said, but 23% of the HIV-positive and 48% of the HIV-negative clients felt it was difficult to understand.

The counsellor discussed the issue of disclosure of the test results to someone with 5% of the HIV-negative and 67% of the HIV-positive clients. A majority (83%) of the HIV-positive clients shared their test results, mostly with their husband (76%); parents (8%); and other kin members (4%). Only 16% of the HIV-negative clients shared this information with someone.

3.10. Clients’ unmet needs in the counselling sessions

The unmet needs of the HIV-positive clients include: importance of infant feeding (40%); safety of the baby and ART medicine (33% each); CD4 counts (20%); transmission of HIV (17%); and diet during pregnancy and lactation (3% each). For HIV-negative clients, the unmet needs include: importance of infant feeding (28%), followed by diet during pregnancy (21%), safety of the baby (15%), HIV transmission (13%), window period (12%), precautions to reduce risk of future transmission of HIV (7%), ART medicines (4%) and CD4 count (2%).

3.11. Self-reported impact of the counselling

Table 5 reveals that post-test counselling mainly helped in increasing the knowledge about the HIV transmission. Still, 30% of the HIV-negative and 13% of the HIV-positive clients reported that post-test counselling had not made any difference.

| HIV-negative clients n (%) | HIV-positive clients n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Post-test counselling had not made any difference | 52 (30.4) | 4 (13.3) |

| The points mentioned in the discussion were already known | 6 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Post-test counselling had increased knowledge about HIV transmission | 104 (60.8) | 22 (73.3) |

| Post-test counselling had enabled to take precautions from acquiring HIV infection | 17 (9.9) | 4 (13.3) |

| Came to know about NGOs | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.7) |

| Perceived the importance of HIV test for the husband | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) |

Self-reported impact of the post-test counselling on knowledge and behaviour of clients.

4. Discussion

The counselling sessions focussed on explaining the HIV results, transmission among adults and transmission from mother-to-child. Still, 20%–30% of clients missed the opportunity to know about HIV transmission. More issues were discussed with the HIV-positive clients. Discussion on window period was grossly missed, thus the clients with behavioural risk or those clients whose husbands are at behavioural risk for acquiring HIV had missed the opportunity to learn about window period and to understand the importance of repeat testing for HIV. HIV-positive clients received discussion on: preparation for delivery, place of delivery, breastfeeding and replacement feeding, while these issues were grossly neglected for the HIV-negative clients. A much lower proportion of clients received counselling on care and diet during pregnancy and lactation. The unmet needs of the HIV-positive clients were: importance of infant feeding, safety of the baby and ART medicine. Regarding the quality, post-test counselling services are rated as good by both types of clients, and the services were supportive for the HIV-positive clients; however, the services were not perceived as friendly. Counsellors were helpful in solving the other problems of the HIV-positive clients, and a majority of clients reported that the counselors listened to them and they understood what the counselor told them. Health education material, which would reinforce the messages given and which would be helpful in disseminating health information to the other members of the family, was not provided to a majority of clients. Privacy was not ensured. Clients had to visit too many places to receive services. Pre-test counselling was not helpful in making informed decisions.

Thus, the study highlights existing shortcomings in the content and quality of the PMTCT counselling services in Delhi. One client undergoing HIV testing without pre-test counselling undermines that this aspect of PPTCT has taken place in a ritualistic manner, and the main philosophy of making informed choices/decisions by the clients is grossly neglected. Sastry et al. demonstrated that complex constructs such as informed consent can be conveyed in populations with little education and within busy government hospital settings, and that the standard model may not be sufficient to ensure true informed consent [16]. Group counselling sessions achieve small gains in HIV knowledge, but there is a continued need for ongoing and multifaceted HIV education [17]. Training programmes for counsellors should focus on making the counsellors understand and realize the importance of informed decision-making and how this would translate to improved service reception, active participation and adherence.

Counsellors focussed much on HIV-positive clients. This may be partly due to overcrowding at the clinics and to the attitude that these services are mainly useful for HIV-positive clients. The findings are in consonant with other studies that the services are falling short in delivering a comprehensive package of PMTCT counselling [18–20]. Similar to the present study, Ndubuka et al. [21] reported that 30% of HIV-positive clients missed the opportunity of receiving infant feeding counselling as a part of PMTCT services. Counselling on infant feeding was an important predictor of infant feeding practices [21].

Counsellor’s attitude (in particular, the client feeling “hurried”) might be an indirect outcome of multiple factors like inadequate time, unfriendly attitude of the counsellor, and client’s disinterest in the whole process of PMTCT counselling. There was a gross violation in maintaining privacy and confidentiality, which would lead to long-term adverse effects on the attendance at the clinic and even more so for the high-risk group [20,22]. Lack of two-way communication and a congenial atmosphere during counselling might be an indirect reflection of paucity of time available for post-test counselling, in addition to some other factors like the counsellor’s consultation style and attitudes towards the clients and the service itself. Dissatisfaction with counsellor’s communication may be attributed to the use of more technical words during the counselling session [23,24], and more efforts need to be exerted on improving provider-client communication [25].

The counsellors advised the majority of HIV-positive, but only one fifth of HIV-negative clients for couple counselling as found in other studies [26]. Couple counselling is key to men’s involvement and thereby provides an opportunity for understanding various issues pertaining to HIV, and sexual and reproductive health [27]. Various socio-cultural factors may influence the involvement of the husband in pregnancy and child birth. Comprehensive strategies to sensitize and advocate the importance of the male partner/husband are to be put in place [28] as a part of the training programme.

Other issues like: “the doctor did not give adequate time;” “the clinics were too crowded;” and “they had to go to multiple stations for different reports” are not specific to these services, but are generic to the resource-constrained public-sector hospitals in India [29–31]. Addressing these issues would require a greater allocation of resources, specifically human and infrastructure resources and commitment to attaining the same.

Similar to the present study findings, earlier studies also reported that group counselling had little impact on women regarding HIV prevention and on informed consent for HIV testing [19,32], and post-test counselling is a badly neglected area and emphasized the importance of capacity building of concerned staff [18].

Disclosure of HIV test results to sexual partners is associated with less anxiety and increased social support among many women [33]. HIV risk behaviours and risk behavioural change were dramatically improved among couples where both partners were aware of their HIV [20,26,34]. HIV status disclosure to sexual partners enabled couples to make informed reproductive health choices that ultimately lower the number of unintended pregnancies [20]. In the background of the existing stigma and feared consequences of disclosure, efforts to improve the behaviour of disclosing the HIV status to the sexual partner needs attention.

The present study warrants the need for improving the services through meeting an adequate number of dedicated, well-trained, full-time counsellors depending upon the client load and the provision of adequate space for the counsellors. Refresher training of the counsellors is needed. The refresher training should focus on improving communication skills. Nonetheless, the training component should also focus on attitudinal aspects of the providers and how the discriminant attitude of the provider can have negative consequences on overall goals of the programme. Panditrao et al. [35] emphasized the need for innovative and effective counselling techniques for less-educated women, better strategies to increase the uptake of partner’s HIV testing, and early registration of women in the programme for preventing loss to follow-up in PMTCT programmes. There is a need for focussing on the health education component for better implementation and acceptance by the people. Health education enhances the voluntary counselling and testing uptake in antenatal settings [36]. A nationwide study by the Indian Council of Medical Research also concluded that improved counselling services are required for better case detection [37]. Improved access to counselling and testing facilities and addressing the discriminatory behaviour of healthcare providers are crucial for preventing mother-to-child transmission in India. Better management and supervision of these services would help in monitoring, performance, evaluation and development of skills of the counsellors. Also, further research is needed to gain an in-depth understanding of the counsellors-related factors. This would lead to design of appropriate service delivery through which the objectives of the PMTCT programme are met.

The study has certain limitations, such as only post-test counselled women were included and drop-out clients could not be interviewed. Thus, these results may have an element of over-reporting of the satisfaction of clients with the counsellors because those most severely dissatisfied with the pre-test counselling might not have returned for post-test counselling. Efforts to follow-up women who are not continuing with the services may give better insights into the healthcare-seeking behaviour of women, particularly those at risk. The sampling process was not based on probability sampling. Despite these limitations, the study was able to capture various categories of women pertaining to HIV status, selected from 50% of the tertiary care hospitals providing these services in Delhi. This ensures that the results are reliable and are useful for further improvements in the service.

Declaration of interests

No competing interests to declare.

Funding

This research did not receive any funding.

Contributorship

All authors have contributed to this publication and hold themselves responsible for the content of the paper.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Arvind Kumar AU - Bir Singh AU - Yadlapalli S. Kusuma PY - 2015 DA - 2015/01/16 TI - Counselling services in prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) in Delhi, India: An assessment through a modified version of UNICEF-PPTCT tool JO - Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health SP - 3 EP - 13 VL - 5 IS - 1 SN - 2210-6014 UR - https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jegh.2014.12.001 DO - 10.1016/j.jegh.2014.12.001 ID - Kumar2015 ER -