Cross-border Collaboration to Improve Access to Medicine: Association of Southeast Asian Nations Perspective

- DOI

- 10.2991/jegh.k.190506.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Cost comparisons; affordability; medicine pricing; health care economics and organizations; cost control

- Copyright

- © 2019 Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 30% of the global population, mainly in low-income countries, is deprived of regular access to essential medicines. A WHO study on pricing approaches and their impacts on availability and affordability of cancer drugs revealed that cancer drugs prices have been manipulated, causing limited access to those in need [1]. This is also particularly true for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). About 58% of the total hypertensive population and 52% of the total diabetic population in Cambodia went untreated, possibly due to the difficulties in accessing or paying for treatment [2]. Purchasing-power-parity-adjusted mean unit prices of the originator cancer drugs bortemozib (3.5 mg vial) costs US$ 3622.22 in Malaysia and US$ 4630.12 in Thailand, whereas sunitinib malate (12.5 mg capsule) costs US$ 150.47 in Malaysia and US$ 89.2 in Thailand [3]. Therefore, access to medicines has become a global issue and the WHO has prioritised this agenda in the Sustainable Development Goals as one of the focuses in the pursuit of universal health coverage [4]. Affordability and availability of medicines are two of the key determinants of access, in both public and private sectors [5].

2. AFFORDABILITY AND AVAILABILITY OF MEDICINES

Association of Southeast Asian Nations, a regional intergovernmental organisation established in 1967, has positioned itself as an important platform for economic, political, and sociocultural cooperation and integration. ASEAN comprises 10 member countries, namely, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, and Brunei. ASEAN is committed to improving access to health services for its communities with the establishment of ASEAN Strategic Framework on Health Development (2010–2015), reaffirming member countries commitments to the WHO 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The rapid advancement in medical technology has brought large benefits but also contributes to the increased health spending, which is out-of-reach of patients and governments alike. Between 2000 and 2010, ASEAN countries have seen an increasing trend of average annual growth rate in pharmaceutical spending per capita. Most ASEAN countries reported an average annual growth rate of above 6% with the exception of Brunei and Cambodia, registering a minimal growth rate of below 6% [6]. New and innovative health technologies have made the prices of medicines unjustifiably high and beyond the reach of the majority of the population.

A 2009 medicine price survey in the Philippines indicated that the public sector procured originator brand medicines at 26.33 times higher than the international reference prices, while the generics were procured at 7.97 times higher. Furthermore, the survey found poor affordability of the lowest-price generics in the public sector, whereby the standard treatment for most conditions cost more than 75% of a days’ wages [7]. Similarly, a 2005 price survey in Vietnam showed public procurement price for originator brand medicines were 8.29 times the international reference prices and 1.82 times the international reference prices for the lowest-price generics. Medicines in Vietnam are generally unaffordable, ranging from 0.7 days’ wages to obtain generic amoxicillin for acute respiratory infection treatment to 15.9 days’ wages for generic ceftriaxone in the public sector [8].

In the Philippines, 15 key medicines used for the treatment of common health conditions was found to be available only in 53.3% of the public health facilities. If the list is expanded to include medicines used to treat the most common causes of morbidity as recommended by WHO, the availability of generic and originator brand medicines were lower, at 27.5% and 8% of the public health facilities, respectively. Stock out duration in Philippine’s public health pharmacies was reported at 24.9 days and 43.8 days in the central-district warehouses [7]. Malaysian patients have alleged the lack of availability of certain cancer medicines (i.e., sunitinib) in the national formulary, forcing them to make exorbitant out-of-pocket payments that may lead to financial catastrophe [9].

3. CROSS-BORDER COLLABORATION

Cross-border collaboration efforts are not a new strategy to improve access to medicines. Previous experience of collaboration efforts between the public and private sector has achieved remarkable results, through international organisations such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM), the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, UNITAID, and Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance. In recent years, more governments have come to a realisation that they stand a better chance to obtain better pricing and procurement terms as a joint network when dealing with drug manufacturers. Many years ago, such regional cooperation seemed inconceivable due to the fragmented and diverse nature of the healthcare system in individual countries. However, recent developments such as the creation of Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Austria (BeNeLuxA) in 2015 (with Austria joining in June 2017), an intergovernmental regional collaboration between BeNeLuxA, have led to joint negotiations and information sharing. Following in the footsteps of BeNeLuxA, the Southern Mediterranean EU countries of Italy, Spain, Portugal, Malta, Cyprus, and Greece signed the Valletta Declaration in May 2017 to jointly negotiate with the pharmaceutical industry on drug pricing and exchange of information. A regional network of Central European countries, namely the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia formed the Visegrád Group to jointly purchase medicines for rare diseases.

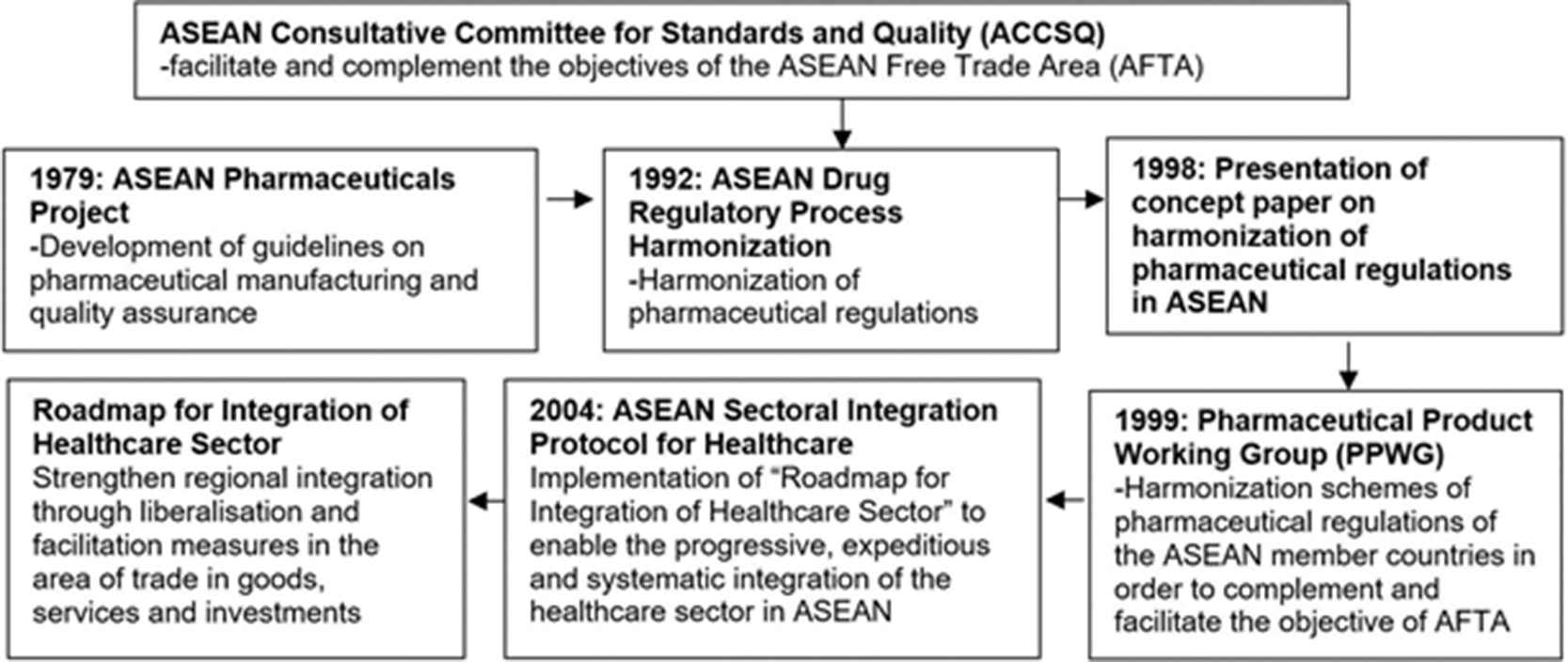

In 1979, ASEAN member countries adopted a broad framework known as the ASEAN Pharmaceuticals Project. Over the years, this collaboration has resulted in the development of several important milestones and integration of guidelines on pharmaceutical manufacturing and quality assurance, as shown in Figure 1.

Milestones of Association of Southeast Asian Nations Consultative Committee for Standards and Quality (ACCSQ) and Pharmaceutical Product Working Group (PPWG)

In 1999, with the formation of Pharmaceutical Product Working Group (PPWG), harmonization of pharmaceutical regulations in ASEAN gained more traction. ASEAN Consultative Committee for Standards and Quality (ACCSQ)–PPWG is the main corresponding body in achieving accessibility of quality, safe, and efficacious products in the ASEAN region. The PPWG, over the years, has achieved various milestones, for instance [10,11]: (1) December 2005: feasibility study of an ASEAN Mutual Recognition Arrangement for pharmaceutical/medicinal products was completed; (2) December 2005: feasibility study of implementing a twinning system, where one member country could bridge the regulatory capacity and resource development voluntarily with another member country; (3) December 2005: postmarketing alert system was formalised for defective and unsafe pharmaceutical/medicinal products; (4) March 2006: labelling standards for pharmaceutical/medicinal products were harmonised; (5) January 2007: feasibility study of adopting a harmonised placement system for pharmaceutical/medicinal products into the ASEAN markets was initiated; and (6) December 2008: ASEAN Common Technical Dossier was implemented.

Nevertheless, the harmonisation efforts are seen as effective tools to facilitate the pharmaceutical trade in the region but offer less consideration to improve access to medicine. Leveraging on the success of harmonisation, regional cooperation and collaboration can provide practical solutions to make medicine more accessible. For example, the success of Pharmaceutical Inspection Cooperation Scheme among the signatories has paved the way for harmonisation of product registration and labelling.

In addition, high population mobility from ASEAN across the countries was reported; for example, the share of total migrants to Singapore and Malaysian population is 29.3% and 9.45%, respectively [12]. Unofficial findings, taking into account the undocumented migrants, show that the percentage of foreign workers is estimated to be 20% of the Malaysian population [13]. Therefore, ASEAN large population and geographically close proximity of member countries, and expanding global opportunities in pharmaceutical trade provide good leverage to implement cross-border collaboration, improving access to medicines and ultimately to contain pharmaceutical expenditure.

Strategic areas for collaboration may include the following.

3.1. Establishing a Regional versus Centralised Pooled Procurement System

Globally, medicines are priced differently in each country based on the countries capacity and negotiating power. Purchasing countries with a small population or rare conditions with limited targeted populations have low bargaining power and are subjected to higher reference pricing [14]. The establishment of regional procurement systems enables ASEAN member countries to achieve joint negotiation and pooled procurement, and creates an economy of scale, resulting in significant cost savings and efficiency. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) model that consists of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates serves as a good role model for ASEAN. GCC coined the idea of establishing a group purchasing programme for pharmaceuticals and medical supplies in 1976 [15]. The GCC started with 32 items worth US$ 1 million, and the group purchasing programme currently contains >7000 items valued in excess of US$ 600 million. Since its inception, the programme has achieved >30% cost savings [16].

The bulk ordering and negotiation made collectively under the ASEAN umbrella for a population of >622 million could be advantageous. However, one needs to take a cue from other multinational organisations such as the United States Agency for International Development and GFATM. For example, although it was opposed initially due to lack of autonomy by the health authorities of the member countries, the logistic application and implementation for GFATM in Benin, Ethiopia, and Malawi was managed using a centralised approach. Impartiality in decision-making was also crucial because their health decision-making was decentralised to provide personalised planning of HIV/AIDS activities.

To overcome the challenges of product fraud and supply chain issues, a harmonised effort towards joint regional rather than centralised pooled procurement will ensure that each country manages its own inventory and supply chain, thus bringing the shared benefit of better pricing mechanisms. In this way, an independent vertical system for each member country is applied to facilitate the control of commodity security and distribution coordination at the country level.

This is because an integrated approach to ensure the commodity security across >4.5 million km2 of land within the ASEAN region could entail an enormous amount of programme coordination. This is further complicated by the customs and bureaucratic issues because medicinal products are not exempted from cross-border movement.

3.2. Establishing Mechanism for Information Sharing

Information asymmetry in medicine procurement and pricing has hindered the ability of governments to make efficient decisions and improves access to medicines. Governments are engaged with pharmaceutical companies in numerous types of managed-entry agreements and confidential rebates that hamper the use of reference pricing mechanisms. Such confidentiality actually undermines their negotiating power and does not guarantee lower prices [17]. Therefore, mechanisms to collect and exchange information are crucial to inform policymakers for decision-making processes. Information such as costs, pricing, and patent information should be collected and exchanged freely among ASEAN member countries. However, the current publicly available medicines price information among ASEAN countries is limited and compiled individually by respective countries in their national languages, making price comparison a daunting task. It is noteworthy that in 2009, the WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific initiated the Price Information Exchange for Essential Medicines (PIEMEDS) (www.piemeds.com); an information sharing platform that contains medicine prices procured by the public sector. However, due to the voluntary reporting nature of the system that leads to poor response from member countries, potential benefits of PIEMEDS have not been optimised. Data in PIEMEDS were found to be outdated with limited coverage of medicine types, merely comprising the WHO EMEDS List. In addition, PIEMEDS does not capture data from all ASEAN member countries due to the fact that Indonesia, Myanmar, and Thailand are not part of WHO Western Pacific Region. Nevertheless, the entity of ASEAN is in a unique position to absorb and use the lessons and recommendations from PIEMEDS because of its complementary nature.

3.3. Establishing Regional Joint Horizon Scanning

Horizon scanning is the systematic identification of new and emerging health technologies that have a potential impact on health and budgetary impact on health systems [18]. Horizon scanning is seen as the starting point of medicines accessibility [19]. In most ASEAN countries, horizon scanning is still in its infancy [20]. A quick check on Malaysian Ministry of Health website (www.moh.gov.my) showed only 11 horizon scanning reports produced to date. The establishment of joint horizon scanning will avoid duplication of efforts and reduce the resources needed from government [21]. Two possible areas of horizon scanning for ASEAN member countries to jointly carry out are the identification and filtration processes. Identification involves screening of new medicines that potentially enter the ASEAN market within the defined time horizon, while filtration selects products that are relevant to the country-specific needs, prior to the gathering of more in-depth data.

4. MEASURES TO FACILITATE CROSS-BORDER COLLABORATION IN ASEAN

The development of cross-border collaboration is complicated and a difficult journey, involving various players from a diverse background with varied goals and objectives. Collaboration has to be worthwhile and achieves significant cost savings, efficiency, and other benefits, or otherwise, it will not materialise. Therefore, an understanding of how to work within the ASEAN structure is important for a successful cross-border collaboration. Approaches that can be taken to prepare a conductive platform for cross-border collaboration are as follows.

- (1)

Comprehensive understanding of healthcare system in each ASEAN member country. Countries with similar healthcare systems and contextual factors (population size and profile, geographical position, and disease burden) tend to achieve better collaboration. Multilateral discussion and framework agreements at international level can overcome such differences.

- (2)

Establishing a roadmap for cross-border collaboration to guide member countries on clear, concrete steps to engage policy stakeholders in their respective countries. The roadmap should have common elements that are relevant to all member countries, yet individual countries can have their own national plan in implementing cross-border collaboration.

- (3)

Formulating a legal framework for cross-border collaboration. Perhaps, the single most important barrier to a successful collaboration is the legal uncertainties. ASEAN member countries have different political and legal structures, thus it is vital to find a common path to institutionalise these differences before a functional framework agreements can be adopted.

- (4)

Harmonising the procurement system, information collection, and reporting methodology. Harmonisation of procurement systems and procedures, along with the criteria for prequalification of manufacturers, suppliers, and medicines are necessary. Furthermore, for any information to be beneficial, standardisation of methodology such as costing, measurement, selection of medicines, time horizons (for horizon scanning), and reporting techniques will bring better chance of successful collaboration.

- (5)

Strengthening of political will. The presence of political will is necessary to begin the process of change. The ASEAN network and commitments can be the international drivers of change, highlighting the challenges in medicines access. Leaders of member countries need to champion the issues and give the continuous commitment, thus translating these commitments into sustainable actions.

The PPWG may also undertake a nonvoluntary acquisition of the pharmaceutical patents pursuant to individual federal statutory authority, which could lower procurement costs by >90% [22]. Another aspect that the pharmaceutical regulatory agencies should consider is an online logistics management information network system connecting all member countries. This network system would be useful to track the payment and distribution of pharmaceutical products including the cold chain, controlled narcotics, etc. [23].

5. CONCLUSION

Cross-border collaboration is often put forward as a crucial strategy for improving health outcomes; therefore, it should be tabled for discussion at the next ASEAN summit. The ASEAN trades and health ministers could emulate the development of ASEAN Sectoral Mutual Recognition Arrangement on Good Manufacturing Practice Inspection, which facilitates the ASEAN cross-border movement of pharmaceutical products by mutual exchange and recognition of Good Manufacturing Practice certifications. Furthermore, the presenting ministers of the ASEAN Sectoral Integration Protocol for Healthcare, as advised by PPWG, should further ratify the agreement to ensure ASEAN communities have access to medicines, by making needed medicines available and affordable.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Kah Seng Lee AU - Long Chiau Ming AU - Qi Ying Lean AU - Siew Mei Yee AU - Rahul Patel AU - Nur Akmar Taha AU - Yaman Walid Kassab PY - 2019 DA - 2019/06/11 TI - Cross-border Collaboration to Improve Access to Medicine: Association of Southeast Asian Nations Perspective JO - Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health SP - 93 EP - 97 VL - 9 IS - 2 SN - 2210-6014 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.190506.001 DO - 10.2991/jegh.k.190506.001 ID - Lee2019 ER -