Knowledge, Attitude and Practice toward COVID-19 among Egyptians

- DOI

- 10.2991/jegh.k.200909.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- COVID-19; knowledge; attitude; practice; Egyptians

- Abstract

COVID-19 is a public Health Emergency of International Concern. The aim of this work was to assess the level of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (KAP) among Egyptians toward COVID-19. A cross-sectional study was conducted from March 1st to April 1st, on 3712 participants of different ages and sex. An author designed KAP questionnaire toward COVID-19 administered online and personally was delivered. Satisfactory knowledge, positive attitude and good practice were reported among 70.2%, 75.9% and 49.2% of the participants respectively. Middle-aged participants reported high knowledge and attitude levels with poor practice level (p < 0.001). Females reported high knowledge and practice levels and low attitude (p < 0.001 and p = 0.041 respectively). Despite reporting high knowledge and attitude among urban residents (p < 0.001), practice level was high among rural residents (p = 0.001). Post-graduate education reported the highest levels of KAP (p < 0.001). Rural residents, working and non-enough income participants reported lower level of practice (p < 0.001). Logistic regression was carried out. It was found that unsatisfactory knowledge was associated with low education [Odds Ratio (OR) = 1.97, 95% CI: 1.51–2.56], and of rural residency (OR = 1.2, 95% CI: 1.05–1.41). Negative attitude was associated with not working (OR = 1.94, 95% CI: 1.61–2.35) and not enough income (OR = 1.29, 95%CI: 1.10–1.51 respectively). Poor practice is associated with young age (OR = 2.41, 95% CI: 1.94–2.98) and low education (OR = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.03–1.37) and not working (OR = 4.95, 95% CI: 4.07–6.02). Satisfactory knowledge, positive attitude and poor practice were found among the participants. A good knowledge and lower practice level were found among middle-aged, working participants, and participants with insufficient income. The demographic characters associated with KAP could be the cornerstone in directing policy-makers to target the health education campaigns to the suitable target groups.

- Copyright

- © 2020 The Authors. Published by Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention officially announced a novel coronavirus as the causative pathogen of COVID-19 on 8th of January 8, 2020 [1]. COVID-19 epidemics started from Wuhan city last December, and on the 30th of January 2020, World Health Organization (WHO) declared that COVID-19 is a public Health Emergency [2]. This disease was named as COVID-19 by the WHO, and the causative virus was named as SARS-CoV-2 by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses [3]. This problem started as a single animal-to-human transmission in Wuhan [1], and was followed by continued human-to-human spread [4]. Sustained local transmission of the disease all over the world led the WHO to declare COVID-19 as a pandemic [5]. The Incubation Period (IP) of COVID-19 is about 1–14 days [6], and the period from the onset of symptoms to death was estimated to range from 6 to 41 days [7]. Interpersonal transmission of COVID-19 occurs through respiratory droplets and contact transmission [8]. As the SARS-CoV-2 was found in stool of patients from China and the United States, there is a risk of fecal-oral transmission [9]. The sources of infection are patients with symptomatic COVID-19 and asymptomatic patients and patients in IP who are carriers of SARS-CoV-2 [4]. According to a study done in Wuhan city, the most common symptoms of COVID-19 were fever, fatigue, dry cough, myalgias, and dyspnea. Of the confirmed cases, 81% suffered mild to moderate disease, 14% suffered severe disease, and only 5% suffered critical illness, with an overall case fatality rate ranging from 2.3% to 5%. Recovery in mild cases occurred after 1 week, while in severe cases, death may be the fate [10]. Those who were at a higher risk for severe illness and death were patients with age >60 years and those having pre-existing diseases as hypertension, diabetes, etc., [4].

On the 14th of February 2020, Egypt reported its first confirmed COVID-19 case as the first reported case in Africa [11]. In late February and early March, multiple foreign COVID-19 cases associated with travel to Egypt were reported. [12] On the 16th of March, the minister of aviation decided to close the airport [13]. On the 19th of March, a decision was taken by the Egyptian government to close all restaurants, cafes, nightclubs and public places from 7 pm until 6 am [14], and on the 21th of March prayers were suspend in all Egypt’s mosques [15]. On the 25th of March, a team of WHO experts concluded a COVID-19 technical support mission to Egypt then a WHO Regional Office and mission team lead “considerable efforts are made to control COVID-19 outbreak in the fields of early detection, laboratory testing, isolation, contact tracing and referral of patients [16].

Knowledge and attitudes toward infectious diseases are associated with level of panic emotion among the population, which can further complicate attempts to prevent the spread of the disease. The work aimed to assess the level of knowledge, attitude and practice among Egyptians toward COVID-19.

2. SUBJECTS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional study was conducted from March 1st to April 1st, the week immediately after the cases started to emerge in Egypt. Approval of local ethical committee was obtained. The tools of this work involved a questionnaire consisting of two parts: (i) Demographics data included age, gender, education, occupation, residence and income. We did not take marital status into account as the study was distributed to include children younger than 18 years old. (ii) Knowledge, attitude and practice toward COVID-19. The knowledge part had 15 questions: six for clinical presentations, mode of transmission and at-risk people (K1–K6), eight for management of COVID-19 (K7–K14), and one for sources of information. These questions were answered on a Yes/No basis with an additional “I don’t know” option. There are four inverse questions (Is there a vaccine for COVID-19? Seasonal influenza vaccine can be used against COVID-19?, Is there a treatment for COVID-19? and Is COVID-19 patients can be treated at home?). The points were distributed as (Yes = 2, No = 1 and I don’t know = 0) except for the inverse questions whereas (Yes = 1, No = 2 and I don’t know = 0). The total knowledge score ranged from 0 to 30, with a higher score denoting a better knowledge of COVID-19. The attitude part had seven questions (R = 0–14) and practice part included nine questions (R = 0–18), with at least 80% correct answers were considered as having satisfactory knowledge. Participants with at least 80% positive answers were considered as having a positive attitude and good practice. To avoid inter and intra-observer bias, the data collecting team (three physicians and five civilian individuals) received training on the questionnaire for 3 h followed by testing to assess the preparedness and the quality of the asking and reporting.

The work was conducted on two steps:

- (1)

A Pilot study was conducted to 50 participants (30 direct interview participants and 20 online participants) of different age and sex to assess the questionnaire adequacy for language, contents, and time and to explore the potential obstacles and difficulties that confront the execution of the work in addition to any differences between online and direct response to the interviewers. Reliability of the questionnaire was tested and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the knowledge questionnaire was 0.73 [17]. To the best of our knowledge, no published research reported the level of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (KAP) about COVID-19 among Egyptians, so it is estimated that level of KAP equal to level of no KAP (p = q = 0.5) and with acceptable limit of precision (D) of 0.015 value, the sample size was estimated to be 3518 participants.

- (2)

A convenience sampling technique was applied. Online and google forms besides personal contacts were used to collect the data especially after the legal procedures taken by the authorities to take care against disease transmission. The questionnaire was distributed to people of different age, sex, occupation and socio-economic standard to have real response. It was not possible and right to stand on online forms only as the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics [18] in Egypt announced that Egypt’s illiteracy rate was 25.8% in 2017. So it was not accepted to depend on the online questionnaire alone as it will address not only the educated individuals but also those who know how to deal with online questionnaire so direct administered questionnaire was inevitable. Egyptian aged 12–82 years, understood the content of the questionnaire, and agreed to participate in the study were eligible persons to share in the study via clicking the link or filling in the printed questionnaire. The online form of the questionnaire was distributed giving back of 794 questionnaires. The involved team bedside the authors delivered personally 3026 questionnaires. Incomplete questionnaires (n = 108) were excluded from the printed questionnaires giving back 2918 complete printed questionnaires distributed as (1) Hospitals: n = 1565 participants; five large hospitals (two governmental and three private). (2) Working people: n = 837 participants in governmental (n = 4) and non-governmental (Private sector) buildings (n = 5) (Highly employed rate buildings were enlisted then the studied buildings were chosen randomly). (3) Banks: The highest flow rate was in three Banks; n = 516 participants). The total collected questionnaires were 3820 (3026 printed copy and 794 online forms collected via google form link sent through mails and social media). The final total number was 3712 (2918 printed and 794 online) questionnaires with a response rate of 97.2%.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

Results were statistically analyzed by SPSS version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Independent t-test was used to compare two means of normally distributed data. ANOVA (F-test) was used for parametric data to compare more than two means. Binary logistic regression analysis was done, which analyses independent predictors with Odds Ratios (ORs) for a binary outcome. p-value was considered significant if <0.05.

3. RESULTS

A cross-sectional study was conducted on 3712 participants aged (23.31 ± 13.28, R = 12–82), distributed as males 47.8% and 52.2% females. Participants in rural residence represented 48.8%. The education level was distributed between basic education and post-graduate education, 36.9% and 2.3% respectively. The non-working participants represented the major percentage of 61.1%. About 41.1% of the participants reported that they have no enough income (Table 1). There was difference between the printed questionnaires (n = 2918) and online questionnaires (n = 794) regarding age, sex and residence where young ages, females and urban residents tended to respond more to the online forms.

| Demographic data | N = 3712 | |

|---|---|---|

| No | % | |

| Age (Years) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 23.31 ± 13.28 | |

| Range | 12–82 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1773 | 47.8 |

| Female | 1939 | 52.2 |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 1811 | 48.8 |

| Urban | 1901 | 51.2 |

| Education | ||

| Basic | 1368 | 36.9 |

| Secondary | 1171 | 31.5 |

| University | 1089 | 29.3 |

| Post-graduate | 84 | 2.3 |

| Occupation | ||

| Working | 1445 | 38.9 |

| Not working | 2267 | 61.1 |

| Sector of occupation (n = 1445) | ||

| Governmental | 572 | 38.7 |

| Private | 907 | 61.3 |

| Income | ||

| Enough | 2162 | 58.2 |

| Not enough | 1550 | 41.8 |

Demographic data of the studied groups

All participants heard about COVID-19 and all of them reported that it is a viral infection. There was variation in mode of transmission, where 96.5% reported that it can be transmitted by cough or sneezing while some participants also reported that it can be transmitted by infected meat (8.8%) or parenteral (23.5%). The main symptom was fever to be reported by 97.7%. Old people were the main at risk category with a percentage of 75.9%. Regarding the availability of vaccine and if seasonal flu vaccine could be used for prevention most of the participants reported that there is no available vaccine and seasonal flu vaccine could not be used for prevention of COVID-19 (Table 2).

| Knowledge | No | % | No | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you heard about COVID-19 | 3712 | 100.0 | Is there a vaccine for COVID-19? | ||

| Cause of COVID-19: | Yes | 56 | 1.5 | ||

| Virus | 3712 | 100.0 | No | 3512 | 94.6 |

| Bacteria | – | – | I don’t know | 144 | 3.9 |

| Parasites | – | – | Seasonal influenza vaccine can be used against COVID-19 | ||

| Immune deficiency | – | – | Yes | 96 | 2.6 |

| I don’t know | – | – | No | 3420 | 92.1 |

| Mode of transmission: | I don’t know | 196 | 5.3 | ||

| Cough and sneezing | 3581 | 96.5 | Is there a treatment for COVID-19? | ||

| Parenteral | 872 | 23.5 | Yes | 168 | 4.5 |

| Meat and milk | 328 | 8.8 | No | 3448 | 92.9 |

| Infected hands | 1464 | 39.4 | I don’t know | 96 | 2.6 |

| Infected surfaces | 1563 | 42.1 | Does isolation of cases helps be treated | ||

| I don’t know | 44 | 1.2 | Yes | 3544 | 95.5 |

| Symptoms of COVID-19: | No | 112 | 3.0 | ||

| Fever | 3628 | 97.7 | I don’t know | 56 | 1.5 |

| Dry cough and difficult breathing | 320 | 86.4 | Is COVID-19 patients can be treated at home | ||

| No fever | 1368 | 36.9 | Yes | 108 | 2.9 |

| Diarrhea | 968 | 26.1 | No | 3468 | 93.4 |

| Incubation period: | I don’t know | 136 | 3.7 | ||

| <2 days | 64 | 1.7 | How to prevent COVID-19* | 3712 | 100.0 |

| 2–14 days | 3268 | 88.0 | Sources of information: | ||

| >14 days | 380 | 10.2 | TV | 1304 | 35.1 |

| At risk people | Social media | 3000 | 80.8 | ||

| Old people | 2816 | 75.9 | Friends | 376 | 10.1 |

| Patients with chronic diseases | 1292 | 34.8 | Physicians | 235 | 6.3 |

| Immuno-deficient patients | 752 | 20.2 | |||

| Travelers to infected regions | 472 | 12.7 | |||

| Pregnant women | 452 | 12.2 | |||

| Contacts of infected cases | 1592 | 42.9 | |||

| I don’t know | 768 | 21.2 | |||

| Is COVID-19 infectious | 3712 | 100.0 | |||

| Is early diagnosis essential to decrease complications | |||||

| Yes | 3584 | 96.6 | |||

| No | 52 | 1.4 | |||

| I don’t know | 76 | 2.0 | |||

Hand washing with soap and water, disinfection of hands with alcohol, avoid touching eyes and nose, avoid contact with infected patients.

Knowledge of the studied groups (N = 3712) about COVID-19

About 99.6% of the participants saw that crowding is behind the intense transmission of COVID-19 and 88.3% of them saw that the country instructions are not enough. While 36.5% of the participants thought that the disease will be contained soon but about 54.8% reported that they do not know the fate and 95.8% reported their fear. About 8.1% of the participants do not know if they are infected or not. About 83.3% of the participants saw that the best behavior when feeling sick is to consult the physician in his clinic and not by phone. The results shows that despite 70.8% of the participants stay at home, about 79.2% of the go to crowding places and 82.3% wear masks (Table 3).

| Attitude | N = 3712 | Practice | N = 3712 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | ||

| Do you think COVID-19 infection increases in crowding and gatherings | Are you infected with COVID-19 | ||||

| Yes | 3696 | 99.6 | No | 3412 | 91.9 |

| No | 4 | 0.1 | I don’t know | 300 | 8.1 |

| I don’t know | 12 | 0.3 | Do you have Infected relatives know a coming person from an infected country | ||

| Do you think Health education can protect against COVID-19 | No | 3712 | 100.0 | ||

| Yes | 3592 | 96.8 | Best behavior when feeling sick | ||

| No | 68 | 1.8 | Consult physician by telephone | 402 | 10.8 |

| I don’t know | 52 | 1.4 | Consult physician in clinics | 3098 | 83.5 |

| Do you think disinfection of the public and buildings protect against COVID-19 | Stay at home | 161 | 4.3 | ||

| Yes | 3592 | 96.8 | Go to emergency hospital | 51 | 1.4 |

| No | 64 | 1.7 | Have you heard about the preventive measures of COVID-19? | ||

| I don’t know | 56 | 1.5 | Yes | 3712 | 100.0 |

| Do you know the country instructions taken to limit the spread of COVID-19* | Are you practicing social distancing of 1.5 m | ||||

| Yes | 3712 | 100.0 | Yes | 2544 | 68.5 |

| Do you think the country instructions are enough | No | 1168 | 31.5 | ||

| Yes | 432 | 11.6 | Are you staying at home these days | ||

| No | 3276 | 88.3 | Yes | 2629 | 70.8 |

| I don’t know | 4 | 0.1 | No | 1083 | 29.2 |

| Do you think that all people committed to these instructions | Are you practicing hand hygiene | ||||

| Yes | 68 | 1.8 | Yes | 3712 | 100.0 |

| No | 3500 | 94.3 | Last days did you go to crowding places | ||

| I don’t know | 144 | 3.9 | Yes | 2940 | 79.2 |

| Do you think that COVID-19 will be contained soon? | No | 772 | 20.8 | ||

| Yes | 1352 | 36.4 | Last days have you ever worn a mask | ||

| No | 324 | 8.7 | Yes | 3056 | 82.3 |

| I don’t know | 2036 | 54.8 | No | 656 | 17.7 |

| Are you afraid of COVID-19? | |||||

| Yes | 3556 | 95.8 | |||

| No | 156 | 4.2 | |||

The country instruction includes curfew, limited working hours, avoidance of overcrowdings and gatherings and closure of all shops after 7 am.

Attitude and practice of the studied groups toward COVID-19

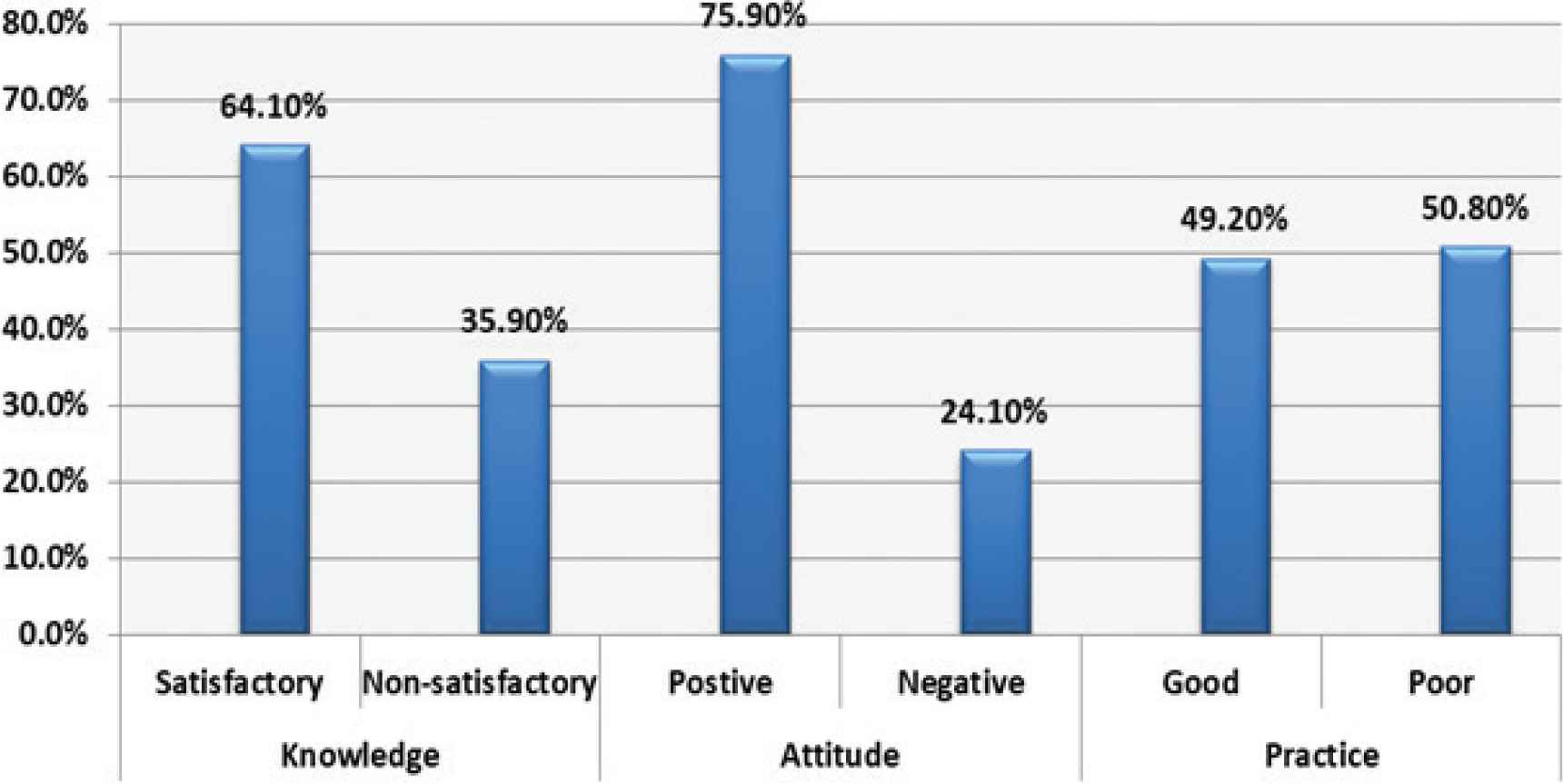

Satisfactory knowledge was reported among 70.2%, positive attitude was reported among 75.9% and good practice was reported among 49.2% (Figure 1).

Knowledge, attitude and practice among the studied participants.

The results show that middle age from 19 to 35 years old reported high knowledge and attitude levels and lower practice level in comparison to lower or higher ages (p < 0.001). Females reported the higher knowledge and practice levels and lower attitude in comparison to males (p < 0.001 and p = 0.041 respectively). Despite reporting higher knowledge and attitude among urban residence (p < 0.001), practice level was higher among rural residence (p = 0.001). Post-graduate education reported the highest levels of knowledge, attitude and practice (p < 0.001). Working participants reported higher level of knowledge (p = 0.023) and lower level of practice (p < 0.001). Also, the private working sector participants reported higher level of knowledge (p = 0.023) and lower level of practice (p < 0.001). Although non-enough income participants reported higher level of knowledge (p = 0.033), they reported a lower level of attitude and practice (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

| Demographic data | Knowledge | Attitude | Practice | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | p-value | Mean ± SD | p-value | Mean ± SD | p-value | |

| Age | ||||||

| 12–18 | 20.94 ± 2.11 | 53.36 | 10.80 ± 1.13 | 81.05 | 13.06 ± 1.09 | 26.66 |

| 19–35 | 21.54 ± 1.25 | <0.001* | 11.0 ± 1.09 | <0.001* | 12.4 ± 1.07 | <0.001* |

| >35 | 20.58 ± 2.79 | 10.22 ± 1.79 | 13.21 ± 1.05 | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 20.83 ± 2.21 | 6.46 | 10.90 ± 1.10 | 6.26 | 12.98 ± 1.06 | 2.04 |

| Female | 21.27 ± 1.89 | <0.001* | 10.64 ± 1.42 | <0.001* | 13.05 ± 1.10 | 0.041* |

| Residence | ||||||

| Rural | 20.88 ± 2.21 | 5.41 | 10.69 ± 1.32 | 3.52 | 12.98 ± 1.06 | 5.75 |

| Urban | 21.24 ± 1.90 | <0.001* | 10.84 ± 1.25 | <0.001* | 12.92 ± 1.0 | <0.001* |

| Education | ||||||

| Basic | 21.21 ± 1.25 | 5.62 | 10.86 ± 1.03 | 12.65 | 13.06 ± 1.13 | 5.56 |

| Secondary | 21.04 ± 2.33 | 0.001* | 10.61 ± 1.49 | <0.001* | 12.92 ± 1.02 | 0.001* |

| University | 20.88 ± 2.58 | 10.76 ± 1.33 | 13.04 ± 1.08 | |||

| Post-graduate | 21.33 ± 0.47 | 11.29 ± 1.11 | 13.26 ± 1.16 | |||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Working | 21.16 ± 2.12 | 2.27 | 10.77 ± 1.36 | 0.40 | 12.82 ± 1.11 | 8.88 |

| Not working | 21.0 ± 2.02 | 0.023* | 10.76 ± 1.24 | 0.689 | 13.14 ± 1.05 | <0.001* |

| Sector of occupation | ||||||

| Governmental | 21.02 ± 2.06 | 1.86 | 10.74 ± 1.64 | 0.65 | 13.07 ± 1.17 | 6.64 |

| Private | 21.24 ± 2.15 | 0.059 | 10.79 ± 1.16 | 0.511 | 12.67 ± 1.04 | <0.001* |

| Income | ||||||

| Enough | 21.0 ± 2.17 | 2.13 | 10.77 ± 1.22 | 7.22 | 13.11 ± 1.10 | 6.04 |

| Not enough | 21.15 ± 1.90 | 0.033 | 10.06 ± 1.38 | <0.001 | 12.89 ± 1.05 | <0.001* |

Significant.

Distribution of the studied participants’ demographic data regarding scores of knowledge, attitude and practice toward COVID-19

A logistic regression was performed to ascertain the effects of age, sex, residence, education, occupation and income on the likelihood that participants may have poor knowledge, negative attitude or poor practice. For knowledge, the logistic regression model was statistically significant, χ2 = 43.36, p < 0.001. The model explained 19.0% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in unsatisfactory knowledge and correctly classified 72.4% of cases. It was found that unsatisfactory knowledge was associated with low education (OR = 2.69, 95% CI: 1.96–3.67), and of rural residency (OR = 2.10, 95% CI: 1.79–2.46). For attitude, the logistic regression model was statistically significant, χ2 = 284.82, p < 0.001. The model explained 5.0% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in negative attitude and correctly classified 75.9% of cases. Negative attitude was associated with not working (OR = 1.94, 95% CI: 1.61–2.35) and not enough income (OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.10–1.51 respectively). For practice, the logistic regression model was statistically significant, χ2 = 72.89, p < 0.001. The model explained 15.0% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in unsatisfactory poor practice and correctly classified 61.4% of cases. Poor practice is associated with young age (OR = 2.41, 95% CI: 1.94–2.98) and low education (OR = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.03–1.37) and not working (OR = 4.95, 95% CI: 4.07–6.02).

4. DISCUSSION

This cross-sectional study aimed to assess the level of KAP among Egyptians toward COVID-19. For the COVID-19 battle, the population adherence to preventive measures is crucial; however, it is mainly affected by their KAP toward the disease [19]. In the present study, a good level of knowledge was observed among the studied participants, although 36.9% of the participants had a basic education level. This good knowledge could be attributed to the effective and intensive health awareness campaigns directed to all Egyptians as precautionary measures. A component of the integrated plan implemented by Egypt against COVID-19 pandemic was raising the public awareness [20]. This study was conducted weeks after the declaration of the pandemic, and participants reported receiving knowledge about COVID-19 through various channels, especially the social media and TV.

In accordance with the WHO standards, coordination between all Egyptian authorities started to launch continuous social awareness campaigns for citizens about COVID-19. These campaigns aimed to spread personal hygiene practices among the public and stressed on calling on people to stay home for everyone’s safety. The media also started awareness campaigns on the preventive measures against the virus through an informative awareness messages to reduce the number of new cases [21].

Added to these awareness efforts, advisory preventive guidance measures were issued to all health directorates for educating citizens about the pandemic [20]. Media plays an important protective role through raising the public awareness about protective measures and through the countering rumors. In this study, the source of information regarding COVID-19 for 80.8% of the participants was the social media. Of these campaigns issued against COVID-19 was “Protect yourself, protect your country”. All the campaigns depend mainly on promoting self-awareness, and highlight “commitment” as the ultimate weapon against the outbreak of the virus [22]. The observed satisfactory level of knowledge in the present study is consistent with that observed in a recent Chinese study done during a very early stage of the epidemic. The study observed that an overall correct response of 90% on the knowledge questionnaire. This good knowledge was explained by the high education level of the sample as 82.4% had an associate’s degree or higher, and the seriousness of the epidemic and receiving the pandemic news and reports through various channels [23].

Fortunately, this study showed a good level of knowledge when compared to a study done in 2009 to assess the KAP of Egyptian university students regarding H1N1, where only 39.8% of the participants answered ≥4 questions correctly [24]. But it was lower than the level of knowledge reported in a study done in 2010 to assess the rural community KAP regarding avian Influenza, where 75.7% of the respondents had a fair knowledge level [24]. Of the participants, 88.3% were pessimistic as they saw that the country instructions are not enough, only 36.5% saw that the disease will be contained soon, and 95.8% were afraid. This pessimistic attitude differs from that revealed from the previous Egyptian study done on avian flu, where 87.5% had a positive attitude toward prevention and control [25]. It differs from the Egyptian study done on H1N1, where 48.5% were afraid of death, and 47.3% thought that the disease may affect them or their families [24]. It also disagrees with results revealed from the Chinese study, where 90.8% thought that COVID-19 will be successfully controlled, and 97.1% were confident that China will win the battle against the COVID-19 [22].

This negative pessimistic attitude could be attributed to the frequent news received from all over the world about the seriousness and rapid speed of the disease and the increase in the number of patients and deaths in many countries, especially Italy, Spain and USA. In addition to the high mortality rate in Egypt that approximated 70% [26]. Another explanation of this negative attitude among the participants could be the known poor quality of most of Egyptian hospitals. This quality was documented in previous studies that pointed to the shortages in health care resources at different levels of care. These studies reported the poor infrastructure, the poor drug supply, the inadequacies in infection control measures and the poor health care providers’ performance because of the low motivation, insufficient training, poor communication and lack of protocols [27–29].

The Egypt’s government enforced a night-time curfew and banned all large community events and gatherings until further notice. The overall good practice was reported among 65.9%. This marked difference between the KAP of the participants was observed in the previous Egyptian study done on H1N1, where only 12.5% reduced their use of public transport, 25.1% reduced their shopping times, and 22.6% avoided crowded places [24]. This insufficient practice level is also in agreement with that present in the previous Egyptian study done on avian flu, where 58.1% of the participants had a fair practice level [25]. The sufficient hand hygiene practice among all participants is in consistent with that observed in the previous Egyptian study, where 87.5% washed their hands with soap and water frequently more than usual [24]. This adherence to hand washing practice could be explained by the health education massage given by all campaigns during the peak periods of infectious diseases transmission [30].

In the previously mentioned Chinese study [23], a highly better practice level was observed where 96.4% of the participants avoided crowded places, 98% wore masks on leaving home. This high compliance to preventive measures was attributed to the very strict prevention and control measures taken by the governments that prevented public gatherings, and the high knowledge level about the high infectivity of COVID-19 and its easy transmission through the unseen respiratory droplets. In this work, the high knowledge and low practice level reported among the middle-aged, working (especially in private working sector), and participants with insufficient income could be attributed to the engagement of a lot of Egyptians in working in the private sector [31].

In our study, workers in the private sector represented 61.3% of the sample, and unfortunately this sector did not commit to give workers a paid vacation as what happened in the government sector. This matter forced workers not to be committed to stay at home and risk their health to keep their work. According to the Egyptian Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics, there are shocking figures of the seasonal and intermittent workers. Those workers are representing 20% of the total number of workers in Egypt. Thus, they constitute the backbone of the economy. Perhaps that is why the government to pay 500 pounds as a financial grant for this employment after the curfew [31]. The lower practice level reported among male participants compared to females was also observed in the Chinese study, a matter that could be explained by the engagement of men in risky behaviors [22,32].

In the present study, participants with post-graduate education had the highest levels of KAP compared with other educational levels. This result agrees with previous studies [33,34]. This could be explained by the better access, understanding and comprehension of information by highly educated individuals [33,34]. This work showed that females had higher knowledge and practice levels and lower attitude compared to males. This could be explained by the higher perception of risk and more compliance with preventive behaviors among females [35].

Urban residents in this study showed a higher knowledge and attitude but a lower practice level compared to rural residents, a result that disagrees with previous KAP studies [35,36]. This work revealed that satisfactory KAP were found among 64.1%, 75.9% and 49.2% respectively. The observed lower practice level compared to knowledge and attitude levels is going on with studies that observed the poor translation from knowledge to practice [33,37].

The three pillars of KAP control the dynamic system of the human life. It was found that any increase in knowledge level subsequently will change the attitudes toward prevention of infectious diseases, and in turn change the related practices [38]. Logistic regression analysis found that low education was significant predictor for more unsatisfactory knowledge, and poor practice which concedes with other KAP studies [39]. Insufficient income was a predictor for more negative attitude which agrees with previous studies [36,40,41].

4.1. Strength and Limitations

This study took all groups representing the Egyptian society by inclusion of all levels of education, both genders, rural and urban areas residents, and an age that ranged from 12 to 82 years. This enables the generalization of this study results on all Egyptians. This issue enabled us to avoid the negative aspects of the previous Chinese study as its sample was over-representative of females, well-educated participants, and participants engaged in mental work, a matter that overestimated the knowledge, attitude and adherence to preventive practices. And made the Chinese study results generalized to high socioeconomic status Chinese sector especially women [35]. Limitation in this study was focused on the inability to direct in-depth health education to online participants about practice while we were able to distribute printed practice posters about hand hygiene to the other participants. The questionnaire also needed to contain more data about type of work (working hours, extent of dealing with public, availability of instructions about hand hygiene in work) and for students (if they take vacation or receive health education through their universities or schools).

5. CONCLUSION

This study showed that satisfactory knowledge, positive attitude and poor practice were found among the participants. A good knowledge and lower practice level were found among middle-aged, working participants, and participants with insufficient income. The demographic characters associated with KAP could be the cornerstone in directing policy-makers to target the health education campaigns to the suitable target groups.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

ZAK participated in getting the idea, study design, statistical analyses, drafting of the initial manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript. WAB, SKZ, MGH, SHA and EZ participated in data collection and reference search. DED participated in study design, drafting of the initial manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING

No financial support was provided.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This was obtained from the local ethical research committee and according to 1964 Helsinki Declaration.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Zeinab A. Kasemy AU - Wael A. Bahbah AU - Shimaa K. Zewain AU - Mohammed G. Haggag AU - Safa H. Alkalash AU - Enas Zahran AU - Dalia E. Desouky PY - 2020 DA - 2020/09/14 TI - Knowledge, Attitude and Practice toward COVID-19 among Egyptians JO - Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health SP - 378 EP - 385 VL - 10 IS - 4 SN - 2210-6014 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.200909.001 DO - 10.2991/jegh.k.200909.001 ID - Kasemy2020 ER -