Policy Disparities in Response to COVID-19 between China and South Korea

- DOI

- 10.2991/jegh.k.210322.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- COVID-19; non-pharmaceutical measures; diagnostic tests; quarantine or lockdown

- Abstract

Objectives: This study analyzed the effects of COVID-19 non-pharmaceutical measures between China and South Korea to share experiences with other countries in the struggle against SARS-CoV-2.

Methods: We used the generalized linear model to examine the associations between non-pharmaceutical measures adopted by China and South Korea and the number of confirmed cases. Policy disparities were also discussed between these two countries.

Results: The results show that the following factors influence the number of confirmed cases in China: lockdown of Wuhan city (LWC); establishment of a Leading Group by the Central Government; raising the public health emergency response to the highest level in all localities; classifying management of “four categories of personnel”; makeshift hospitals in operation (MHIO); pairing assistance (PA); launching massive community screening (LMCS). In South Korea, these following factors were the key influencing factors of the cumulative confirmed cases: raising the public alert level to orange (three out of four levels); raising the public alert to the highest level; launching drive-through screening centers (LDSC); screening all members of Shincheonji religious group; launching Community Treatment Center (LCTC); distributing public face masks nationwide and quarantining all travelers from overseas countries for 14 days.

Conclusion: Based on the analysis of the generalized linear model, we found that a series of non-pharmaceutical measures were associated with contain of the COVID-19 outbreak in China and South Korea. The following measures were crucial for both of them to fight against the COVID-19 epidemic: a strong national response system, expanding diagnostic tests, establishing makeshift hospitals, and quarantine or lockdown affected areas.

- Copyright

- © 2021 The Authors. Published by Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is spreading rapidly worldwide. Since WHO characterized the COVID-19 epidemic as a pandemic on March 11, 2020, COVID-19 has become a global concern. Compared with the coronaviruses causing Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, COVID-19 can be further transmitted via asymptomatically infected persons [1,2]. By October 14, the COVID-19 outbreak is affecting 214 countries and territories globally and two international conveyances, with the total confirmed cases were 38,432,182, the total death cases were 1,092,044 and more than 1 million confirmed cases in 106 countries. In an interview with the Global Times on October 11, Yang Gonghuan, Former Deputy Director of the China Center for Disease Control and Prevention told that the second wave of COVID-19 has already begun [3,4].

The first COVID-19 case was detected in Wuhan, China in early December 2019 which was the first country hit by the epidemic. Responding to the emerging infectious disease, the Chinese government acted quickly by carrying out strict non-pharmaceutical measures nationwide, which have proved to be effective in controlling the epidemic, saving people’s lives, and reducing the impact of the epidemic on the economy. China’s experience has proved that the national non-pharmaceutical measures suspended the development and contained the scale of the COVID-19 epidemic, avoiding hundreds of thousands of cases [5]. Also, South Korea was one of the countries hardest hit in the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak. The first COVID-19 case was identified on 20 January 2020 and superspreading events in the Daegu–Gyeongsang-buk provincial region caused a large number of infections and deaths in late February 2020. During the early phase of the outbreak as the number of COVID-19 cases increased, the Korean government raised the infectious disease alert to the highest level on February 23, 2020. Subsequently, the Korean government enhanced the screening and testing in the community (operation of drive-through screening centers and designation of private hospitals where COVID-19 screening and testing was available). South Korea mitigated the initial outbreak successfully without locking down any regions [6].

After the epidemic outbreak, China and South Korea adopted different non-pharmaceutical interventions to control the transmission of the COVID-19. This study summarized the non-pharmaceutical measures of the two countries and used the generalized linear model to analyze the association between the cumulative number of confirmed cases and non-pharmaceutical measures. We hope these findings will help other countries combat the COVID-19 outbreak.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Data Collection

Data on COVID-19 cases in China were obtained from the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, which provides daily updates with individual case data on a dedicated web page and the COVID-19 cases of South Korea were collected in the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center web page. This data includes cumulative and daily confirmed cases. Data were collected from January 20, 2020 through May 31, 2020.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Generalized linear model was used to explore the association between the non-pharmaceutical measures and the cumulative number of confirmed cases in China and South Korea. In this model, the cumulative number of confirmed cases of China and South Korea was as a dependent variable whereas the non-pharmaceutical measures were as independent variables, respectively.

3. THE COVID-19 OUTBREAK AND NATIONAL RESPONSE

3.1. Response Strategies in China

China’s epidemic prevention and control have been divided into three stages:

- (1)

At the initial stage of the epidemic before the new COVID-19 case outbreak, the Chinese authorities performed large-scale elimination and epidemiological investigations nationwide and established a strong epidemic command system, which ensured the decision-making efficiency and synchronicity of policies in all regions.

- (2)

During the spread of COVID-19, the core prevention and control policies can be summarized as “four early’s” and classify management of “four categories of personnel”. The “four early’s” required that the COVID-19 cases should be early detection, early reporting, early isolation, and early treatment. The “four categories of personnel” were confirmed cases, suspected cases, febrile patients who might be carriers, and close contacts. All confirmed cases were transferred to hospitals for centralized treatment, suspected cases, febrile patients who might be carriers, and close contacts were sent to designated venues for isolation and medical observation. These policies can effectively isolate the source of infection and cut off the route of transmission while preventing cross-infection. Besides, the Chinese government established Huoshenshan Hospital, Leishenshan Hospital, and Fangcang shelter hospitals in Wuhan to contain the spread of the COVID-19 outbreak nationwide [7].

- (3)

With the newly confirmed cases in Hubei being zero for several consecutive days, the epidemic has initially entered a stable stage [8]. On April 7, 2020, Wuhan was lifted of lockdown and the Chinese government relaxed a series of strict public health measures, which means that China has entered the phase of ongoing epidemic prevention and control. We summarized the major non-pharmaceutical measures in Table 1.

| S. No. | Date | Policy | Key elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jan 23 | Lockdown of Wuhan city (LWC) | Wuhan government announced that Wuhan city began a lockdown on January 23, 2020 and then all villages in Hubei province enclosed. On April 8, Wuhan lifted lockdown. |

| 2 | Jan 25 | Establishment of a Leading Group by the Central Government | On January 25, 2020, the Central Government established a Leading Group on coping with the COVID-19 and decided to send guidance groups to Hubei province and other seriously affected areas to enhance the front-line prevention and control work. |

| 3 | Jan 29 | Raising the public health emergency response to the highest level in all localities | With the highest-level public health emergency response launched in all provinces, China has entered a state of emergency epidemic prevention. |

| 4 | Feb 2 | Classifying management of “four categories of personnel” | Wuhan put four categories of people (confirmed cases, suspected cases, febrile patients who might be carriers, and close contacts) under classified management in designated facilities and conducted mass screening. |

| 5 | Feb 5 | Makeshift hospitals in operation (MHIO) | Two emergency specialty field hospitals, Huoshenshan Hospital and Leishenshan Hospital were launched for severe or critical condition patients. 16 Fangcang shelter hospitals were opened for patients with mild symptoms and treated more than 12,000 patients in Wuhan. |

| 6 | Feb 13 | Pairing assistance (PA) | The massive mobilization of medical staff, which aims to assist 16 cities besides Wuhan, was started on February 11, 2020, while the “pairing assistance” medical personnel got to work in pairing cities from February 13, 2020 (the 22nd day after the lockdown of Wuhan). |

| 7 | Feb 19 | Launching massive community screening (LMCS) | During the outbreak, a number of cities closed off residential communities and a Joint Defence Team (which consists of general practitioners, the local neighborhood committees and community police) was established to screen patients. |

The major epidemic prevention and control policies in China

3.2. Response Strategies in South Korea

In the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak, imported cases from China and their related cases were detected, the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention actively conducted contact tracing, isolated the contacts, and diagnosed and quarantined the COVID-19 cases as soon as possible. In February, when the city of Daegu and Gyeongsangbuk-do was hit by an explosive outbreak, mass screening was performed to identify mild or no symptoms patients. To screen for COVID-19 patients safely and efficiently, South Korea has designed and implemented drive-through screening centers [9]. The public has been encouraged to remain social distancing and prohibit unnecessary going out to contain the spread of the COVID-19 outbreak. These measures mitigated the initial outbreak successfully. So on April 19, 2020, the Korean government softened social distancing measures and began to enter the phase of normal life and epidemic prevention and control. The major approaches were summarized in Table 2.

| S. No. | Date | Policy | Key elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jan 27 | Raising the public alert level to orange (three out of four levels) | The Korean government raised the alert level to orange when the first imported case of COVID-19 was confirmed in South Korea on January 20, 2020. |

| 2 | Feb 23 | Raising the public alert to the highest level | As the number of confirmed cases was rapidly increasing, the Korean government raised the alert level from orange to red on February 23, 2020. The Ministry of Education ordered the closure of all schools and delayed the new school year opening by 1 week. |

| 3 | Feb 23 | Launching drive-through screening centers (LDSC) | For safe and efficient screening of the COVID-19 patients, drive-through screening centers have been designed and implemented in South Korea. The steps of the drive-through screening centers include registration, examination, specimen collection and instructions. |

| 4 | Feb 24 | Screening all members of Shincheonji religious group | A large number of COVID-19 cases and deaths were related to the Shincheonji religious group activities. The Korean government screened all members to control the transmission. |

| 5 | Feb 27 | Launching Community Treatment Center (CTC) | To allocate medical resources efficiently, a novel institution with the purpose of treating patients with cohort isolation out of the hospital, namely the CTC, was designed and implemented in South Korea. |

| 6 | March 8 | Distributing public face masks in nationwide | The Korean government announced a ban on the export of masks from March 6 and a restriction on the purchase of masks. |

| 7 | March 21 | Implementing strict social distancing measures | Along with the high public alert, the implementation of strict social distancing measures on March 21, 2020. Softening social distancing measures on April 19. |

| 8 | April 1 | Quarantining all travelers from overseas countries for 14 days | In light of the increasing number of confirmed cases especially among inbound travelers, from 00:00 April 1 all travelers entering Korea are subject to a 14-day quarantine from the day after arrival. |

The major prevention and control policies in South Korea

4. RESULTS

4.1. Epidemiological Timeline of COVID-19 in China and South Korea

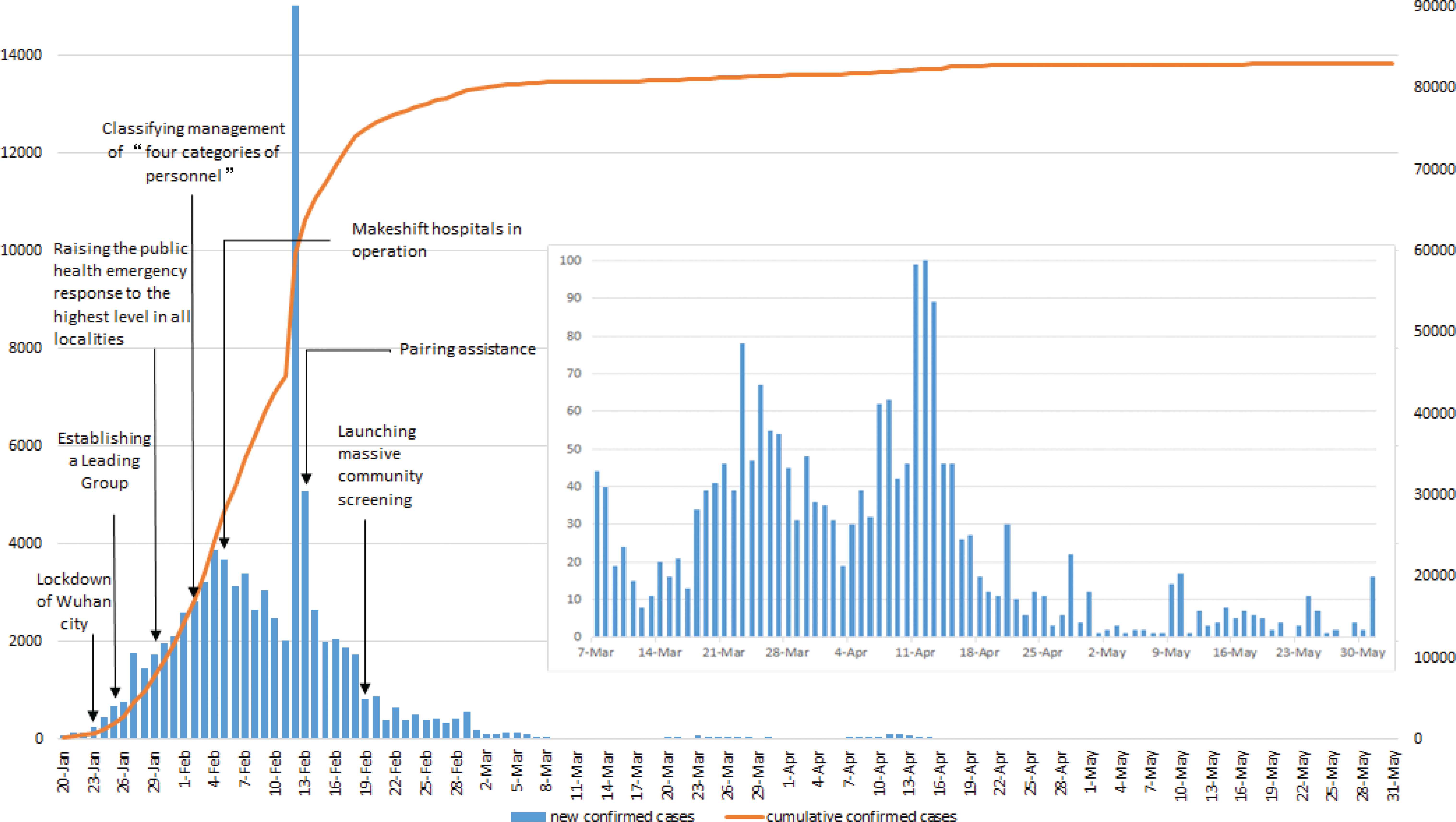

Figure 1 shows the epidemiological timeline of COVID-19 and the implementation of non-pharmaceutical measures between January 20 and May 31, 2020, in China. Figure 1 also finds that before March 5, the number of COVID-19 cases increased rapidly. During this phase, the Chinese government adopted a series of non-pharmaceutical inventions to contain the COVID-19 epidemic and reduced the number of COVID-19 patients. Since March 7, the daily new cases have remained below 100.

COVID-19 epidemic curve and the timeline for implementation of non-pharmaceutical measures in China. Note: The inset box shows daily new cases since March 7, 2020.

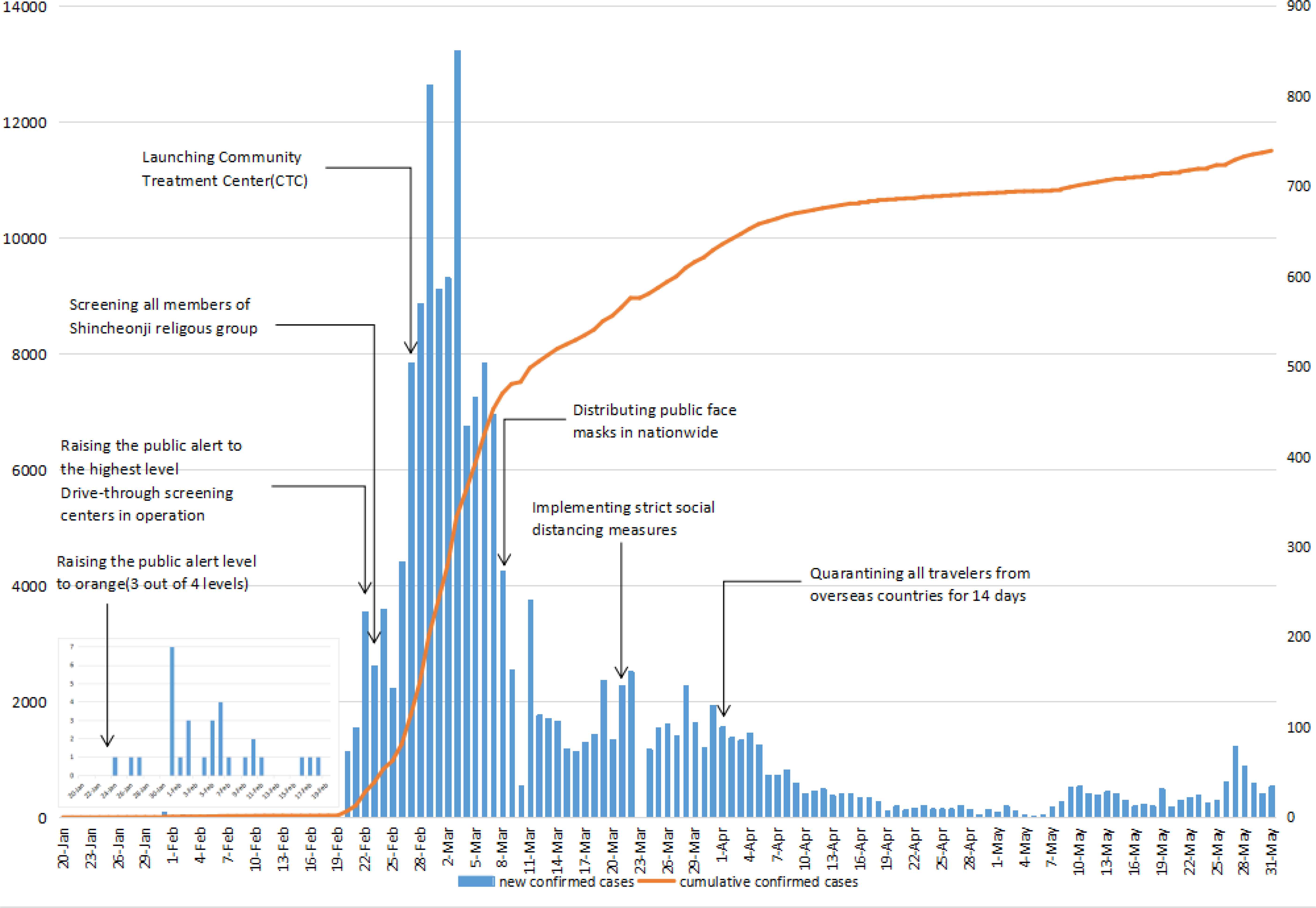

Figure 2 shows the epidemiological timeline of COVID-19 and the implementation of non-pharmaceutical measures between January 20 and May 31, 2020, in South Korea. Figure 2 also finds that daily new confirmed cases were a single-digit increase between January 20 and February 19, 2020. The total number of confirmed cases has increased rapidly since February 20, 2020, which was caused by a super-spread incident within a religious group called Shincheonji in Daegu city. After the COVID-19 outbreak, the Korean government implemented some non-pharmaceutical measures to control the explosive outbreak. After April 2, the number of newly confirmed cases, about 100 cases is occurring steadily every day.

COVID-19 epidemic curve and the timeline for implementation of non-pharmaceutical measures in South Korea. Note: The inset box shows daily new cases between January 20 and February 19, 2020.

4.2. Association between the Major Non-pharmaceutical Measures and the Cumulative Number of Confirmed COVID-19 Cases

In the generalized linear model, we used the total number of confirmed cases in China as dependent variable Y, and the seven non-pharmaceutical measures in Table 1 as independent variable X1–X7 respectively. The result of Table 3 suggested that the implementation of the seven non-pharmaceutical measures had an impact on the cumulative number of confirmed cases in China. For South Korea, we used the cumulative number of confirmed cases as dependent variable Y, and the eight non-pharmaceutical measures of Table 2 as independent variable X1–X8 respectively. The result of Table 4 indicated that these seven following measures of South Korea had an impact on the cumulative number of confirmed cases: Raising the public alert level to orange (three out of four levels); raising the public alert to the highest level; launching drive-through screening centers (LDSC); screening all members of Shincheonji religious group; Launching Community Treatment Center (LCTC); distributing public face masks in nationwide; quarantining all travelers from overseas countries for 14 days.

| Parameter | B | 95% CI | Wald Chi-square | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 11.790 | 11.787, 11.793 | 54179360.813 | 0 |

| Lockdown of Wuhan city | 0.287 | 0.284, 0.289 | 54053.671 | 0 |

| The Central Government established a Leading Group | −3.290 | −3.328, −3.252 | 28849.704 | 0 |

| Raising the public health emergency response to the highest level in all localities | 0.018 | 0.016, 0.020 | 299.446 | 0 |

| Classified management of “four categories of personnel” | −0.481 | −0.485, −0.478 | 74801.048 | 0 |

| Started the operation of makeshift hospitals | −0.073 | −0.075, −0.071 | 5285.379 | 0 |

| Pairing assistance | −1.027 | −1.031, −1.023 | 286703.597 | 0 |

| Launched massive community screening | −0.243 | −0.245, −0.241 | 37619.823 | 0 |

CI, confidence interval.

Associations between the major transmission control measures and the cumulative number of COVID-19 cases reported in China

| Parameter | B | 95% CI | Wald Chi-square | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 12.516 | 11.860, 13.171 | 1399.470 | 0 |

| Raising the public alert level to orange (three out of four levels) | −3.230 | −3.886, −2.575 | 93.233 | 0 |

| Raising the public alert to the highest level | −5.812 | −6.471, −5.154 | 299.585 | 0 |

| Launching drive-through screening centers | −0.592 | −0.682, −0.503 | 169.036 | 0 |

| Screening all members of Shincheonji religious group | 0.061 | 0.043, 0.080 | 42.378 | 0 |

| Launching Community Treatment Center | −1.499 | −1.536, −1.463 | 6471.397 | 0 |

| Distributing public face masks in nationwide | −0.629 | −0.639, −0.618 | 14328.106 | 0 |

| Implementing strict social distancing measures | 0.001 | −0.004, −0.005 | 0.049 | 0.824 |

| Quarantining all travelers from overseas countries for 14 days | −0.226 | −0.231, −0.222 | 7933.630 | 0 |

CI, confidence interval.

Associations between the major transmission control measures and the cumulative number of COVID-19 cases reported in South Korea

5. DISCUSSION

This study found that China and South Korea successfully controlled the COVID-19 outbreak with major non-pharmaceutical measures implementation. Figures 1 and 2 show that the outbreak time of COVID-19 was different between China and South Korea. In China, the total number of cases increased rapidly before March due to Wuhan city which was first hit by the outbreak explosive. The Chinese government had adopted public health interventions to control the epidemic, but containing the transmission of the outbreak was a long-term process due to the characteristic of COVID-19 is highly contagious and has a long incubation period. In South Korea, when the first COVID-19 case was identified, the Korean government quickly raised the public alert level to orange (three out of four levels), so in the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak, the cases were a single-digit increase. But since February 20, 2020, the number of cases increased rapidly because of the superspreading with a religious group. Subsequently, the Korean government implemented public health measures to suppress this explosive outbreak spread.

The experience of China and South Korea proved that after the implementation of multifaceted non-pharmaceutical measures (including but not limited to strengthening urban and intercity traffic restriction, social distancing measures, home isolation, and centralized quarantine, and improved medical resources), the COVID-19 cases were decreased and the outbreak was better under control [10]. The generalized linear model results of Tables 3 and 4 suggest that the implementation of non-pharmaceutical measures in China and South Korea had disparities but had a lot in common.

5.1. Disparity of Non-pharmaceutical Measures between China and South Korea

This study found that the significant disparity of non-pharmaceutical measures between China and South Korea was whether locked down infected areas on a large scale. China implemented more rigorous and radical lockdown measures. When the COVID-19 epidemic outbreak, the Chinese government Lockdown Wuhan City (LWC). Subsequently, lockdown infectious areas were expanded to other cities in Hubei province or other provinces in China. People were required to stay at home to block the transmission of COVID-19 epidemic thoroughly. But South Korea adopted more moderate precautions based on maintaining a relatively normal social life and did not lockdown somewhere to control the COVID-19 epidemic.

This study also found that South Korea chose to focus first on the “point” (targeting the outbreak area and tracking the trajectory of the infected in detail), while China prioritized the “surface” (complete closure of the city and decreasing social activities to quarantine at home as much as possible). Thus, in response to the COVID-19 outbreak, South Korea did not quarantine or lockdown affected areas on a large scale, but in Daegu city and North Gyeongsang Province, the maximum lockdown measures have been taken in these two areas to contain the outbreak [11] such as distributing public face masks nationwide and quarantining all travelers from overseas countries for 14 days.

While China, on the contrary, implemented a strict quarantine strategy - LWC (suspending all traffic in and out of the city from January 23 to April 7, 2020, in Wuhan). Moreover, studies proved that it was China’s strict non-pharmaceutical measures that avoided hundreds of thousands of cases by February 2020 (day 50) [5]. Of course, the difference in the two priority methods may be due to different national conditions.

5.2. Commonalities of Non-pharmaceutical Measures between China and Korea

5.2.1. Strong national response system

This study found that after the COVID-19 outbreak in China, all localities raised the public health emergency response to the highest level from January 23 to 29, 2020, and China has entered a state of emergency epidemic prevention. On January 25, the Central Government established a Leading Group on coping with the COVID-19 and decided to send guidance groups to the epicenter of the outbreak - Wuhan city. Similarly, when the first case of COVID-19 was detected in South Korea, the Korean government adjusted the national infectious disease crisis level from “Alert” to “Warning”, and the COVID-19 Emergency Headquarters was in operation on January 27. On February 23, the government raised the national infectious disease crisis level from “Warning” to “Serious” and declared Daegu and Gyeongsangbuk-do as the infectious disease special management zone [12]. As seen in Figures 1 and 2, with the national public health emergency response of the COVID-19 epidemic, the government of China and South Korea adopted a series of non-pharmaceutical measures to flat the rapidly expanding epidemic curve and achieved significant results.

5.2.2. Expanding diagnostic tests

The early detection of potential cases was crucial in controlling COVID-19 outbreaks. In China, with the improvement of medical resources (the increase of designated hospitals and wards, the use of personal protective equipment, the improvement of detection capacity and the acceleration of reporting, and medical treatment in time), the Chinese government classified management of “four categories of personnel” on February 2, 2020 [10]. On February 19, with support from thousands of community workers, the government launched massive community screening (house-to-house and individual-to-individual symptom screening for all residents). Screening for suspected cases in the community has further reduced the transmission of COVID-19.

Similarly, to respond to the rapid increase of COVID-19 cases in late February, drive-through testing centers were in operation on February 23 in South Korea. Drive-through testing centers were one-third shorter than the conventional screening process, and only took about 10 min per one test. As of April 10, 73 drive-through test centers could be able to carry out diagnostic tests in South Korea [12,13]. On February 24, the Korean government screened all members of the Shincheonji religious group to contain the transmission.

5.2.3. Establishing makeshift hospitals

This study found that when the number of COVID-19 cases increased rapidly in Wuhan city, Wuhan built two makeshift hospitals: Leishenshan Hospital and Huoshenshan Hospital, replicating Beijing’s Xiaotangshan Hospital, which treated SARS patients in 2003, to alleviate the lack of medical resources and further increase the admission of patients [14]. Between February 5 and March 10, Wuhan had opened a total of 16 square cabin hospitals through the reconstruction of the exhibition center and gymnasium, which can receive and cure more patients and suspected cases, such as close contacts of confirmed cases. By March 10, the 16 Fangcang shelter hospitals were all closed due to a decrease in the number of patients. These hospitals received more than 12,000 patients of COVID-19 in Wuhan, accounting for nearly 25% of the city’s patients, according to the National Health Commission [15]. Also, China has proposed a solution by taking a “pairing assistance” measure nationwide, which was that mobilizing 29 provinces to relieve pressure on cities in Hubei province to ensure that there were adequate numbers of medical personnel [16].

This study also found that since February 19, 2020, the rapidly increasing number of COVID-19 cases in South Korea has led to overcrowding of limited hospital resources and forced confirmed patients to stay at home. To allocate medical resources effectively, South Korea built the CTC, which was a novel institution for treating patients with cohort isolation out of the hospital. The CTC aims to monitor and isolate patients with mild symptoms during an outbreak of emerging infectious disease. As of March 25, there were 17 CTCs nationwide serving patients with mild conditions, and as of March 26, the 17 CTCs had treated a total of 3292 patients, accounting for 35.6% of the 9241 confirmed cases in South Korea [17,18].

6. CONCLUSION

Our study found that a series of non-pharmaceutical measures were associated with contain of the COVID-19 outbreak in China and South Korea. The following measures were crucial for both of them to fight against the COVID-19: a strong national response system, expanding diagnostic tests, establishing makeshift hospitals, and quarantine or lockdown affected areas.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

HQC and GS conceived the paper. HQC, YYZ and XHW collected the data. HQC drafted the manuscript. LYS, YYZ and XHW revised the manuscript. GS contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

FUNDING

This work was supported by

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial supports by the National Social Science Fund of China (No. 16BGL184), thank all study participants who have been involved and contributed to the procedure of data collection.

ABBREVIATIONS

- LWC,

Lockdown Wuhan city;

- MHIO,

Makeshift hospitals in operation;

- PA,

Pairing assistance;

- LMCS,

Launching massive community screening;

- LDSC,

Launching drive-through screening centers;

- LCTC,

Launching community treatment center;

- CTC,

Community Treatment Centers;

- COVID-19,

Coronavirus disease 2019.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT COMPLIANCE STATEMENT

Not applicable.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Haiqian Chen AU - Leiyu Shi AU - Yuyao Zhang AU - Xiaohan Wang AU - Gang Sun PY - 2021 DA - 2021/03/29 TI - Policy Disparities in Response to COVID-19 between China and South Korea JO - Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health SP - 246 EP - 252 VL - 11 IS - 2 SN - 2210-6014 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.210322.001 DO - 10.2991/jegh.k.210322.001 ID - Chen2021 ER -