Community Foodborne of Salmonella Weltevreden Outbreak at Northern Governorate, Sultanate of Oman

, Seif S. Al-Abri2,

, Seif S. Al-Abri2,  , V. Vidyanand1,

, V. Vidyanand1,  , Idris Al-Abaidani2,

, Idris Al-Abaidani2,  , Amal S. Al-Balushi1,

, Amal S. Al-Balushi1,  , Shyam Bawikar2,

, Shyam Bawikar2,  , Emadeldin El Amir1, Saleh Al-Azri3,

, Emadeldin El Amir1, Saleh Al-Azri3,  , Rajesh Kumar3,

, Rajesh Kumar3,  , Azza Al-Rashdi3,

, Azza Al-Rashdi3,  , Amina K. Al-Jardani3

, Amina K. Al-Jardani3- DOI

- 10.2991/jegh.k.210404.001How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Salmonella Weltevreden; rapid response team; outbreak investigation; serotyping

- Abstract

Objectives: To investigate the course of a community gastroenteritis outbreak by Salmonella and implement interventional activities and roles to prevent occurring such an outbreak in the future.

Methods: From August 27 to 2 September 2015, 101 individuals were reported among a local community. All affected individuals had a history of food consumption at a local restaurant. A rapid response team conducted active surveillance and interview with the affected individuals and workers of the restaurant. Food items and stools from food handlers and affected individuals were cultured and sent for genotyping. An environmental audit of the restaurant had been conducted.

Results: The total majority of the affected individuals were male and more than 70% belonged to the young age group from 15 to 45 years. Out of the total, 97% had diarrhea, 70% fever, 56% abdominal cramps and 49% vomiting. All those affected were managed symptomatically except for 14 cases admitted for intravenous rehydration. Breakdown of food safety and basic personal hygiene were detected in the environment of the restaurant and among the workers. There are 39 out of 49 stool cultures of cases, six out of 18 food handlers, and five food samples were positive for Salmonella spp. The identical DNA fingerprinting pattern among S. Weltevreden strains originating from human cases and food was detected.

Conclusion: This is the first reported community foodborne of S. Weltevreden outbreak in Oman. The importance of food safety and rigors environmental safety is emphasized. Basic personal hygiene and training of food handlers in restaurants are recommended with public health measurements.

- Copyright

- © 2021 The Authors. Published by Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

Non-typhoidal Salmonella is one of the most common bacterial diarrheal acute gastroenteritis. Globally, it is classified as an important public health issue [1]. The most common transmission is through raw and uncooked meat, poultry eggs, dairy food items, and contaminated water [1]. Reported outbreaks from domestic animals are identified [2]. Contaminated drinking water is also a common source [3]. The most common agents associated with non-typhoidal salmonellosis are Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis, Typhimurium [3–5]. An outbreak of S. Weltevreden has been reported most frequently from South-East Asia [1,6–8]. It has been identified among food-borne outbreaks [4].

We report an outbreak among the community at the Northern part of the Sultanate of Oman in August 2015. Individuals who presented to the accident and emergency department at a local hospital were complaining of abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever. All individuals gave similar history of taking food from a local restaurant the previous night. The source of the outbreak was suspected to be from the assigned restaurant including food handlers, food items, and water. Hence, an investigation of the outbreak was performed to determine the etiological factor and identify associated risk factors to take necessary actions to prevent similar outbreaks in the future.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Background

On August 27 2015, at midnight, the first affected individual suffering from symptoms consistent with gastroenteritis was admitted to the accident and emergency department at a local hospital. The unusual numbers of individuals with same complaint attending the local hospital suggested a point-source of the outbreak. There were 101 notified affected individuals for 3 days. An affected individual was defined as an individual presenting with acute onset of diarrhea or vomiting with or without fever with other symptoms such as abdominal pain, headache, and lethargy and had a history of food consumption from the local restaurant. We received the information of suspected outbreak through the medical officer-in-charge of the hospital on 31 August 2015. Other related sectors were notified about the suspected outbreak like local municipality to participate and control of the outbreak. Immediately, the restaurant was closed as it was suspected the source of the outbreak.

2.2. Epidemiological Investigation

The regional Rapid Response Team (RRT) was activated immediately, including the public health specialist, regional epidemiologist, infection control nurse, and sanitary supervisor. The aim of this study was to investigate the source of the outbreak, implement activities to control the outbreak, and recommend action plans to prevent further similar conditions. RRT visited the local hospital and all staffs were educated about the case definition and the management process. National case notifications format and computer records were reviewed to know the details of time with types of food consumed and time of onset signs and symptoms after exposure. More information and details were gathered retrospectively by telephonic interviews of the cases after a week’s time. Complete information with relevant details was collected from the notified cases and a line list was prepared and data analysis was done. All mild cases were managed at the hospital and the severe cases were referred to the regional secondary care hospitals. Interviews were conducted with health care workers, patients, and food handlers.

2.3. Environmental Investigations

The RRT and the local municipality authority visited the restaurant to perform a general inspection, interview the workers and collect samples from raw food, food handlers, and water. The visit was immediate, and the team used the Investigation of Foodborne Disease Outbreak Format, which is designed by the Department of Communicable Disease, Ministry of Health, Sultanate of Oman, as a tool for collecting required information. It contains demographic, risk factors, details of food, the onset of signs and symptoms, investigations, treatment, and outcome for each case. There were 101 forms fully completed. These forms were distributed to all health care facilities in the Governorate to fill for each patient related to this outbreak.

2.4. Laboratory Investigations

Stools samples from 47 suspected cases were collected at the local hospital laboratory for culture and sensitivity. Samples of remaining implicated food, uncooked food, and raw food material were also collected for laboratory analysis and bacterial culture. Swabs from cutting knife-1, cutting board, knife-2, and place of dough making were also collected for bacterial culture. The stool samples were inoculated on various culture plates including - MacConkey Agar (MC), Thiosulfate-Citrate-Bile Salts-Sucrose (TCBS), and Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate (XLD), Campy agar, Yersinia agar, Sorbitol MacConkey Agar and incubated for 24 h at 36 ± 1°C. Subsequently, the stool samples were also inoculated in selenite broth and alkaline peptone water for selective enrichment and incubated for 24 h at 36 ± 1°C. After overnight incubation at 36 ± 1°C, all the plates were examined for colony morphology and utilization of lactose/sorbitol. Strains with growth on XLD were presumptively identified as Salmonella. Identification confirmation was done by API20E kits (BioMérieux Inc., SA, France). Salmonella strains were subjected to complete serotyping using polyvalent grouping antisera & monovalent somatic “O” (Difco, BD Diagnostics, NJ, USA) and flagellar “H” antisera (Denka Seiken Co., Ltd., Niigata, Japan).

A total of five food samples were received at the food and water section, public health laboratories, Muscat for microbial analysis. About 25 g of each food sample was added in 225 mL of buffered peptone water and homogenized. Food homogenate was inoculated on - MacConkey Agar (MC), XLD agar, TCBS agar, Campy agar, Yersinia agar, Sorbitol MacConkey Agar, Blood Agar, Listeria agar, Bacillus agar and incubated for 24 h at 36 ± 1°C. Simultaneously, food homogenate was inoculated in alkaline peptone water and selenite broth for selective enrichment and incubated for 24 h at 36 ± 1°C. After adequate incubation at 36 ± 1°C, all the plates were examined for colony morphology and utilization of lactose/sorbitol. Strains with growth on XLD were presumptively identified as Salmonella. Identification confirmation was done by API20E kits (Biomerieux Inc.). Salmonella strains were subjected to complete serotyping using polyvalent grouping antisera & monovalent somatic “O” (Difco, BD Diagnostics) and flagellar “H” antisera (Denka Seiken Co., Ltd.).

Randomly selected isolates of Salmonella spp. from the patients and food samples were subjected for complete serotyping based on somatic O and phase 1 and 2 of the flagellar H antigens by latex agglutination tests with commercial antisera in the laboratory as specified in the Kauffmann–White protocol for Salmonella spp. serotyping.

Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis was performed on randomly selected Salmonella spp. isolates using Pulse Net protocol PNL05 (The updated protocol is available at https://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/pathogens/pfge.html.). Briefly, freshly grown colonies of bacteria (18–24 h growth) were suspended in cell suspension buffer to achieve optical density of 1 (range 0.8–1) at 260 nm wavelength on a spectrophotometer. Proteinase K, 10 μl/sample (20 mg/ml stock) was added to cell suspension and plugs were prepared by mixing 200 μl cell suspension with 200 μl molten sachem gold agarose. Plugs (4–5/sample) were added in a 5-ml of cell lysis buffer in 50 ml Falcon tube and cell lysis was performed at 56°C in water bath for 1.5 h with constant vigorous shaking. After cell lysis, plugs were washed two times with 10–15 ml of sterile ultrapure distilled water; followed by four washings with sterile TE buffer. A small slice of plug for each isolate was cut and digested in 200 μl restriction solution comprising 5 μl (10 Units/5 μl) XbaI enzyme, 1 μl BSA (20 mg/ml), 20 μl restriction buffer and 174 μl sterile distilled water. The plug slices were incubated at 37°C for 1.5 h to complete the restriction. Electrophoresis using restricted plug slices was performed on CHEF DRIII system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Following run parameters were used: Initial switch time 2.2 seconds, final switch time 63.8 s, voltage 6 V, angel 120°, and runtime of 18 h. Salmonella Braenderup H9812 strain was used as control and molecular size marker. After electrophoresis was over, the gel was stained for 20 min at room temperature in 400 ml ultrapure water by adding 40 μl of ethidium bromide (10 mg/ml). The gel was de-stained three times in 500 ml ultrapure water (15 min/cycle). Image of the de-stained gel was taken on Gel Dock system (Bio-Rad) and saved in Pulse Net Tiff format for further analysis. Tiff image was analyzed on the BioNumerics software version 5.1 (Applied Maths, Belgium).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Epidemiological Investigation

From the line listing, 101 persons were identified with gastroenteritis symptoms at the local hospital Accident and Emergency Department (A&E). Of the total, 64.4% (65 cases) are male and 35.6% (36 cases) are females. The cases were distributed over the village with no clustering in a specific area. All age groups were affected, however, more than 70% belonged to the young age group from 15 to 45 years (Table 1).

| Age group (years) | Number of exposed | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0–14 | 23 | 23.2 |

| 15–29 | 49 | 47.5 |

| 30–44 | 24 | 24.2 |

| 45 and above | 5 | 5.1 |

Distribution of cases by age group and food poisoning outbreak (August 2015)

The most common symptoms were diarrhea (97% cases), fever (70%), abdominal cramps (56%), and vomiting (49%) (Figure 1). However, there was no history of melena. Only 14 cases were admitted to the local hospital for observation with a maximum duration of 3 days. There were no gastroenteritis complications or deaths due to Salmonella infection notified. All those affected recovered uneventfully.

Frequency of signs and symptoms in percentage: S. Weltevreden outbreak on August 15, Oman (n = 101).

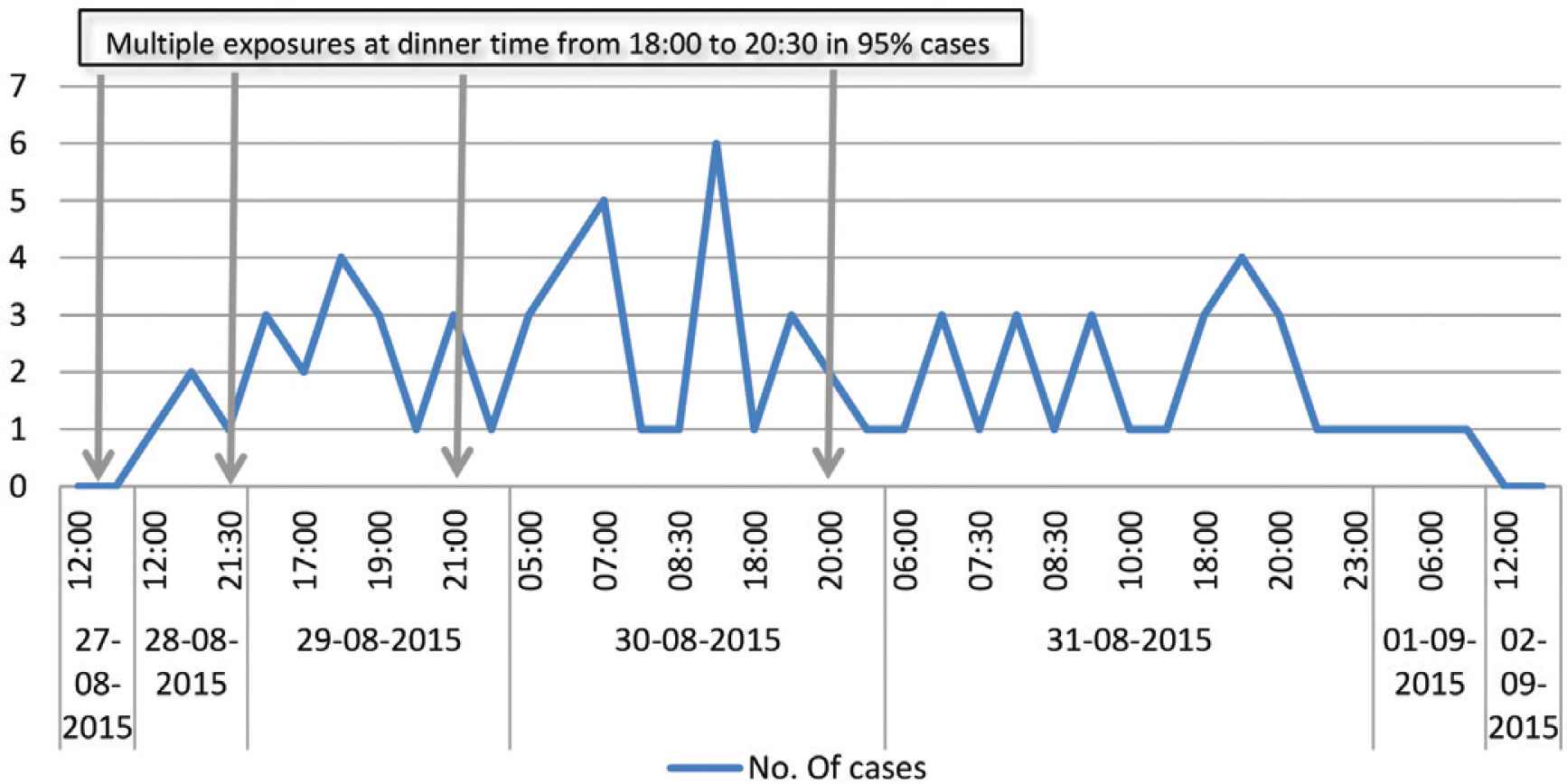

The outbreak curve (Figure 2) summarizes data from the 101 cases line listing from the local hospital A&E and suggests the local restaurant is the source of the outbreak. The first symptomatic case was presented on midnight 27 August 2015 and the last case was on 30 August 2015. The onset time for symptoms of most cases was on 30 August 2015. From the outbreak curve, showing cases decline and no cases reported on first September 2015 after restaurant closure early morning on 31st August 2015, we can consider the restaurant is the source of the outbreak. The minimum Incubation Period (IP) was 9 h and maximum was 29 h 30 min. The median IP was 17 h (Figure 2).

Epidemic curve: day and time of distribution of onset of cases from 28 August to 1 September 2015 and four exposure time periods: S. Weltevreden outbreak on August 15, Oman.

The details about the type of food items consumed could be recorded in 60 cases. In 38 cases there was a history of consumption of hummus, 32 chicken, 14 vegetable salads, and 10 motabbal. The proportional food-specific attack rates were for hummus 63%, chicken 53%, vegetable salad 24%, and motabbal with rice 16% (Table 2).

| Food items | Cases with h/o consumption | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hummus | 38 | 63.3 |

| Chicken | 23 | 38.3 |

| Veg. salad | 17 | 28.3 |

| Mixed grill | 7 | 11.6 |

| Motabbal | 10 | 16.7 |

| Meat | 4 | 6.7 |

| Bread | 1 | 1.7 |

| Rice | 10 | 16.7 |

Proportional food attack rates (n = 60)

3.2. Environmental Investigation

The sanitary conditions of the restaurant were poor and not adequate for the preparation of safe food. The main source used to prepare food was tap water. All the waste was dumped in the dustbin behind the restaurant in an open space. No quarantine facility was available for spoiled or expired food items. Every day, before closing the restaurant the remaining foods were kept in refrigerators to be served on the next day. Refrigerators and deep fridge were in good working condition. All the raw materials used to prepare food was stored in a small room, attached to kitchen along with two deep freezers without air conditioner. All the raw materials inspected was within expiry date as per the labels. There was no evidence of rodents or cockroach infestation. However, there were no visible evidence of regular measure undertaken neither records of pest controls.

There were 18 food handlers working in the restaurant. The general personal hygiene was extremely poor. All of them used to take over each other’s work as per the need and demand. No hand gloves or caps were used during the food preparation. Food handler’s rest area was untidy, and toilets were dirty. All food handlers eat food prepared within the restaurant. However, none of them complained of any signs and symptoms of gastroenteritis. All the food handlers were examined clinically and were normal. Stool samples, throat swabs, nail bed scrapings were collected under supervision from all 18 food handlers for culture and sensitivity.

Interview with the cooker who was responsible for preparing the hummus revealed that the raw material (boiled chickpeas were grounded and made in balls of approximately 1 kg weight) was prepared in bulk and kept in the deep fridge. To prepare hummus for next day the required approximate amount was taken out from the deep fridge and kept outside at room temperature (40°C) overnight to defrost. Next day morning at 10 am approximately the other material like tahini (readymade product of grounded sesame seeds) was mixed with defrosted raw ball to prepare the hummus. This was done in the special mixture cum grinder dedicated to hummus preparation only. This prepared hummus used to be kept outside at room temperature and used for the entire day. The remaining hummus at the end of the day was discarded in the night and fresh humus would be prepared for next day. The mixture cum grinder was not thoroughly cleaned and dried before grinding the next day’s preparation as observed.

3.3. Laboratory Results

Stools samples from 47 suspected cases were collected at the local hospital laboratory for culture and sensitivity. Also, samples of remaining implicated food, uncooked food, and raw food material were collected for laboratory analysis and bacterial culture. Swabs from cutting knife-1, cutting board, knife-2, and place of dough making were collected for bacterial culture. Moreover, stools, throat swabs, and nail swab had been collected from food handlers.

There were 39 out of 47 stool cultures of cases, six out of 18 food handlers and five food samples were positive for Salmonella spp. Cut pieces of raw meat were unsatisfactory for food as per bacteriological standards. As per preliminary laboratory examination of remnant food samples shown that chicken and hummus smelt bad and fried chicken was undercooked. Escherichia coli and coliform cultured in tested food and kitchen tools swabs. One of the food handlers’ hand and nail swab was also positive for E. coli and coliform. However, water used for food preparation and drinking was negative for any harmful bacterial growth (Table 3).

| No | Sample | Number | Date collected | Test | Laboratory | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stools of the cases | 47 | 28–31 August 2015 | Culture/sensitivity | Saham Hospital | 39 positives for Salmonella |

| 2 | Stools of food handlers | 18 | 31 August 2015 | Culture/sensitivity | CDC, Sohar | Six positives for Salmonella |

| 3 | Throat swabs of food handles | 18 | 31 August 2015 | Culture/sensitivity | CDC, Sohar | All negative |

| 4 | Nail swabs food handlers | 18 | 31 August 2015 | Culture/sensitivity | CDC, Sohar/Municipality lab. | One positive for E. coli and coliform |

| 5 | Food raw | 09 | 31 August 2015 | Culture | CDC, Sohar | Uncooked mutton (cut in pieces) unsatisfactory for food |

| 6 | Food cooked and leftover | 08 | 31 August 2015 | Culture | Municipality, Saham | Hummus 1, hummus 2, and vegetable salad positive for Salmonella |

Samples analyzed at local hospital, municipality laboratory and regional CDC

The primary isolates of 36 stool cultures of cases, six food handlers and five food cultures were sent to Central Public Health Laboratory (CPHL) for further confirmation, sub-typing and matching by PFGE method (Table 4).

| No | Sample | Number | Date sent | Test | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Primary isolates of stools cases | 36 | 3 September 15 | Sub-culture | 35 positives for S. Weltevreden serovar |

| 2 | Primary isolates of food handlers | 6 | 17 September 15 | Sub-culture | Six positives for S. Weltevreden |

| 3 | Primary isolates of food samples | 5 | 3 September 15 | Sub-culture | Four positives for S. Weltevreden (vegetable salad, hummus 1, hummus 2, and uncooked pieces of raw meat) |

Results of the primary isolates sent to CPHL, Oman

4. CPHL LABORATORY ANALYSIS

The presence of Salmonella spp. was confirmed in both types of samples (stool of cases, food handlers and food items) received. Almost all stool samples except one were confirmed to have Salmonella spp. Three out of five food samples were also found to have Salmonella spp. No other pathogen was isolated from either stool or food. All the Salmonella spp. strains selected randomly for serotyping were identified as S. Weltevreden (Table 4).

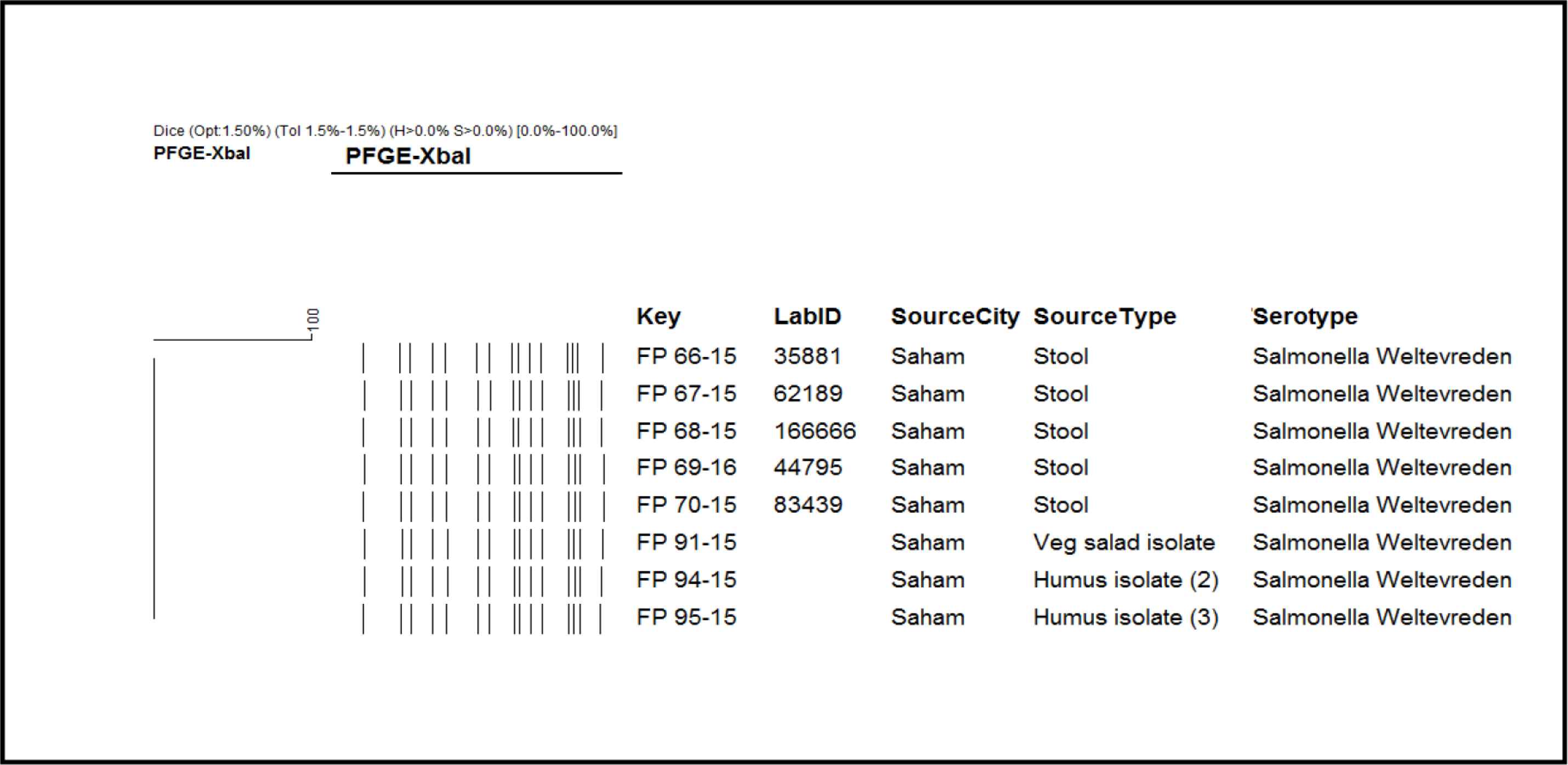

The PFGE gel results showed identical pattern of bands among S. Weltevreden strains isolated from five representative stool isolates and three food isolates belonging to the outbreak (Figure 3). Also, PFGE confirmed genetic relatedness of S. Weltevreden strains from clinical and food isolates to 100%.

Five representative stool isolates and three food isolates have 100% genotypic similarity.

5. DISCUSSION

Up to our knowledge and search, this is the first reported community outbreak of S. Weltevreden in Oman and caused a major public health concern among the local community with the responsible authorities. Investigation of the outbreak reveals 101 confirmed cases with symptoms of gastroenteritis after consuming food from the local restaurant starting from midnight 27 August 2015 and that the causative organism was S. Weltevreden. Immediately after the closure of the restaurant, the cases declined, and no more cases reported which indicate that the restaurant was the source of the outbreak. The laboratory analysis showed the identical pattern of bands among S. Weltevreden strains isolated from the stool and food isolates belonging to the outbreak. As this study has some limitations, testing of chicken was not done which can add important findings on the source of the outbreak. Also, confirmed genetic relatedness of S. Weltevreden strains from clinical and food isolates to 100% for the first time reported in Oman and this has important public health implications.

Worldwide, S. Weltevreden causes less than 4% of the total number of salmonellosis cases in human before 1970 [9]. During the early 1970s, it was the most common serovar to cause human infections in India and the one most frequently isolated from humans in Thailand during the years 1993–2002 [9]. There are several reported cases from India as it is the common cause of gastroenteritis [10–12]. Similar findings have been reported from Malaysia between 1983 and 1992 [13]. Thong et al. [1] found the same subtypes of S. Weltevreden among isolates infecting humans and those in raw vegetables, suggesting that this is a potential reservoir of this serovar in Malaysia. S. Weltevreden was the most common serovar in isolates from seafood, water, and duck in Thailand [8,14]. In a recent study in the United States, S. Weltevreden was the most common serovar found in seafood mainly imported from Thailand and Malaysia [15]. These observations could point to a water-related source for S. Weltevreden.

The results of the outbreak investigation described in this paper suggest that S. Weltevreden is associated with a food-borne outbreak including hummus, chicken, and vegetables from the restaurant as per the specific food attack rate. The laboratory results confirmed that hummus 1, hummus 2, and vegetable salad were positive for S. Weltevreden. However, the possibility of contamination from the unclean vegetable salad cannot be undermined. The most probable reservoir of the S. Weltevreden was the food handlers as the carriers. Those subclinical food handlers were expatriates from Southeast Asia where S. Weltevreden is a common cause of gastroenteritis in Southeast Asia and it can also lead to carrier state [16]. It is estimated that in non-typhoid Salmonellosis 0.5% individuals become chronic carriers shedding bacilli for a long time [17].

The extremely poor personal hygiene of the food handlers, isolation of coliform from the hand swabs, presence of coliform and E. coli tested food, and kitchen tools were a clear indicator of contamination by food handlers. Transmission between food handlers is possible through faeco-oral route which increases the risk of cross-contamination and transmission of organisms from carriers to food and others. The combined and simultaneous effect of food handlers as carriers, contamination and cross-contamination, faulty food processing, keeping, and cooking practices, and favorable ambient environmental factors lead to the outbreak.

This study has several limitations. It was not possible to conduct a case–control study to identify which food item or other specific item was the source of infection or whether the general and multifactor contamination. This was compounded by inadequate information from the cases as most of them discharged from the hospital and was difficult to conduct retrospective interview. Community active surveillance among community was difficult to perform because of large community that is vulnerable to the poisoning.

6. CONCLUSION

An outbreak of S. Weltevreden food poisoning in the Northern part of Sultanate of Oman affected 101 people attending a restaurant in August 2015. Epidemiological and laboratory evidence implicated that food items prepared in the restaurant are responsible for the outbreak of which the most probable source is hummus. However, the role of chicken cannot be ruled out by looking at the proportional attack rate. Multifactors like presence of agent in food handlers, breach in basic hygienic regulation, improper food handling, partial cooking of the food, break of cold chain, and appropriate environmental conditions for the rapid growth of agent in food were added to the outbreak.

After this outbreak, several recommendations are needed to prevent further similar conditions in the future. Strengthening the food safety by regular orientation of the staff on basic hygiene practices must be undertaken and regular stool cultures as screening mechanism to identify carrier state in food handlers to reduce the food handlers induced outbreaks should be emphasized. The intensive monitoring of implementation of food safety regulations is also required.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

AAAM, EEA and VV contributed in writing the manuscript and data analysis. SSAA, IAA and SB contributed in study conceptualization and writing (review and editing) the manuscript. ASAB, AKAJ and AAR were involved in data curation, formal analysis and writing (original draft). Formal analysis, and writing (original draft) the manuscript was carried out by SAA and RK.

FUNDING

No financial support was provided.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Ali A. Al-Maqbali AU - Seif S. Al-Abri AU - V. Vidyanand AU - Idris Al-Abaidani AU - Amal S. Al-Balushi AU - Shyam Bawikar AU - Emadeldin El Amir AU - Saleh Al-Azri AU - Rajesh Kumar AU - Azza Al-Rashdi AU - Amina K. Al-Jardani PY - 2021 DA - 2021/04/09 TI - Community Foodborne of Salmonella Weltevreden Outbreak at Northern Governorate, Sultanate of Oman JO - Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health SP - 224 EP - 229 VL - 11 IS - 2 SN - 2210-6014 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.210404.001 DO - 10.2991/jegh.k.210404.001 ID - Al-Maqbali2021 ER -