Health Insurance: Awareness, Utilization, and its Determinants among the Urban Poor in Delhi, India

- DOI

- 10.2991/j.jegh.2018.09.004How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Health insurance; urban poor; migrants

- Abstract

This study reports the awareness, access, and utilization of health insurance by the urban poor in Delhi, India. The study included 2998 households from 85 urban clusters spread across Delhi. The data were collected through a pretested, interviewer-administered questionnaire. Logistic regression was performed for determinants of health insurance possession. Only 19% knew about health insurance; 18% had health insurance (8% Employees State Insurance Scheme – ESIS – 8% Central Government Health Scheme – CGHS – 1.4%; Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) – 9.4% of the eligible households). In case of health needs, 95% of CGHS, 71% ESIS beneficiaries, and 9.5% of RSBY beneficiaries utilized the schemes for episodic and chronic illnesses. For hospitalization needs, 54% of RSBY, 86% of ESIS, 100% CGHS utilized respective services. Residential area, migration period, possession of ration card, household size, and occupation of the head of the household were significantly associated with possession of RSBY. RSBY played a limited role in meeting the healthcare needs of the people, thus may not be capable of contributing significantly in the efforts of achieving equity in healthcare for the poor. Relatively, ESIS and CGHS served the healthcare needs of the beneficiaries better. Expansion of ESIS to the informal workers may be considered.

HIGHLIGHTS

- •

Urban poor have limited awareness and access to health insurance.

- •

The mandatory health insurance schemes better served the healthcare needs.

- •

RSBY played a limited role in meeting the healthcare needs of the people.

- •

The type of slum, migration duration, and ration card were associated with RSBY enrolment.

- •

- Copyright

- © 2018 Atlantis Press International B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC license (http://creativecommons.org/licences/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

Health planners advocated for the expansion of health insurance as an essential component of India’s healthcare reform and poverty reduction [1,2]. However, enrolment to health insurance in India is very limited. State-run mandatory health insurance schemes, namely, Central Government Health Scheme (CGHS) and Employees State Insurance Scheme (ESIS) are available for working people. Employer-based schemes are offered by public sector organizations such as railways, defence and security forces, mining sectors, and so on by offering medical services and benefits to the employee and his/her dependent family. Private insurance companies offer medical care insurance through individual subscriptions. For those who worked in the informal sector, community-based schemes and government sponsored subsidised schemes are offered. Some NGOs also offer community-based health insurance or micro-insurance schemes. In 2008, the Government of India launched the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY – meaning National Health Insurance Scheme) for below the poverty line families. Some of the abovementioned schemes are briefly described here. CGHS is a mandatory scheme for the central government employees and their dependents and covers all sorts of health-related problems. It provides basic medical services to its beneficiaries through its clinics and dispensaries, and the beneficiaries can access services from the empanelled private hospitals. ESIS, one of the oldest health insurance schemes in India, aims to provide social security for the low-paid workers in the industries and service establishments such as shops, hotels, cinema halls, and so on. Both schemes are contributed by the premiums according to the employee’s payroll, and the other contributors are the employers, central and state governments. In case of ESIS and CGHS, certain expenditures by the beneficiaries for getting healthcare are reimbursed. As a great proportion of the Indian poor workers is in the informal sector, without any social protection, the government of India launched RSBY. The objective of RSBY is to provide financial protection to reduce catastrophic healthcare expenditures/financial liabilities arising out of health shocks that involve hospitalization. A list of illnesses that do not require hospitalization were also covered. Beneficiaries under RSBY are entitled to get healthcare coverage up to Indian Rupees (INR) 30,000 (INR 1 = US$ 0.02). They can also access services from any empanelled private hospital, and it is a cashless transfer scheme. Preexisting conditions are covered, and there is no age limit. Coverage is extended to five members within the family. Beneficiaries pay INR 30 as registration fee, whereas central and state governments pay the premiums [3]. Some private insurance companies such as Reliance, Apollo Munich, Star Health, ICICI Lombard, Max Bupa, and so on, offer health insurance, wherein people have to pay premiums, which vary according to the medical care benefits and conditions of the policy one buys. Some private/corporate hospitals have started health insurance schemes under which the buyer can access healthcare services from that hospital/chain of hospitals, and access is subjected to various predefined conditions. The service varies according to the policy one has bought.

The public health expenditure in India is only 1.04% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Including the private sector contribution, the total health expenditure as a percentage of GDP is estimated at 4%. Of this total expenditure, about 30% is contributed by the public sector [4]. Accessing treatment from private providers leads to high household treatment costs. Healthcare costs are more impoverishing than ever before and almost all hospitalizations, including public hospitals lead to catastrophic health expenditures, and over 63 million people in India face poverty every year due to healthcare costs alone [4]. Moreover, most of the underprivileged and the poor seek care from a variety of private healthcare providers [5], which incurs high treatment costs [6]. This leads to catastrophic healthcare expenditures and impoverishes the low- and middle-income class people. Equity in healthcare emphasized on equal quality of care for all [7,8]. Many countries considered social health insurance as financial mechanism to secure access to adequate healthcare for all at an affordable price [9]. In India, health insurance is seen as one of the options in the absence of government’s initiatives to provide quality and equitable healthcare through public hospitals. In this background, it is important to understand how far these schemes are popular among the people, particularly the poor, and their utilization. Some studies are available on assessing the awareness and utilization of health insurance. Lower levels of awareness (11–30%) and utilization of health insurance were reported from Maharashtra [10,11], whereas higher levels of awareness (64%) were reported from a South Indian population [12]. Thakur from Maharashtra reported that only 29.7% were aware of RSBY, 21.6% were enrolled during 2010–2012 and only 0.3% could utilize the facility for meeting their hospitalization need [10]. Only 11% of the rural population in Maharashtra was aware of health insurance and only 6% actually had any health insurance policy [11]. Studies from other countries also reported lack of awareness of the social health insurance schemes [13,14] and thereby lack of enrollment into the schemes by the eligible [14]. This paper reports the awareness, access, and utilization of health insurance and determinants of possession of health insurance among the urban poor in Delhi, the national capital of India.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was carried out in the National Capital Territory of Delhi, specifically in the socioeconomically disadvantaged urban clusters. Eighty-five urban clusters (34 from resettlement colonies, 33 from older slums, 11 slums without basic amenities, and seven construction site habitations – slum-like habitations), wherein a considerable proportion of newly migrated people live were identified and included in the study. These clusters are spread in 10 of the total 11 districts of Delhi. Resettlement colonies are mainly composed of low socioeconomic groups, and their residence is legal, and the government provides basic amenities to its residents. Several resettlement colonies were set up and sold at subsidized prices by the government to provide relatively better housing/living conditions to its residents, who migrated to Delhi and it made their abode. The residents of resettlement colonies are those who bagged this opportunity and could afford a house in these colonies. However, there are people living in substandard houses in Delhi, though they have migrated long back and still live in slums waiting for acquiring legal status. These slums are referred to as older slums in the present study. Thus, older slums are those that were inhabited by people who migrated to work in the industries and factories long back and started living by establishing their hold in these areas by constructing their own houses. The physical conditions of the older slums are poorer than those of resettlement colonies. Considerable number of houses are pucca i.e., with cemented floor and walls and concrete roofs. Houses were often owned, but the legal ownership of the houses is questionable. These slums are considered for the provision of basic amenities such as water supply and establishing anganwadi (child and mother care centres). The others are slums without any basic amenities, characterized by no sanitation facilities; houses are often katcha (uncemented floors and walls, plastic roof, and used asbestos sheets), and semi-pucca (floor and a part of the walls cemented, the roof is often made up of plastic/asbestos sheets). These houses are often made up of dilapidated materials. People often manage to cement their floors and walls; the roof is often made up of asbestos sheet and plastic covers. Such habitations are often found along the footpaths, railway tracks, and near the bridges. We also included slum-like habitations such as construction site dwellings marked by dwellings that are walled and roofed with tin/asbestos sheets, and these areas are considered as slums without any basic amenities.

The sample size was calculated according to the formula

3. RESULTS

Table 1 presents the study population’s characteristics. A majority of the participants were from slums and were mainly represented by the hierarchically deprived communities (scheduled castes and other backward castes); however, scheduled tribes were less represented. Thus, the study population represents the socioeconomically disadvantaged section. Whereas a majority have migrated and settled in Delhi for more than 10 years-referred to as settled migrants, 18% have migrated to Delhi within the last 10 years in search of livelihood-referred to as recent migrants. The occupation of the head of the household reveals that a majority were working in the informal sector and only 9.5% were working in the formal sector. The monthly incomes indicated that a majority of the present study households were living in poverty.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Residential background | |

| Resettlement colonies | 891 (29.7) |

| Older slums | 1675 (55.9) |

| Slums without basic amenities | 432 (14.4) |

| Type of house | |

| Pucca | 1748 (58.3) |

| Semi-pucca | 944 (31.5) |

| Katcha | 263 (8.8) |

| Temporary/squatter hut | 43 (1.4) |

| Ownership of house | |

| Own | 2297 (76.6) |

| Rented | 399 (13.3) |

| Temporary hut | 302 (10.1) |

| Social class/caste | |

| Scheduled tribe | 28 (0.9) |

| Scheduled caste | 1365 (45.5) |

| Other backward classes | 909 (30.3) |

| Uncategorized | 658 (21.9) |

| Did not/not willing to report | 38 (1.3) |

| Religion | |

| Hindu | 2584 (86.2) |

| Muslim | 366 (12.2) |

| Other than Hindu and Muslim | 48 (1.6) |

| Migration duration | |

| Migrated within the last 10 years | 544 (18.1) |

| Migrated and staying here for more than 10 years | 2454 (81.9) |

| Educational status of the head of the household | |

| No formal schooling | 958 (32.0) |

| 1–5 years of education | 429 (14.3) |

| 6–10 years of education | 1187 (39.6) |

| >10 years of education | 424 (14.1) |

| Occupation of the head of the household | |

| Unskilled worker/daily wage labourer | 1088 (36.3) |

| Skilled worker | 383 (12.8) |

| Small business | 534 (17.8) |

| Temporary salaried job | 668 (22.3) |

| Currently unemployed/not working | 41 (1.4) |

| Employed in government or in organized sector | 284 (9.5) |

| Monthly household income | |

| Up to INR 3000 | 420 (14.0) |

| INR 3001–6000 | 1161 (38.7) |

| INR 6001–9000 | 616 (20.5) |

| INR 9001–12,000 | 342 (11.4) |

| INR > 12,000 | 459 (15.3) |

| Possesses ration card | 1911 (63.7) |

INR, Indian Rupees (INR 1 = US$ 0.02).

Characteristics of the study participants

A majority (98.2%) have heard the term insurance (bima in Hindi-the local language) (Table 2). People were mainly aware of chitfund schemes (92.2%), and life insurance (89%). Other explanations for insurance include, ‘it is like the collection of money and redistribution sort of a thing’ (46.5%); ‘one can borrow money from the self-help group during need’ (37.5%). When asked whether their household or anyone in their household is a member of any such scheme, 24% said membership in some chitfund schemes, 3.3% said life insurance, and 0.3% said they borrowed money from a self-help group. When asked ‘do you think that insurance is something similar to monthly saving?’, 41% replied ‘no.’ 84% of the respondents considered insurance is an amount they pay to get some compensation if something happens. When asked ‘do you think insurance is an amount you pay to get some compensation, but do not get anything if nothing happens?’ a majority answered no (37%) or can’t say (39%). About 41% of the respondents had seen somebody asking to take insurance, whereas 48% knew someone who bought insurance.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Have ever heard of insurance (Bima)? | 2946 (98.3) |

| Heard about chit fund | 2763 (92.2) |

| Heard that payment is received after death of the insured | 2667 (89.0) |

| Heard that hospitalization costs will be given to the insured | 1504 (50.2) |

| It is like collection of money and redistribution sort of thing | 1395 (46.5) |

| Heard that one can borrow money from self-help group during need | 1124 (37.5) |

| Do you think insurance is something similar to monthly saving? | |

| Yes | 807 (26.9) |

| No | 1235 (41.2) |

| No idea | 956 (31.9) |

| Do you think that insurance is an amount you pay to get some compensation if something bad happens? | |

| Yes | 2505 (83.6) |

| No | 135 (4.5) |

| Do not know/cannot say | 358 (11.9) |

| Do you think insurance is an amount you pay to get some compensation, but do not get anything if nothing happens? | |

| Yes | 732 (24.4) |

| No | 1096 (36.6) |

| Do not know | 1170 (39.0) |

| Seen some body asking to take insurance | 1242 (41.4) |

| Knew someone who bought some form of insurance | 1427 (47.6) |

People’s understanding of insurance

Regarding the knowledge of specific insurance schemes, 56% of the respondents do not know about any schemes, 30% knew about life insurance, 19% knew about health insurance (Table 3). It may be mentioned here that this knowledge is low among the recent migrants (9%) compared with settled-migrants (21%) (p < 0.001); and those who were living in slums without basic amenities (13.4%) compared with those of resettlement colonies (p < 0.01) and older slums (20%) (p < 0.05). It may also be mentioned here that those who possess insurance were aware of health insurance. Regarding the possession of health insurance, a majority of the households (82%) were not enrolled into any health insurance scheme. A relatively higher proportion (20%) of the settled migrant households has some form of health insurance compared with the recent migrants (9%). Health insurance possession varied according to the residential background (resettlement colonies – 21%; older slums – 18%; and slums without basic amenities – 14%). Regarding the type of health insurance, 8.5% possess RSBY, 8% possess ESIS, 1.4% possess CGHS, and 0.2% bought private health insurance. The settled migrants (224 out of 254 RSBY beneficiaries) and those who were living in older slums (178 out of 254 beneficiaries) were mainly enrolled into the RSBY scheme. ESIS was available, mainly to settled migrants, and those living in resettlement colonies compared with their counterparts.

| Recent-migrants (n = 544) | Settled-migrants (n = 2454) | Resettlement colonies (n = 891) | Older slums (n = 1675) | Slums without basic amenities | Total (n = 2998) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge about insurance schemes | ||||||

| Do not know about any type of insurance scheme | 352 (64.7) | 1339 (54.6) | 454 (51.0) | 974 (58.1) | 263 (60.9) | 1691 (56.4) |

| Knew about LIC | 156 (28.7) | 738 (30.1) | 296 (33.2) | 469 (28.0) | 129 (29.9) | 894 (29.8) |

| Knew about health insurance | 49 (9.0) | 523 (21.3) | 182 (20.4) | 332 (19.8) | 58 (13.4) | 572 (19.1) |

| Knew about vehicle insurance | 26 (4.8) | 217 (8.8) | 167 (18.7) | 60 (3.6) | 16 (3.7) | 243 (8.1) |

| Knew about other insurances (e.g., house, crop insurance) | 1 (0.2) | 8 (0.3) | 6 (0.7) | 3 (0.2) | 0 | 9 (0.3) |

| Possession of various forms of health insurance | ||||||

| Did not possess | 496 (91.2) | 1957 (79.7) | 701 (78.7) | 1380 (82.4) | 372 (86.1) | 2453 (81.8) |

| Had RSBY | 30 (5.5) | 224 (9.1) | 20 (2.2) | 178 (10.6) | 56 (13.0) | 254 (8.5) |

| Had RSBY among the eligible (n = 2707) | 30 (5.7) | 224 (10.3) | 20 (2.8) | 178 (11.4) | 56 (13.1) | 254 (9.4) |

| Had private health insurance | 0 | 7 (0.3) | 7 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 7 (0.2) |

| Had ESIS | 16 (2.9) | 225 (9.2) | 131 (14.7) | 106 (6.3) | 4 (0.9) | 241 (8.0) |

| Had CGHS | 2 (0.4) | 41 (1.7) | 32 (3.6) | 11 (0.7) | 0 | 43 (1.4) |

| Had some form of health insurance | 48 (8.8) | 497 (20.3) | 190 (21.3) | 295 (17.6) | 60 (13.9) | 545 (18.2) |

Figures in parentheses are percentages; LIC, Life Insurance Corporation of India, a state-owned insurance company; χ2(p) for difference for knowledge of health insurance by migration status = 43.67 (p = 0.0001); χ2(p) for difference for knowledge of health insurance between resettlement colonies and older slums = 0.1332 (0.7152); χ2(p) for difference for knowledge of health insurance between resettlement colonies and slums without basic amenities = 9.6017 (0.0019); χ2(p) for difference for knowledge of health insurance between older slums and slums without basic amenities = 9.3112 (0.0228); χ2(p) for difference for possession of health insurance by migration status = 39.11 (p = 0.00001); χ2(p) for difference for possession of health insurance between resettlement colonies and older slums =5.23 (p = 0.0222); χ2(p) for difference for possession of health insurance between resettlement colonies and slums without basic amenities =10.50 (p = 0.0012); χ2(p) for difference for possession of health insurance between older slums and slums without basic amenities = 3.3978 (p = 0.0653); @ Out of the 2998 households; 2707 households are eligible for RSBY.

Knowledge and possession of various insurance schemes by migration status and residential background

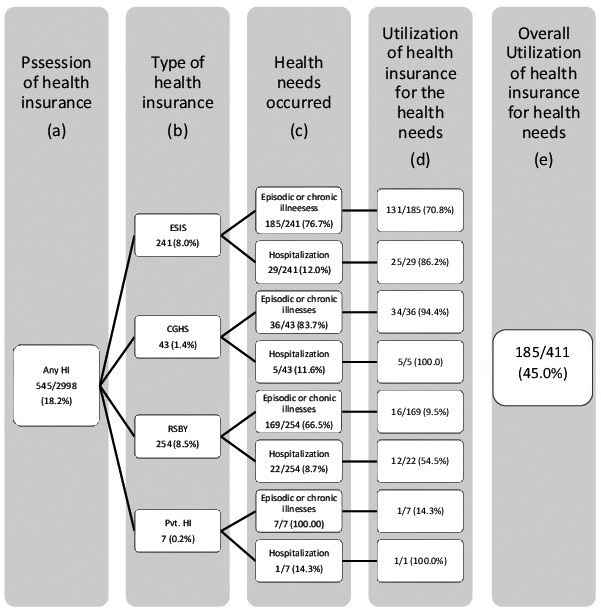

Utilization of healthcare services in case of healthcare need during the past 1 year by type of health insurance has been depicted through Figure 1. The results reveal that 95% of the CGHS beneficiaries and 71% of the ESIS beneficiaries utilized the services for getting treatment for episodic or chronic illnesses compared with 9.5% of RSBY beneficiaries. Whereas 12 out of 22 (54.5%) of the RSBY beneficiaries with the need for hospitalization utilized the services through RSBY during the past year; 86% (24 out of 29) ESIS and 100% (5 out of 5) of CGHS beneficiaries utilized the insurance for meeting the hospitalization needs. When asked whether this insurance helped them get the treatment from a facility of their choice, 46% of CGHS, 24% of ESIS, and 4% of the RSBY beneficiaries said it helped get treatment from a facility of their choice. Those who could not utilize health insurance for healthcare needs were asked for reasons for not utilizing the insurance scheme. The main reasons cited by RSBY beneficiaries with hospitalization needs were that they do not know the use of the card and either misplaced or lost it (6/10) and that they do not know the listed/empanelled hospitals (4/10). ESIS beneficiaries’ reasons for non-utilization include: distance of the ESI hospitals from their home; illness perceived as not serious (for which usually local [unqualified] practitioners are consulted); perception that medicines/treatment available at ESI hospitals are not effective; non-satisfaction; longer queues; and preference for private hospitals.

Utilization of health insurance for the healthcare needs by insurance category. (a) Shows the total number of households possessing some of health insurance. (b) Various types of health insurance possessed by the households. (c) Occurrence of health needs (episodic illness, chronic/long-term illnesses), hospitalization in the past 1 year for any member of the household. (d) Utilization of health insurance as per the health needs. (e) The proportion of households utilized the health insurance when a health need occurred in the household.

It was attempted to find out the determinants of health insurance possession (Table 4). As health insurance is mandatory for those working in the formal sector, we have considered those working in the informal sector and those who were eligible for RSBY. Of the 2998 households, 2707 were eligible for being enrolled into RSBY. Univariate logistic regression did not reveal a significant association of health insurance with caste category, religion, and monthly income. Hence, these variables were not considered for multiple logistic regression. The variables, namely, residential background, migration period, possession of ration card, education attainment of the head of the household, occupation of the head of the household, and household size yielded a p-value of <0.25 during univariate analysis, and were considered for multiple logistic regression. The multiple logistic regression analysis reveals that residential background, migration period, possession of ration card, occupation of the head of the household, and size of the household were significantly associated with enrolment into RSBY. Those living in the slums were more likely to be enrolled into RSBY compared with those living in resettlement colonies. The settled migrants (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 1.945; 95% CI 1.223–3.093) and those households with ration card (AOR 1.993; 95% CI 1.223–2.809) were twice likely to be enrolled. Compared with unskilled workers and daily wage labourers, others revealed fewer chances of being enrolled in the RSBY. Educational attainment of the head of the household did not reveal a significant association.

| Independent variable | Did not possess health insurance, n (%) | Possesses health insurance, n (%) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residential background | |||

| Resettlement colonies | 701 (97.2) | 20 (2.8) | Reference |

| Older slums | 1380 (88.6) | 178 (11.4) | 3.851 (2.372–6.252) |

| Poor slums | 372 (86.9) | 56 (13.1) | 8.052 (4.491–14.436) |

| Migration period | |||

| Recent migrants | 496 (94.3) | 30 (5.7) | Reference |

| Settled migrants | 1957 (89.7) | 224 (10.3) | 1.945 (1.223–3.093) |

| Possession of ration card | |||

| Did not have ration card | 957 (93.5) | 66 (6.5) | Reference |

| Had ration card | 1496 (88.8) | 188 (11.2) | 1.993 (1.414–2.809) |

| Educational attainment of head of the household | |||

| No formal schooling | 803 (88.5) | 104 (11.5) | Reference |

| Up to 5 years of education | 364 (90.3) | 39 (9.7) | 0.870 (0.582–1.300) |

| 6–10 years of education | 978 (92.1) | 84 (7.9) | 0.891 (0.649–1.222) |

| > 10 years of education | 308 (91.9) | 27 (8.1) | 1.254 (0.780–2.015) |

| Occupation of the head of the household | |||

| Unskilled worker/daily wage labourer | 925 (85.0) | 163 (15.0) | Reference |

| Skilled worker | 369 (96.3) | 14 (3.7) | 0.252 (0.143–0.445) |

| Small business | 482 (90.6) | 50 (9.4) | 0.640 (0.453–0.904) |

| Temporary salaried employee | 636 (95.9) | 27 (4.1) | 0.291 (0.189–0.448) |

| Others (not working/unemployed) | 41 (100.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Household size | |||

| Up to 5 members | 1571 (92.1) | 134 (7.9) | Reference |

| > 5 members | 882 (88.0) | 120 (12.0) | 1.392 (1.059–1.830) |

Hosmer and Lemeshow test for goodness of fit, χ2 = 16.116 (p = 0.041). CI, confidence intervals.

Determinants of possession of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY)

4. DISCUSSION

The present study population represents the socioeconomically disadvantaged urban poor. Health insurance was not popular among the urban poor. It may be mentioned here that people were aware of health insurance as they possessed it. Lower levels of awareness were noted among the recent migrants and those who were living in very deprived areas such as slums without any basic amenities. Residential background of the resettlement colony is indicative of relatively better living conditions and employment/work opportunities within the low socioeconomic strata. The RSBY aimed at the poor who worked in the informal sector, and could not make its mark to cover the urban poor as only 9.4% of the households were enrolled. Similar findings were reported from Maharashtra, where only 29.7% were aware about RSBY, 21.6% were enrolled, and only 0.3% could utilize the facility for meeting their hospitalization need [11]. Another study reported that only 11% of the rural population in Maharashtra were aware about health insurance, and only 6% actually had any health insurance policy [12]. However, in a south Indian urban population, 64% were aware of health insurance [11]. Thus, the RSBY scheme is not popular among the poor for whom the scheme was meant. In addition, when the poor are affected mainly by the episodic illnesses and when several of these illnesses are not covered, it renders the scheme uninteresting and non-promising to meet the healthcare needs of the poor. It may be worth mentioning here that from among those with healthcare needs, which do not require hospitalization, only 9.5% could utilize the scheme, and 55% utilized the scheme for hospitalization purposes, whereas the mandatory schemes were relatively better utilized for the health needs. Thus, achieving equity in healthcare through schemes such as RSBY is doubtful due to its limited reach out and its limitation in meeting the healthcare needs of the people. Whitehead et al. [22] opined that one of the main concerns of social health insurance is whether it benefits the disadvantaged is from the equity perspective. Our results reveal that compared with the RSBY, ESIS was better utilized in case of healthcare need. Thus, expanding ESIS to all wage/low-paid workers in the informal sector may be considered in the efforts of achieving equity in healthcare.

Regarding the determinants of enrolment into RSBY schemes, those who were living in slums were more likely to be enrolled in the RSBY, which could be due to the fact that the implementing authorities of the scheme are more likely to approach those living in slums to roll out the scheme. The settled migrants are likely to bag the opportunity due to their familiarity and are more likely to produce necessary documents such as ration card and identity card, whereas recent migrants are not familiar with the various opportunities available in the new sociocultural environment, besides lack of identity. Above all, they are preoccupied with the issues of livelihood opportunities, which was the main reason behind migration [19]. Possession of ration card is indicative of their familiarity with the procedures and networks to bag the existing opportunities. Compared with unskilled/daily wage laborers, others categories of workers such as skilled workers, temporary job holders, and those who were involved in small business had fewer chances of getting enrolled in RSBY. This could be due to the fact that the daily wage workers/unskilled workers (who were poor among all informal workers) were the target group for enrolment, thus the implementing authorities focus on these groups. It was found in this study that some households were enrolled in the RSBY schemes through community visits of the respective government employees/officials rather than being voluntarily enrolled. Dror et al. [23] reported that community-based health insurance was positively associated with household income and education of the head of the household. Education enhances skills and provides employment opportunities. Their chances of getting employment in the formal sector are fair and thus will be covered under mandatory insurance schemes. We could not find any significant association with household income, because we have considered only the RSBY eligible households for regression analysis.

Central Government Health Scheme, ESIS, and employer-based schemes account for 16–18% of all the people in the country, and thus a huge proportion of population is left without any security/social/financial protection in case of health risks. Devadasan and Nagpal [24] suggested expanding the ESIS, which would bring larger numbers and all classes of wage earners into the risk pool. They further thought that this expansion would allow the existing hospitals, facilities, and human resources of ESIS to be better utilized. However, assuring quality and accessibility of services is important. As the beneficiaries of ESIS expressed dissatisfaction, efforts should be made to instil confidence in the service. Nagaraja et al. [25] reported that regular health camps at industries might re-instil confidence among the workers regarding social security systems. Panda et al. [26] suggested that raising awareness is an important prerequisite for voluntary community-based health insurance schemes. Devadasan et al. [27] reported that RSBY had provided partial financial coverage to the poor in Gujarat state and urged for better monitoring of the scheme. Michielsen et al. [28] opined that top-down health insurance schemes do not work fully in the Indian context. Virk and Atun [29] opined that financial protection mechanisms need a balanced approach and evidence-informed policies, which are guided by morbidity and health spending patterns.

There is a need for increasing awareness regarding the existing health insurance schemes for the poor. The poor often suffer from episodic illnesses; and only a limited number of illnesses were covered for treatment under the RSBY. Only a limited number of private hospitals are empanelled to provide services to RSBY beneficiaries. In this background, questions arise whether the schemes such as the RSBY could contribute to the efforts of achieving equity in healthcare. To us it appears that strengthening the government healthcare systems through improving the quality of care and ensuring people-friendly services would be important to meet the healthcare needs of the poor. Sincere effort to address the social determinants is crucial. In a background of a great proportion of the poor working in informal sectors, preference for private healthcare services and perceived quality of government health services, it is necessary to think what system would help the poor to meet its healthcare needs and costs. We opine and agree to the suggestion of expanding ESIS to bring all classes of wage earners to the risk pool [24]. The National Health Policy of India, 2017 opined that all national and state health insurance schemes need to be aligned into a single insurance scheme and a single fund pool reducing fragmentation [4].

5. CONCLUSION

The urban poor have limited access to health insurance with only 18% covered by it, and only 9.4% of the eligible households with access to the RSBY. Awareness of health insurance was found to be low. The mandatory health insurance schemes (ESIS and CGHS) better served the healthcare needs of the beneficiaries as compared with the RSBY. Residential area, migration period, possession of ration card, household size, and occupation of the head of the household were significantly associated with the possession of the RSBY. The RSBY played a limited role in meeting the healthcare needs of the people, thus may not be capable of contributing significantly in the efforts of achieving equity in healthcare for the poor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the support of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi. We thank all the household and community members for their participation and support.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Yadlapalli S. Kusuma AU - Manisha Pal AU - Bontha V. Babu PY - 2018 DA - 2018/12/31 TI - Health Insurance: Awareness, Utilization, and its Determinants among the Urban Poor in Delhi, India JO - Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health SP - 69 EP - 76 VL - 8 IS - 1-2 SN - 2210-6014 UR - https://doi.org/10.2991/j.jegh.2018.09.004 DO - 10.2991/j.jegh.2018.09.004 ID - Kusuma2018 ER -