Establishing a cohort in a developing country: Experiences of the diabetes-tuberculosis treatment outcome cohort study

- DOI

- 10.1016/j.jegh.2017.08.003How to use a DOI?

- Keywords

- Cohort study; Pakistan; Diabetes; Tuberculosis

- Abstract

Background: Prospective cohort studies are instrumental in generating valid scientific evidence based on identifying temporal associations between cause and effect. Researchers in a developing country like Pakistan seldom undertake cohort studies hence little is known about the challenges encountered while conducting them. We describe the retention rates among tuberculosis patients with and without diabetes, look at factors associated with loss to follow up among the cohort and assess operational factors that contributed to retention of cohort.

Methods: A prospective cohort study was initiated in October 2013 at the Gulab Devi Chest Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan. We recruited 614 new adult cases of pulmonary tuberculosis, whose diabetic status was ascertained by conducting random and fasting blood glucose tests. The cohort was followed up at the 2nd, 5th and 6th month while on anti-tuberculosis therapy (ATT) and 6 months after ATT completion to determine treatment outcomes among the two groups i.e. patients with diabetes and patients without diabetes.

Results: The overall retention rate was 81.9% (n = 503), with 82.3% (93/113) among patients with diabetes and 81.8% (410/501) among patients without diabetes (p = 0.91). Age (p = 0.001), area of residence (p = 0.029), marital status (p = 0.001), educational qualification (p = <0.001) and smoking (p = 0.026) were significantly associated with loss to follow up. Respondents were lost to follow up due to inability of research team to contact them as either contact numbers provided were incorrect or switched off (44/111, 39.6%).

Conclusion: We were able to retain 81.9% of PTB patients in the diabetes tuberculosis treatment outcome (DITTO) study for 12 months. Retention rates among people with and without diabetes were similar. Older age, rural residence, illiteracy and smoking were associated with loss to follow up. The study employed gender matched data collectors, had a 24-h helpline for patients and sent follow up reminders through telephone calls rather than short messaging service, which might have contributed to retention of cohort.

- Copyright

- © 2017 Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Cohort studies can be considered the “gold standard” among the observational epidemiological study designs, as they fulfill Hill’s sine qua non criterion of causality by establishing a temporal relationship between cause and effect. But the cohort study design is criticized for long periods of follow up, expense associated with them, large number of study subjects required and issues of attrition [1]. All these issues can be extremely challenging to manage in a developing country like Pakistan, which is already struggling with a myriad of problems. To name a few; allocation of budget for health sector is minimal, health indicators are low in comparison to other Asian countries, the country belongs to the low human development category where 45.6% of the population is multi-dimensionally poor. Approximately half the population is illiterate especially females who enjoy a low status in society with restricted movement affecting their access to health care services [2,3].

The cornerstone of a prospective cohort study is effective follow up of cohort participants, and retaining them for the entire duration of the study, on which relies the success of such studies [4]. However, most epidemiological studies experience issues of loss to follow up which leads to reduced power of the study and a source of bias if it is differential i.e. attrition is related to either the predictor or outcome under study. It is imperative to be aware of factors, which lead to attrition so that appropriate strategies may be adopted to increase retention of cohort participants [5,6] Being less advantaged and having poor health are factors responsible for respondents’ non-participation or loss to follow up [7]. The Danish youth cohort study found drinking and tobacco use to be associated with loss to follow up [8]. A cohort study conducted in Karachi, Pakistan to estimate the incidence rate of HIV among people who inject drugs identified younger age, being homeless, lack of formal education and being incarcerated by law enforcement agencies as predictors of loss to follow up [9].

Pakistan has a high burden of TB, with an estimated incidence of 270 cases per 100,000 population in addition to its expanding population of diabetics, with a national prevalence of 6.9% [10,11]. Diabetes mellitus has detrimental effect on TB treatment outcomes such as: increased chances of relapse, failure, default and death among co-infected patients [12,13]. Hence the diabetes-tuberculosis treatment outcome (DITTO) study; a prospective cohort study was undertaken in Pakistan to assess tuberculosis treatment outcome among diabetic patients. We are aware that the results of a cohort study are a big threat to its validity if the loss to follow up is more than 20%. The participants who are lost to follow up are often seen to have a different prognosis than those who remain a part of the cohort [14]. Researchers in a developing country like Pakistan seldom undertake cohort studies, which explains the dearth of information on retention and tracking strategies employed, and challenges encountered in such studies. It has been established that diabetes is a determinant of loss to follow up among patients undergoing treatment for tuberculosis [15]. This may be attributed to financial constraints and high pill burden, which hinders the co-infected patients arrival at health facility for follow up visits [16]. Our primary objective was to describe the retention rates among tuberculosis patients with and without diabetes and secondary objectives were to look at factors associated with loss to follow up among the cohort and assess operational factors that contributed to retention of cohort.

2. Materials & methods

Details of this prospective longitudinal study have been previously published [17]. In brief, a prospective cohort study was undertaken at the Gulab Devi Chest Hospital (GDH), a tertiary care hospital in Lahore, Pakistan. GDH is one of the oldest cardiothoracic hospitals in South Asia, which was established in 1934. It is a 1500 bed hospital, which provides free diagnostic and treatment services to TB patients of all socioeconomic backgrounds, from all over the country.

The cohort of 614 PTB patients was recruited between October 2013 and March 2014 from the outpatient department of GDH. PTB patients who were diagnosed, registered and obtained treatment at GDH were enrolled in the study if they fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were willing to participate. The inclusion criteria comprised of: a new adult (≥15 years of age) pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) patient, both sputum smear positive and negative who had never taken TB drugs in the past or had taken them for less than 4 weeks, was registered with GDH for his/her anti-tuberculosis treatment, consented to participate and could provide his/her contact details. Patients were requested to provide home addresses and two telephone numbers (landline or mobile) belonging either to them, a family member or neighbour to facilitate the follow up process. The diagnosis of PTB, both sputum smear positive and sputum smear negative was made according to the definition given by the National Tuberculosis Control Program (NTP) [18]. According to NTP a new case was a PTB patient who had never taken ATT in the past or had taken it for less than 4 weeks and had not registered with NTP. In order to establish a new case, patients’ self-report regarding past history of tuberculosis was initiated.

The diabetic status of patients was ascertained. People with diabetes gave a self-history of the disease, which was verified by inquiring about the hypoglycaemic drugs that they were consuming. They were included in the study as patients with known diabetes. All others were tested for diabetes through random blood glucose (RBG) test at the time of enrollment. Patients with RBG value ≥110 mg/dl were tested through the fasting blood glucose (FBG) test at the first follow up visit. Patients having a FBG ≥126 mg/dl were labeled as patients with diabetes. Based on the result of FBG test patients were divided into two groups, those exposed i.e. patients with diabetes and those unexposed i.e. patients without diabetes. Both groups were followed up prospectively at 2nd, 5th and 6th month while on ATT and 6 months after completion of ATT in order to compare the treatment outcomes in the exposed and the unexposed groups. Follow up was completed in March 2015. The treatment outcome definitions provided by the NTP and WHO were adhered to in the study [18,19]. Treatment outcomes observed included: cured, treatment completed, treatment failure, defaulted, transferred out, patients who died during the ATT, and those who relapsed. Two full time data collectors, both male and female were hired for data collection. The sources of data included a pretested patient questionnaire which comprised of questions on patients socio-demographics, lifestyle and behavioural characteristics, history of co-morbidity, clinical presentation of tuberculosis, sputum smear microscopy for assessment of treatment outcomes, blood tests for estimation of glycosylated hemoglobin of patients with diabetes and anthropometric examination for assessment of body mass index. The known and newly diagnosed diabetes patients were referred to a specialist for free management of their diabetes.

Efforts were made to minimize loss to follow up. Reminder telephone calls were made a week before scheduled appointment. Approximately 10–20 telephone calls were made till contact with participant was established. At each visit, participants contact details were reviewed and participants were given the date of their subsequent appointment, on their Patient Identification Card. Additionally, participants were provided with Rs.100 (US $0.95) as compensation for the time provided to the study. The PTB patients who were lost to follow up were contacted through telephone calls to ascertain the reasons for their loss from the cohort.

The data thus collected were entered and analyzed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 16. We undertook a descriptive analysis whereby we calculated: 1) the number and proportion of persons with selected demographic and social characteristics at baseline; 2) the number and proportion of persons lost to follow up at each of the follow up visits according to their diabetic status and 3) the number and proportion of factors identified by respondents for loss to follow up. We then determined the association between age group, gender, area of residence, educational qualification, marital status, history of smoking and diabetic status with loss to follow up using Chi-square statistics significant at a p-value of ≤0.05.

Patients were explained the purpose of the study and schedule of follow-up visits. Written informed consent was obtained from eligible patients volunteering to participate in the study. The illiterate patients requested the data collectors to give them a verbal overview of the consent form. Ethical approval was sought from the Institutional Ethical Review Committee (IERC) of Health Services Academy, Islamabad before initiating the study, which was duly granted. Permission was also taken from the administration of the Gulab Devi Chest Hospital, Lahore where data collection was undertaken.

3. Results

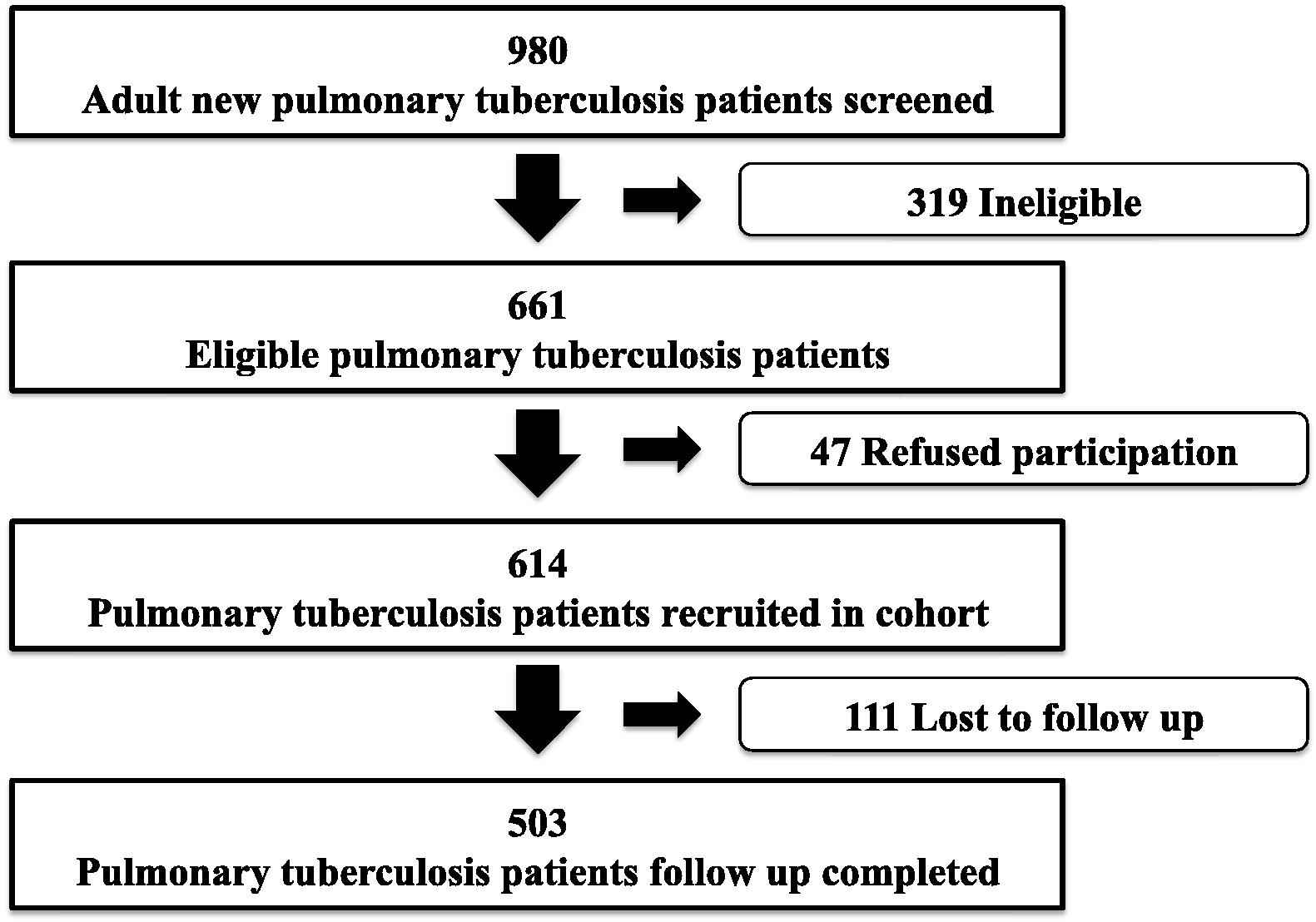

We identified 980 new cases of adult PTB, of which 661 (661/980, 67%) fulfilled the eligibility criteria of the study, 614 (614/661, 92.8%) were recruited in the cohort and 503 PTB patients completed follow up (503/614, 81.9%). (Fig. 1). Of the 319 ineligible patients, 115 (36%) were unable to recall their own/relatives’/neighbours’ telephone numbers, 33 (10%) were unable to provide complete address (home/relatives/neighbourhood), 25 (8%) did not possess a mobile telephone neither had access to a landline, 124 (39%) did not get registered at Gulab Devi Chest Hospital for treatment and 22 (7%) patients were unsure of their previous ATT intake.

Diabetes tuberculosis treatment outcome study’s flow chart of recruitment and follow up.

The socio-demographic profile of 614 recruited members of the cohort is displayed in Table 1. The mean age of the cohort members in this study was found to be 32 ± 15 years. The assessment of respondents’ diabetic status revealed that 113(18.4%) had diabetes. Of the patients with diabetes in the PTB cohort, 85(75%) were patients with known diabetes and 28(25%) were patients with newly diagnosed diabetes. The overall follow up completion rate of the 614 PTB patients in the DITTO study was 81.9% (503), with an approximately equal proportion among diabetics 82.3% (93/113) and non-diabetics 81.8% (410/501). (p = 0.91)

| Characteristic | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age Group (in years) | ||

| 15–19 | 135 | 22.0 |

| 20–24 | 142 | 23.1 |

| 25–29 | 67 | 10.9 |

| 30–39 | 90 | 14.7 |

| 40–49 | 67 | 10.9 |

| >50 | 113 | 18.4 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 312 | 50.8 |

| Female | 302 | 49.2 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 424 | 69.1 |

| Rural | 190 | 30.9 |

| Educational qualification | ||

| Illiterate | 323 | 52.6 |

| Primary | 84 | 13.7 |

| Matriculation | 146 | 23.8 |

| Intermediate | 30 | 4.9 |

| Bachelors | 18 | 2.9 |

| Masters and above | 13 | 2.1 |

| Income Category (Rupees) | ||

| Nil‡ | 384 | 62.5 |

| <5000 | 43 | 7.0 |

| 5100–8000 | 67 | 10.9 |

| 8100–11000 | 54 | 8.8 |

| 11100–14000 | 26 | 4.2 |

| 14100–17000 | 21 | 3.4 |

| >17100 | 19 | 3.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 344 | 56.0 |

| Single | 267 | 43.5 |

| Divorced | 1 | 0.2 |

| Widowed | 2 | 0.3 |

| Total | 614 | 100 |

Income in the form of loans/help from relatives/extended family.

Socio-demographic profile of 614 new pulmonary tuberculosis patients recruited at Gulab Devi Chest Hospital, Lahore between October 2013 and March 2014 (n = 614).

The loss to follow up rates among PTB patients with diabetes and PTB patients without diabetes at each follow up are displayed in Table 2. The total loss to follow up among PTB patients with diabetes and PTB patients without diabetes was 18% (20/113) and 18% (91/501) respectively (p = 0.907).

| Known Diabetics | Diabetic status to be confirmed# | Non-diabetic¶ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Follow Up | |||

| Number of PTB patients in cohort | 85 | 113 | 416 |

| Number of PTB patients experienced TO* | 7 | 3 | 6 |

| Number of PTB patients lost to follow up | 8 | 7 | 25 |

| Loss to follow up (%) | 8/85, 9% | 7/113, 6% | 25/416, 6% |

| Diabetic | Non-diabetic | ||

| 2nd Follow Up | |||

| Number of PTB patients in cohort | 98† | 460 | |

| Number of PTB patients experienced TO* | 7 | 24 | |

| Number of PTB patients lost to follow up | 4 | 33 | |

| Loss to follow up (%) | 4/98, 4% | 33/460, 7% | |

| 3rd Follow Up | |||

| Number of PTB patients in cohort | 87 | 403 | |

| Number of PTB patients experienced TO* | 0 | 7 | |

| Number of PTB patients lost to follow up | 8 | 26 | |

| Loss to follow up (%) | 8/87, 9% | 26/403, 6% | |

| 4th Follow Up | |||

| Number of PTB patients in cohort | 79 | 370 | |

| Number of PTB patients experienced TO* | 9 | 6 | |

| Number of PTB patients lost to follow up | 0 | 0 | |

| Loss to follow up (%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Total Loss to follow up (%) | 20/113, 18% | 91/501, 18% | |

Treatment outcome includes: cured, treatment completed, treatment failure, defaulted, transferred out, patients who died during the ATT, and those who relapsed.

Patients having a RBG >110 mg/dl, who underwent FBG test at 2nd follow up.

Patients having a RBG ≤110 mg/dl.

70 Known diabetics + 28 newly diagnosed diabetics.

Distribution of pulmonary tuberculosis patients that were lost to follow up between four follow ups according to diabetic status from October 2013 to March 2015 at Gulab Devi Chest Hospital, Lahore.

Age (p = 0.001), area of residence (p = 0.029), being a smoker (p = 0.026) and marital status of the respondent (p = 0.001) were significantly associated with loss to follow up. (Table 3)

| PTB patients retained in cohort n = 503 |

PTB patients lost to follow-up n = 111 |

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age Group (in years) | 0.001* | ||||

| 15–19 | 119 | 88 | 16 | 12 | |

| 20–24 | 128 | 90 | 14 | 10 | |

| 25–29 | 50 | 75 | 17 | 25 | |

| 30–39 | 72 | 80 | 18 | 20 | |

| 40–49 | 53 | 79 | 14 | 21 | |

| >50 | 81 | 72 | 32 | 28 | |

| Gender | 0.335 | ||||

| Male | 251 | 80 | 61 | 20 | |

| Female | 252 | 83 | 50 | 17 | |

| Residence | 0.029* | ||||

| Urban | 357 | 84 | 67 | 16 | |

| Rural | 146 | 77 | 44 | 23 | |

| Educational qualification | <0.001* | ||||

| Illiterate | 243 | 75 | 80 | 25 | |

| Primary | 74 | 88 | 10 | 12 | |

| Matriculation | 129 | 88 | 17 | 12 | |

| Intermediate | 27 | 90 | 3 | 10 | |

| Bachelors | 18 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Masters and above | 12 | 92 | 1 | 8 | |

| Marital status | 0.001* | ||||

| Married | 264 | 77 | 80 | 23 | |

| Single | 237 | 89 | 30 | 11 | |

| Divorced | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Widowed | 1 | 50 | 1 | 50 | |

| Smoker | 0.026* | ||||

| Yes | 78 | 74 | 27 | 26 | |

| No | 425 | 83.5 | 84 | 16.5 | |

| Diabetic | 0.907 | ||||

| Yes | 93 | 82 | 20 | 18 | |

| No | 410 | 82 | 91 | 18 | |

Factors associated with loss to follow up among new pulmonary tuberculosis patients followed up at 12 months for treatment outcome at Gulab Devi Chest Hospital, Lahore.

As is highlighted in table 4, the major reason for loss to follow up among the respondents were unknown because of inability to contact them due to incorrect contact numbers provided to the research team and contact numbers being switched off (44/111, 39.6%). Three patients reported terminating ATT and initiating medicines for psychiatric illness (3/111, 2.7%) or switching to homeopathic medicines (4/111, 3.6%).

| Reasons | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Unknown* | 44 (39.6) |

| Refusal/denial of phone call recipients to the existence of a TB patient in the household | 20 (18.0) |

| Patients’ movement from a relatives’ house in the city where the hospital was located to their own residence in a village | 13 (11.7) |

| Patients found TB drugs very strong, hence stopped having them | 10 (9.0) |

| Patient had shifted to a private clinic for their treatment | 7 (6.3) |

| Patient considered ATT ineffective, hence discontinued it | 5 (4.5) |

| Patients proclaimed they don’t have TB, rather are under the influence of evil spell | 5 (4.5) |

| Patients had terminated ATT because they considered homeopathic medicine more effective | 4 (3.6) |

| Stopped ATT and started medicines for psychiatric illness | 3 (2.7) |

The contact numbers provided at recruitment to the researchers were incorrect/inaccessible and mobile phones were switched off, ATT = anti-tuberculosis therapy.

Reasons for loss to follow up among 111 PTB patients comprising diabetes tuberculosis treatment outcome cohort study undertaken at Gulab Devi Chest Hospital, Lahore.

4. Discussion

The follow up completion rate of the study was 81.9%, which cannot be compared to similar studies in the country for lack of such a venture undertaken in the past i.e. a prospective cohort study to look at treatment outcome among tuberculosis patients with and without diabetes. However, a prospective cohort study undertaken in Karachi to identify predictors of gestational diabetes among 750 pregnant women reported 18.5% respondents were lost to follow up; results compatible to our study [20]. A higher loss to follow up rate of 25.5% was reported by another cohort study undertaken in Karachi on 636 people who inject drugs (PWID). The threshold for follow up has been recommended to be 60–80% in cohort studies [21].

The DITTO study identified factors associated with loss to follow up among the PTB cohort. We found residing in rural area, age above 50 years, being married, smoking and illiteracy to be significantly associated with loss to follow up. Lack of formal education and smoking has been reported as predictors of loss to follow up by other studies [8,9] Elderly cohort members have a greater probability of being lost from the cohort due to social and health issues [22]. Elderly patients may also be lost to follow up as they may have died. The majority of patients were lost to follow up due to inability of research team to contact them as either contact numbers provided were incorrect or switched off. Non-contact and refusal to participate in a study are established factors of attrition from a longitudinal study. [23]. One of the mainstays of a cohort study is follow up of cohort members to determine the development of outcome. To ensure a robust follow up it is imperative to have detailed contact information of the recruits [24]. Therefore, the DITTO study refreshed the contact information of members at each follow-up visit. We ensured that patients registered at the Gulab Devi hospital were recruited only; as proximity of health facility from home was one of the criteria, which needed to be fulfilled to be registered, hence facilitating follow up. Another strategy to ensure patient turnout was; thoroughly explaining the follow up schedule to respondents at recruitment and scheduling their visits to coincide with patients’ drug collection time from hospital. Additionally, a lot of effort is required to maintain the cohort and maximize patient follow up. One approach is to give incentives for participation [25]. Our study also compensated patient for their time and effort through a nominal amount, which was given to them at the first follow up visit. This may have contributed to an increase in retention of the participants. A cohort study in Karachi gave money and gifts such as hospital monogrammed towels, biscuits and baby products in recognition of time and effort provided to the study [26]. A cohort study in Pomerania provided their study subjects with either travel allowance back and forth from the health facility or some expense allowance in an attempt to increase response rate [27].

The DITTO study experienced various challenges during the study period. At the time of recruitment, it was required to elicit previous ATT intake of patient as poor treatment outcomes have been observed in individuals’ having consumed ATT in the past [28]. Many respondents were not sure of their previous history of ATT intake, hence couldn’t be recruited as they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria of the study. This lack of awareness regarding their previous disease status may be attributed to their low level of literacy [29]. Additionally, some patients did not participate due to shortage of time. Long waiting times at each visit for the study hindering working women’s enrollment has been identified by other researchers as well [30].

The study used a consent form translated in local language, which was read out to those who were unable to read. In another US cohort, during the recruitment phase the consent form was also read out to individuals with a low level of literacy [24]. The study found respondents were not willing to sign the consent forms but were willing to participate in the study after giving verbal consent. The signing of a document threatened them and made them feel insecure and suspicious. Literature has highlighted various reasons for refusal to consent for participation [31]. A study conducted in Qatar found similar results and the researchers were also of the view that written consent maybe substituted with verbal consent in a culture like ours where signing documents is avoided by individuals [32]. Other research has indicated that some Western concepts of informed consent are at variance with those in developing countries [33].

The data collection was carried out in the outpatient department of the hospital, where patients and their accompanying family members could not be separated. The young female patients in the study, who were either recently married or engaged did not want their TB status disclosed to the accompanying person because of the taboo associated with the disease and fear of divorce/engagement breaking on discovery of her disease status [34]. In comparison to most prospective longitudinal studies with long follow up periods and the fear of a high attrition, the DITTO study had a short follow up period of twelve months [35]. But despite the short length of follow up, DITTO study employed various methods to maintain the cohort ensuring low attrition and effective follow up of the patients. Considering the prevailing cultural environment, both a male and a female data collector were hired and trained for gender matched data collection. We ensured negligible data collector turnover, which helped develop a good rapport between the researcher and respondents. Additionally, we provided a 24-h helpline, which was very popular among the patients, was greatly appreciated by them and helped develop sustained relationships with them; thereby enhancing the response rate. The initial protocol of DITTO study mentioned the use of short messaging service (SMS) to remind patients of their follow up visits. However, as we proceeded with the study it was noted that patients did not respond to SMS reminders. They didn’t turn up for their follow up visits after being sent a SMS reminder. Therefore, telephone calls were used to remind patients of their time of visit to the health facility. Many telephonic reminders were given to the cohort members, to ensure they turned up at the health facility. A cohort study by Russell et al. also reported making innumerable calls to locate respondents, which although effective was found to be costly and labour-intensive [36]. Our study has a few limitations. Strategies employed here may not prove to be beneficial in all settings. We were not able to quantify if only incentives played an important part in retention of patients. It is likely that the combination of strategies used here contributed to enhance retention. Future studies utilizing experimental design may be able to delineate the individual or combined effect of these interventions on retention of participants in cohorts.

5. Conclusion

The DITTO study demonstrated an ability to retain more than 80% of participants for 12 months. Retention rates among people with and without diabetes were similar. Our study identified rural residence, older age, being married, smoking and illiteracy as significant predictors of loss to follow-up. Gender matched data collectors, 24-h helpline for patients and follow up reminders through telephone calls rather than short messaging service, might have contributed to retention of cohort and could be used by other researchers.

Conflict of interest

None.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jegh.2017.08.003.

References

Cite this article

TY - JOUR AU - Fatima Mukhtar AU - Zahid A. Butt PY - 2017 DA - 2017/08/24 TI - Establishing a cohort in a developing country: Experiences of the diabetes-tuberculosis treatment outcome cohort study JO - Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health SP - 249 EP - 254 VL - 7 IS - 4 SN - 2210-6014 UR - https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jegh.2017.08.003 DO - 10.1016/j.jegh.2017.08.003 ID - Mukhtar2017 ER -